When my pal Dr McClain yanked me out of retirement and asked me to pen a quick post on all the hubbub around the televised and much discussed close encounter between world-champion surfer Mick Fanning and a presumed great white shark at the start of the J-Bay Open in South Africa last weekend, I was given no particular reason for his dusting me off as author. Perhaps Craig’s intentions were to approach someone whom he knows is working on shark conservation at the moment to provide a voice on the subject. Or maybe he intended for me to make some sort of connection to shark-human interactions since I spend a lot of my time thinking about this in my work. Or maybe his intention was for me to employ my trademark wise-assery and irreverent commentary on all the bloviating that’s been done since the event.Here’s the thing about intention… How do we know for sure what anyone (let alone a shark) intends?

Thus far I’ve seen narratives surrounding the Fanning event fall into two distinct themes, hinging on whether or not you wish to call this event a “shark attack.” Within the shark attack camp, I’m seeing lots of “”Fanning got lucky,” or “The shark missed,” story lines. Taking this to the absurd and crackpot level, the always reliable Fox News has even begun to make calls that maybe it’s time to “rid the ocean of sharks.”

On the other end of the spectrum are those who perhaps justifiably feel that the words “shark attack,” are prejudicial and loaded (in other words weighted towards an interpretation where the shark has targeted a human with the intent of harm (the consumption of the human being one possible outcome). This language revision camp has been employing a lot of their own “just so stories” that suggest the “shark got tangled in the surf leash,” or the shark was just “curious.” To this reader, a lot of this smacks of apologetics (and to be fair, I realize that sharks have an unfair and undeserved reputation that words like “attack” help to promote).

Any or all of these explanations might sound plausible and could be correct. But unless someone has suddenly discovered the ability to mind-meld via television with a great white shark, how are any of us to know what was the intention of the shark?

So what do we know about the Fanning incident? We know the time of year, day and hour the incident occurred. We probably have some physical/oceanographic data (water temperature, tidal state, meteorological conditions, etc). We know what Fanning was wearing (color, patterns) and the color and shape of his board. We know that particular stretch of South Africa is home to a lot of seals, and a lot of seal predators. And we seem to know (or presume) that the shark in the video of the incident was a great white shark (there have even been some preliminary back-of-the-envelope calculations of size of the shark).

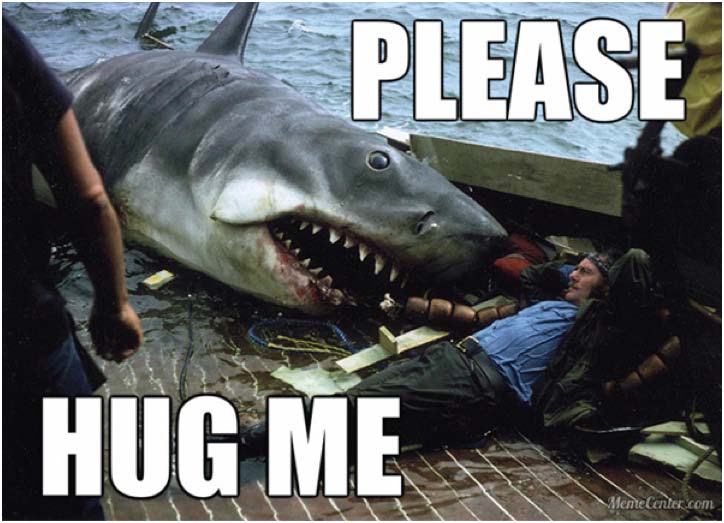

As far as the intention of the shark, I can offer no compelling accounting that doesn’t load hints to my personal agenda or Panglossian spin. Was the shark targeting the surfer or board for an exploratory bite and Fanning got lucky? Was the shark planning a bite and got distracted after getting tangled in the leash? Was the shark just curious and got spooked by the leash or Fanning’s movements? Did the shark seek out Fanning in search of hugs, and then—after a punch from the surf champion—add more salty tears to an already full ocean?

Well for sure, science gives us some pretty useful approaches to begin to get to the bottom of animal intent. We can (and do) systematically study sharks and are beginning to get a good sense of their behavior. For many species, we are able to document prey as well as behavior around prey. As we spend more and more time in close proximity to sharks, we are learning that they (even those species on many of Shark Week’s “Most Dangerous Sharks” lists) don’t seem to regard us as food when we are in their company. I’ve personally been inches from hundreds of bull sharks on numerous dives and have lived to type out this post with all 10 fingers.

On the one hand, I’m not a fan of language policing. I think it’s hard to define in practical, every-day usage a way to describe a human-shark interaction that results in blood-loss or bodily injury as NOT an attack. I say this in full recognition that the blood-loss or bodily injury may have been an accident or the shark may have “mistaken” a human for something else (whatever that unpacks to mean). In the Fanning incident, maybe the shark was trying to explore Fanning’s board or body as food. If it did, and Fanning were injured, maybe it would leave the scene convinced it was the “wrong” food. Maybe not. But as my friend and colleague WWF-Pacific’s Sharks Manager, Ian Campbell, recently commented, “Sharks do attack people. Doesn’t mean that their populations aren’t in trouble.”

When I personally see all the “don’t say attack” rhetoric being used, I wonder what we should be calling those incidents when dogs or grizzly bears have unfortunate run-ins with humans. In the case of bears, while we’ve comparably decimated their populations and restricted their range, we still seem to be able to co-exist without language policing.

Which makes me consider the other hand, my policy and conservation-focused hand, that words have power and influence. As researchers Chris Neff and Robert Hueter have correctly noted, “Few phrases in the Western world evoke as much emotion or as powerful an image as the words “shark” and “attack.” We have a visceral reaction to each word. Together they conjure our worst nightmares. But globally, sharks are in trouble. Estimates suggest 100 million sharks die each year from fishing alone. This may be twice as fast as shark’s ability to replenish their numbers. Getting people to care about the conservation of sharks hinges on their ability to care about sharks. The legacy of Jaws is not helping in this regard. The science we are amassing is painting an altogether different picture of shark behavior than what has been culturally ingrained my Hollywood. They are not mindless killing machines, but graceful, intelligent predators. If some judicious word policing can help in steering public perceptions and attitudes towards conservation, how bad can that be?

And as to the shark alarmist trend that seems to occupy a lot of public bandwidth (and Fox News) these days, maybe we can look to the grizzly bear once again. When we enter bear country, we take precautions. The chance of a bad human-bear outcome is very low, but there is a risk. When we choose to explore habitat shared by grizzlies, we might wear bells, sing, clap, or even carry pepper spray. In extreme situations, guns might be appropriate. We haven’t demonized grizzlies (or at least we don’t anymore). But we recognize that we are entering an ecosystem that may not have us as the toughest organism around. Want to be 100% risk free? Don’t enter bear country. Perhaps we can apply some of this common sense to our relationship with the ocean as well, and let’s just let sharks be sharks.

Share the post "The Tension of Intention: A Surfer, A Shark, A Fox, And A Grizzly"

I think that a lot of important things are said in this article, and I appreciate that. It’s a balanced approach to the “call it attack” vs. “don’t call it attack” debate.

One thing looms heavily in the air for me: the discussion of the article presupposes the debate around an actual shark bite incident, where a person suffers harm. That’s a relevant debate.

What do we do here, though? Mick Fanning did not sustain a physical injury, and as much as we can’t really read the intent of a shark that bites someone, we can even less suppose the intent of a shark that didn’t bite anyone. It would be as valid to wonder what would have happened if Fanning were five feet in shore, or something to that effect. That’s touched on in this article, but I still think it’s a different debate. I don’t see a world where it’s really appropriate to call this specific situation an attack, if only because – intent aside – no one was attacked (emphasis!). No one sustained a physical injury.

Rick, this is just fucking brilliant, fully agree.

Well said!