You will never see the Ninja Lanternshark coming, not because it’s dark and elusive, but because you won’t be swimming below 1,000 feet deep off the coast of Central America any time soon.

Discoveries in science are not often the result of the stereotypical and unrealistic step-by-step scientific method, but usually occur through other more mundane and unexpected routes. Think of Flemming’s moldy lunchbox sandwiches as the pathway to developing penicillin, or Newton stone-drunk in an orchard contemplating gravity with a rain of apples falling on his noggin’. When marine biologists discover a new species, especially a new shark species, it isn’t the result of putting on a red-knit cap and a pair of Speedos on your research vessel and loudly declaring that you are going to discover a new shark. Throw the mini-sub overboard, gaze into the darkness through an oval window, and bam – a new species is discovered. Bottles of Clicquot pop back on deck, the scientific community hoists you on their shoulders and applauds your excellence in zoology. Maybe the jackals from Shark Week give you a call to recreate your daring feats for a documentary low on facts and ripe with pseudoscience, likely replacing you with younger C-list actors and warping what actually happened with their own overly-dramatic narrative. With our discovery of the newly-described Ninja Lanernshark, it wasn’t the reward of a planned grand adventure, but was the usual meander of social connections, cooperation among colleagues, the benefits of museum archives, hard work from unpaid graduate students, and plain old good luck.

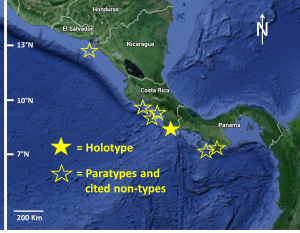

Several years back, John McCosker of the California Academy of Sciences and Dave Ebert, also a Cal. Academy research associate like myself, and I were studying chimeras, distant deep-sea cousins of sharks. One day I got an email from D. Ross Robertson of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who in 2010 chartered a Spanish trawler and conducted a number of deep-sea collections off the Pacific coast of Central America, and among the barrels of specimens he collected were a few odd-looking chimeras he wanted us to identify. Ross had the good sense to photograph many of these specimens while they were still fresh out of the nets, and he forwarded them to us. Along with the photos of these chimeras were hundreds of other photos of deep-sea fishes, including sharks, skates, and bony fishes that were either entirely unknown species, or new locality records for previously-known but poorly documented species. To a deep-sea ichthyologist, this was the jackpot. I soon headed to the ichthyology collections at the Smithsonian and spent several days pulling these specimens out of gallon jars of ethanol or dipping my arms nearly shoulder-deep into huge vats of the stuff where the large specimens were preserved. Taking photographs, measurements, and making on-the-spot identifications, I compiled a large number of specimens that the fine folks in the Smithsonian ichthyology department shipped back to the California Academy of Sciences where we could more closely study them.

Several years back, John McCosker of the California Academy of Sciences and Dave Ebert, also a Cal. Academy research associate like myself, and I were studying chimeras, distant deep-sea cousins of sharks. One day I got an email from D. Ross Robertson of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who in 2010 chartered a Spanish trawler and conducted a number of deep-sea collections off the Pacific coast of Central America, and among the barrels of specimens he collected were a few odd-looking chimeras he wanted us to identify. Ross had the good sense to photograph many of these specimens while they were still fresh out of the nets, and he forwarded them to us. Along with the photos of these chimeras were hundreds of other photos of deep-sea fishes, including sharks, skates, and bony fishes that were either entirely unknown species, or new locality records for previously-known but poorly documented species. To a deep-sea ichthyologist, this was the jackpot. I soon headed to the ichthyology collections at the Smithsonian and spent several days pulling these specimens out of gallon jars of ethanol or dipping my arms nearly shoulder-deep into huge vats of the stuff where the large specimens were preserved. Taking photographs, measurements, and making on-the-spot identifications, I compiled a large number of specimens that the fine folks in the Smithsonian ichthyology department shipped back to the California Academy of Sciences where we could more closely study them.

Once the sharks arrived, Dave and I looked them over and we both thought they were a new species since

they were unlike anything yet known from the eastern central Pacific, but “discovering” a new species isn’t as easy as that. To describe a new species you need to conclusively show the range of variation in your new species is outside the range of variation in previously-known species. It has to be significantly different than any relative species thus far known. To do this required the painstaking and time consuming process of morphometrics, the detailed series of measurements of the sharks anatomy, and meristics, the count of such things as vertebrae, tooth rows, number of dermal denticles, etc. Fortunately, Dave and I already had a process where we worked with young go-getters, mainly his graduate students at the Pacific Shark Research Center in the Moss Landing Marine Laboratory, to learn the process of describing and publishing new species of sharks, rays, and chimeras. Victoria Vasquez was one of his students already with experience in shark ecology and conservation outreach, so he assigned her to heading the job of the not-so-sexy nitty-gritty of the detailed analysis of the formalin-preserved shark specimens with microscopes, rulers, and dial calipers, and she was a superstar at it.

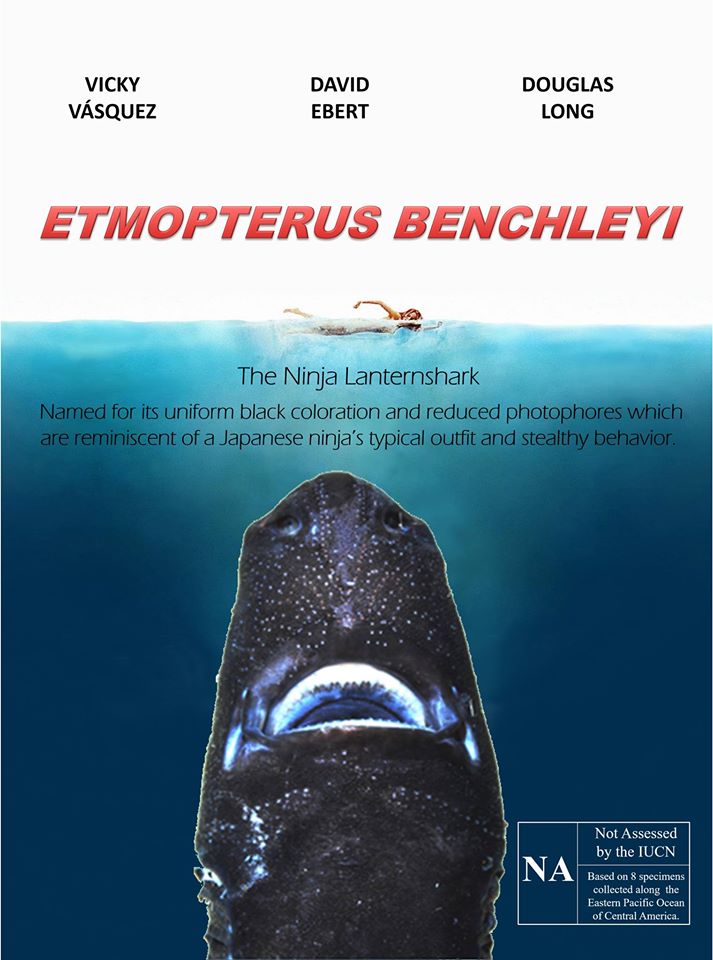

It soon became clear that these small sharks did indeed represent a new species of lanternshark, a family of deep-sea sharks with this as the first species yet known from the region. Most deep-sea sharks are dark brown or black to blend in with the darkness of the depths, but some species, like the lanternsharks, have bioluminescent organs that glow a shining pale green. This adaptation may either be to attract mates, maintain group cohesion in a school, lure smaller invertebrates within snapping range of their mouth, or possibly to create a halo-like effect to mediate the downwelling light from above and the tell-tale shadow a predator might see from below, making them effectively invisible. The newly described Ninja Lanernshark seemed to have few of these glow-in-the-dark organs, appearing less like a shark jack-o-lantern and more like a Japanese ninja dressed in black, and using their dark visage to their advantage, so prey may never see it coming. When Victoria consulted her young cousins to help with a common name for this new species, there were many options from the excited shark-loving kids, but Ninja Lanternshark, honed down from Super Ninja Shark, seemed appropriate.

The scientific name was of course in honor of Jaws author Peter Benchley. Several decades earlier I worked with him during a shark conservation program through the Cal Academy, and he admitted – what I had already heard through many other people – that he carried a burden of regret for the violent backlash against sharks unintentionally instigated by his book. For years afterward, he was not just an advocate for sharks, but a tireless campaigner in promoting ocean conservation. Long after his death, the Benchley Awards fund those who share his dream. Coincidentally, this year was the 40th anniversary of the publication of Jaws, and Victoria already knew Benchely’s widow, who was told about the new shark bearing her husband’s name. After several months of measurements, comparisons with other known species, and countless revisions of the manuscript, it was submitted to the Journal of the Ocean Sciences foundation, one of the rare but essentially important journals that still publishes species descriptions of fishes, and more importantly, one with open access, making this shark species immediately available to the world just this week. The ‘discovery’ of a new species of shark means nothing until a detailed, peer-reviewed study is finally made public. Fortunately, the bottles of Clicquot can still be popped.

Share the post "Ninja Lanternshark: the New Shark Species You Will Never See Coming"

I freaking love this website.

While I was working on a tender here in AK, we pulled one of these sharks out of the chute, didn’t know what it was and just now decided to try and look it up. It was caught along the Aleutian chain.