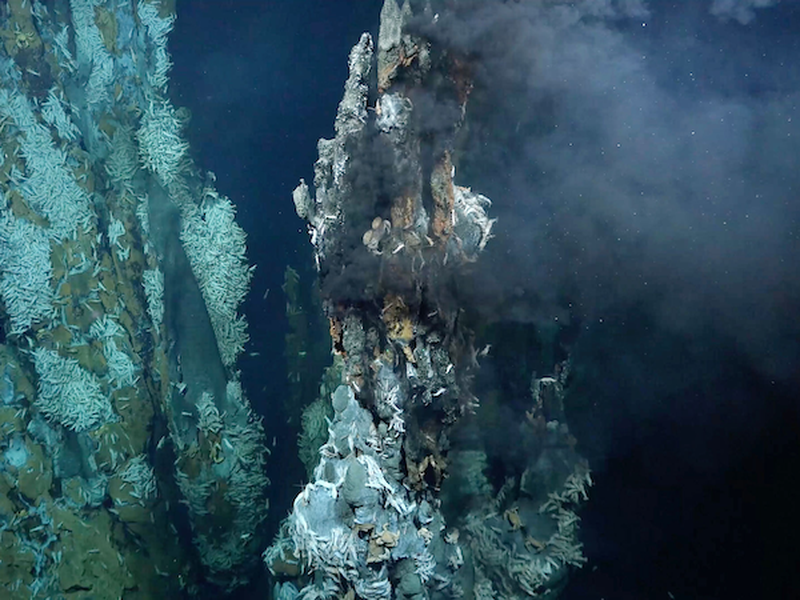

I have only seen a hydrothermal vent once, during Dive 73 aboard the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute’s Doc Ricketts. Unlike many deep-sea biologists, I have always been more interested in deep-sea mud than the flashy vents. However, seeing a hydrothermal vent was a major item on my bucket list.

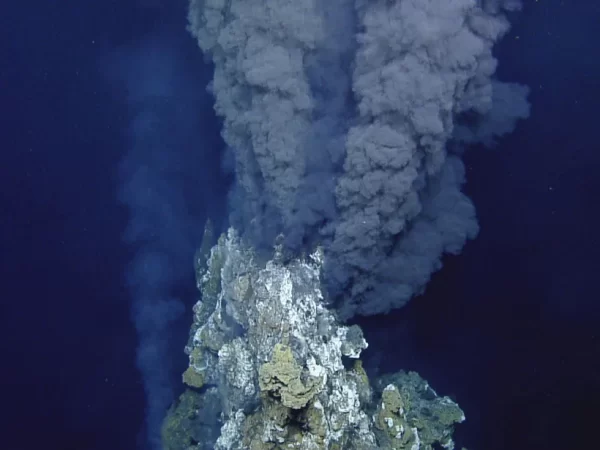

As I watched the monitor as we descend a 75-foot-tall chimney. Charcoal black to grey fluid is violently erupting from the top and several cracks along the chimney’s surface. You could see the shimmering sheen in the water, indicating that the temperatures were far above those of the surrounding, freezing abyss. Hydrothermal vents are home to the highest recorded temperatures on Earth. At oceanic ridges, where rocks are often brittle and fractured, cold seawater percolates down through Earth’s crust, gets superheated by magma, and rises back to the surface. Currently, the “Two Boats” vent in the Turtle Pits field along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge holds the record for the hottest hydrothermal vent, with fluid temperatures reaching up to 867.2˚F (464°C), nearly four times greater than the boiling point of water at 212˚F (100˚C). The extreme pressure prevents this boiling from actually happening.

At some vents lives the curious little worm, Alvinella pompejana. Discovered in the early 1980s by French scientists, the Pompeii worm is about 4 inches long with tentacle-like, scarlet gills on its head. Its name hints at its high-temperature habitat, being derived from the ill-fated Roman city of Pompeii, destroyed abruptly during an eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. The scarlet worm is found on the sides of hydrothermal vents, with its tube often reaching across the chimney to access some of the hottest vent fluids. The worms can be briefly exposed to 212˚F (100˚C) waters, although temperatures adjacent to the worm’s tubes more often range between near freezing and 113˚F (45˚C). In fact, the rear end of the species likely experiences extreme heat while the front end experiences extreme cold, making it the most eurythermal (capable of surviving a wide range of temperatures) species on earth.

How Alvinella pompejana survives in this boiling hot environment is still somewhat of a mystery. One theory is that the worm can keep itself cooler, between 68-83°F, by pulling cold water into its tube when it moves in and out, and with the help of bacteria that circulate the water around its body. This gray layer of bacteria covering the worm’s back, besides moving water, may also provide it with a sort of thermal blanket. The worm’s skin and connective tissue also have the most heat-resistant proteins known, thanks to their special structure. Additionally, the worm’s DNA has more triple bonds from guanine-cytosine (GC) pairs compared to other similar species, which helps it stay stable at temperatures up to 190˚F (88°C).

Share the post "A Journey to the Hottest Place on Earth: Hydrothermal Vents and the Resilient Pompeii Worm"