Sub-Neritic Gentrification

For November we will be doing some deep thinking about deep-sea mollusks in an attempt to understand the complex history and adaptations of these animals living in the depths of our oceans. Biodiversity of today’s marine snails can be traced to several different ecological and environmental phenomena, but in the Deep-Water Helmet Shell Galeodea keyteri, it is likely a case of adaptive radiation exploring new realms. The Helmet Shells (Cassidae) are a speciose group of large, shallow-water tropical and temperate marine snails that range among the intertidal coral rubble and sand flats to offshore muds, but as this evolutionarily successful group of gastropods continued to diversity into different niches, several species moved into deep-water to establish new ways of living. At these depths staying alive presents serious challenges with an extremely cold, low oxygen, nutrient-poor, and high-pressure environment, so some deep-water species trended to smaller, slow-growing physiologies like as a way to successfully conserve energy and resources. Since the dark depths lack sunlight needed for algae to grow, most species of deep-sea mollusks are either scavengers or predators, with little resources for vegetarians to survive. Like all Helmet Shells, Galeodea keyteri is a carnivore, specializing on starfish, brittle stars, and urchins. Catching their slow-moving prey with a muscular foot, glands in the proboscis secrete a fluid rich in acids that dissolve the echinoderm’s calcium-carbonate skeletons, while a radula drills into the weakened parts of the body to extract nutrients from their internal organs. A tough environment requires innovative strategies and hardy adaptations for a species to survive. Ain’t natural selection grand?

Molluscan Methuselah

While some species of deepwater mollusks are derived from shallow-water taxa that extended into and adapted within deep ocean ecosystems, other taxa of marine mollusks are taxonomic geezers with a much longer history. The Slit Snails (Pleuorotomariidae) are perhaps the oldest still-living lineage of marine snails, extending back in the fossil record more than 500 million years. Named because of its long slit at the aperture allowing for extension of their respiratory siphon, they were abundant in the shallow reefs throughout the world. Between the Late Cretaceous (ca. 90 million years ago) and the middle Eocene (ca. 40 million years ago) is when most modern lineages of shallow-water reef-living gastropods originated and diversified, and also the time when slit shells seem to disappear from that same fossil record. Among paleontologists and malacologists, the general hypothesis is that these modern taxa somehow out-competed the slit shells for food, or perhaps were more adapted to changing marine climates or fluctuating sea levels of the time, forcing the slit shells into progressively deeper and deeper water. This type of ecological displacement and bathymetric submergence has been seen in many other deep-sea groups, including corals, crinoids, brachiopods, and fishes. Today, slit shells are found in depths exceeding 3,000 meters, living the hi-life eating sponges in a cold, dark, lonely, nutrient-poor world.

Die-Hardest

As far as the origins of deep-sea gastropods go, we’ve visited two scenarios: new lineages of shallow-water snails radiating into deeper waters, and those formerly shallow-water taxa that have been out-competed in the shallows and forced into deeper, less productive habitats. But there’s a third group of deep-water snails that are so tough, so extreme that they can live in shallow and deep water. Here is the Checkered Hairsnail (Trichotropis cancellaria; Capulidae), the James Bond, the Bruce Willis, and the Rock all coiled up into one extreme snail that ranges from the intertidal zone to depths of nearly 2,000 ft. (600m). Is it true grit or it’s hard-boiled soul that make it impervious to the relentless cold, pressure, and darkness of the deep sea? Their broad range is more likely the result of two things: (1) a wide and variable physiology that can tolerate the extremes of shallow to deep; and (2) its broad diet that it can obtain at any depth. You see, the Checkered Hairsnail is a suspension-feeder, meaning it feeds on the decomposing bits of animal debris suspended in the water, which it traps by sticky mucous, and that kind of detritus is found in all habitats. However, it’s a sneaky critter. When the floating slurry of decomposition becomes scarce, they will parasitize tube worms by inserting their proboscis down the mouth of the worm and pumping out the contents of the worm’s stomach. Evolution: the weirder the better.

Slo-Mo Snail

Shallow-water gastropods live the good life. Warm water, a sunny sea rich in oxygen, and plenty of food provides them the metabolism to live fast, grow big, and die young, relatively speaking, of course. The flipside in the deep sea is a life of constant near-freezing cold, little available food, and water suffocatingly sparse in oxygen. This shell of the Catalina Turrid (Antiplanes catalinae, Pseudomelatomidae) who lives at depths of up to 4800 ft (1460 m), tells its story of life in this harsh realm. Growth lines, which indicate the increase and cessation of shell development, are seen as wide bands often far apart in curving spire of fast-growing shallow-water shells. In this species, the growth lines are close and compact, showing very slow growth and likely a long life. Their low metabolism provides little extra energy for their minimal growth and reproduction, so these snails probably take the developmental route of the tortoise over the hare. This shell tells another and more concerning story. Once only collected during deep-ocean trawls by research vessels, this species was prized by collectors as a rarity and an oddity. With commercial fisheries abandoning over-exploited fishing grounds along the shallower coasts, fishing has gone into the deep ocean to tap into those fragile resources. This specimen was taken as unintentional bycatch by a deep-water shrimp trawler, and though it wasn’t the target of the fisheries, the sparse populations of these slow-growing snails cannot sustain even the modest impact by commercial fisheries

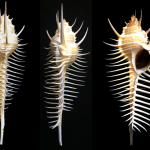

Post-Docs Please Enquire

The curse of working with deep-sea gastropods is how few specimens are in museum collections, and what very little is known about them. That too is the siren’s call of opportunity in deep-sea malacological research. The Japanese Pagoda Shell (Columbarium pagoda, Turridae) has been known to science for close to 200 years, based on relatively few well-documented specimens in museums and private collections scattered throughout the world, yet virtually nothing is known about their ecology. Diet, trophic niche, age, growth rates, reproduction, population structure, predators, parasites, physiology, ecological associations, movements – none of that has been adequately documented. If all mysteries in the ocean were solved, there would be no jobs for future under-paid post-docs or over-worked assistant professors. Those with grant funding, a modicum of workaholism, and access to deep-sea technology could pioneer new directions into a richer ecological understanding of the deep ocean’s marine mollusks. That siren’s call can just as easily dash unfeasible projects on the rocks of financial destitution and lead to deep regret of one’s research program and entrée into a life of constant self-medication and personal validation. These mysteries await the bold, but favor the wise.

Not actually about the mollusks, but going deep anyway: http://www.ibtimes.com/flight-mh370-update-19th-century-shipwreck-found-during-sonar-search-southern-indian-2262735