By now you’re probably aware that your entire skin surface (and every orafice) is swarming with millions of microbes. The human microbiome is pretty sexy science these days, but we’re not the only species that hosts our own customized microbial communities.

A LOT of marine species have microbiomes too, and this topic is a hot new field of research. The coral holobioint is probably the most well-researched example. But for now, let me introduce you to the microbiome of my nematode friends.

The “badass microbiome award” goes to nematodes in the genus Robbea, because they *literally* carry around a coat of bacteria on the outside of their body. Robbea worms live in the sediments around seagrass beds, which are rich in sulfur compounds. And sulfur is exactly what their microbiome bacteria like to gobble up:

The worms migrate between oxygenated, upper sand layers and anoxic, sulfidic, deeper ones (Ott et al., 1991) allowing the bacteria to obtain the oxygen they need as eacceptor and the sulfur compounds (e.g. hydrogen sulfide, thiosulfate) as edonor (Polz et al., 1992; Hentschel et al., 1999). Stable carbon isotope incorporation experiments showed that the ectosymbionts are the major components of their host diet (Ott et al., 1991). [Bayer et al., 2009]

In other words, these nematodes are a party bus for their microbiome bacteria. But then shiz gets real when the party ends, because these nematodes then turn around and EAT the bacteria they carry around. No microbes gonna mess with Robbea.

What’s even crazier is that Robbea nematodes aren’t born with their microbes – much like the human microbiome, these bacteria are acquired from the environment. DNA sequencing seems to tell us that these symbiont bacteria can be found hanging out in seawater–hopefully not getting into any trouble–prior to latching onto their worm hosts.

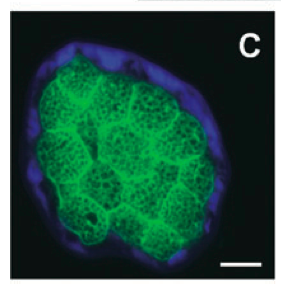

Astomonema nematodes have a less tumultuous relationship with their microbiome; they’re more of a gentle shepherd compared to hotel-room-trashing Robbea rockstars. Astomonema species have pretty much evolved into a garden for microbes, herding and nurturing endosymbiont bacteria inside their body wall. In fact, this group has become SO reliant on their microbiome, that evolution has decided these worms don’t need a mouth, anus, or functional digestive system anymore (these features being reduced or absent).

…bacterial symbionts completely fill the gut lumen of Astomonema sp., suggesting that these [bacteria] are their main source of nutrition…symbionts use reduced sulfur compounds as an energy source to provide their hosts with nutrition. [Musat et al., 2007]

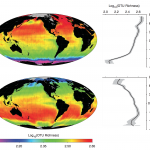

Nematode symbionts are related to symbiont bacteria found in other worms (particularly oligocheate worms, but also related to sulfur-utilizing symbionts of species found at hydrothermal vents). This raises some pretty cool evolutionary questions – for example, where (and in what organism) did these symbionts first evolve? Are similar microbiome species a result of convergent evolution? And are symbiont species widespread in the oceans, or only present in specific habitats where their hosts live?

We don’t have answers yet…but if I have my way, high-througphut DNA sequencing will soon shed some light on these questions. Stay tuned!

References:

Bayer C, Heindl NR, Rinke C, Lücker S, Ott JA, Bulgheresi S. (2009) Molecular characterization of the symbionts associated with marine nematodes of the genus Robbea. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 1(2):136–44.

Musat N, Giere O, Gieseke A, Thiermann F, Amann R, Dubilier N. (2007) Molecular and morphological characterization of the association between bacterial endosymbionts and the marine nematode Astomonema sp. from the Bahamas. Environmental Microbiology, 9(5):1345–53.

Share the post "Marine nematodes have a microbiome too (and it’s way cooler than yours)"

Fascinating post!

If Astonomema doesn’t have a mouth, how do its gut bacteria get their sulfur?

Astomonema has also been found in the deep sea recently and there several deep sea species that carry species specific bacteria on their cuticle. . Eubostrichus and Parabostrichus for instance. The latter has only been found in the deep so far. Re. Astomonema; there are some Nematologists that think the juveniles (which have been observed to have a mouth, but this hasn’t been confirmed) manage to take up the bacteria, more likely is that they get it via their bums or sexual orifices. The fact that they are stuffed with juicy bacteria makes them a yummy snack. … they often have their hindbody missing…ripped off and probably eaten by predators.

Through the cuticle, bums, sexual orifices…