![]() That’s right, you heard me—there are mushrooms that live in the sea. OK, well technically a mushroom is a fruiting body of a fungus with a cap, stem and gills, but lets take some dramatic liberties and run with it. A new draft manuscript recently necessitated that I review the literature on marine fungi – I had totally forgotten that marine fungi are so F#*%*G AWESOME!!

That’s right, you heard me—there are mushrooms that live in the sea. OK, well technically a mushroom is a fruiting body of a fungus with a cap, stem and gills, but lets take some dramatic liberties and run with it. A new draft manuscript recently necessitated that I review the literature on marine fungi – I had totally forgotten that marine fungi are so F#*%*G AWESOME!!

If nematodes are plagued by scientific neglect, marine fungi are crippled by scientific ignorance. We know they’re there, but we only have a vague idea of what they’re actually doing. (At least for nematodes, we can usually tell what they eat by the shape of their mouth). The cutting-edge textbooks for marine fungi–the only two in existence—were published in 1986 and 1954, respectively, and were typed on actual typewriters. I think you can see where I’m going with this.

In 1979 Kohlmeyer and Kohlmeyer wrote off marine fungi, essentially saying that this group was just so boring with less than 500 species. Today, this is laughable and we’re continually expanding our list of new species. Just a few months ago, Jones et al. (2011) announced the discovery of an old, divergent branch on the fungal tree of life. All this time a diverse group called the Cryptomycota had been lurking in dirt, pond muck, and deep-sea oozes – basically every environment on earth, but we had NO IDEA. Boring, you said? Ha!

Marine fungi are either completely restricted to oceanic habitats (obligate), or able to grow there as an extension of their normal range (facultative). You can find fungi anywhere you look: mud, beach sand, on algae, in corals, detritus in mangrove swamps, estuarine grasses, and even nestled in the gut of crustaceans (Hyde et al. 1998). Fungi are important decomposers in the marine realm, particularly because of their ability to decay wood (and it is additionally suggested that they also slurp up dead whales and other rotting animals). Some kickass species are destructive and deadly parasites, knocking off unlucky representatives from just about every phylum – bony fish to octopuses (correction: octopodes). Any aquarium enthusiast will warn of fungal infections that rapidly take advantage of their wounded fish. Conversely, other fungi are beneficial symbionts: for example, the fungus Turgidosculum complicatum lives in association with a green algae and offers protection from dreaded dehydration during low tides (Hyde et al. 1998). Anecdotal evidence also has me convinced that fungi live in association with nematodes—stay tuned, story in progress.

DNA data is beginning to reveal just how fungi can live and thrive in marine environments. The sea ain’t Kansas, and species such as Debaryomyces Hansenii (Hooley 2006) had to develop specialized abilities for life in an aquatic Oz. Compared to its relatives from terrestrial and airbone environments, D. Hanseii has a genome of similar size but greatly expanded in gene content—a diverse genomic armory that likely helps it to cope with the physiological challenges of a saline environment.

After the Gulf oil spill we heard incessant reports about oil-eating bacteria. But oil-eating fungi? You bet. Many fungal species secrete enzymes from their cells (such as lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase and laccase), which can externally break down an array of compounds in the surrounding environment, including industrial toxins and crude oil components (Atalla et al. 2010). Plus, the ability to degrade hydrocarbons seems to be a pretty common ability in random environmental isolates (Obire et al. 2008). Perhaps future bioremediation techniques will involve unleashing these marine mycelia? Marine Fungi have already been shown to produce antibacterial, antiviral, and antiprotozoal compounds (Bhadury et al 2006), so this application isn’t far fetched at all.

The most awesomest fact ever?? Fungi. Eat. Nematodes.

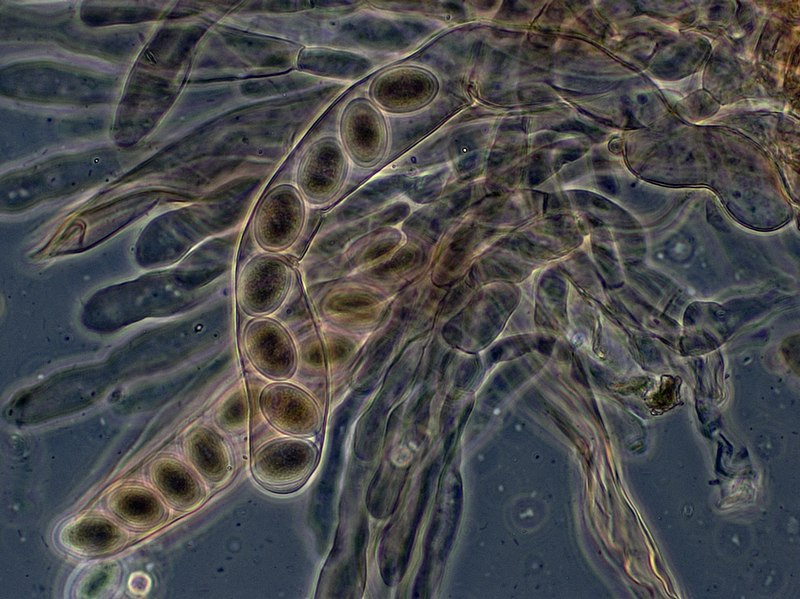

Imagine if a tree could lasso your body as you run past. That’s pretty much what some nematophagous fungi (and Vampyrellid protists) do in soils—capturing (very) motile nematodes, suspending their motion, and digesting them whole. Some fungi entwine nematodes with their rope-like hyphae and choke the poor worms to death. Other fungi inject their roots into a living worm, sucking out nutrients and killing the nematode as the fungal mass grows. [As another strategy, Vampyrellid amobae engulf nemtodes whole in a blob of goo (Sayre 1973)] To top it all off, nematophagous fungi unleash siren-like powers (perhaps by emitting sensual chemicals scents?) that attract unknowing, healthy nematodes towards their webs (Jansson and Nordbring-Hertz, 1979). Click here and also here for some AMAZING pictures and further information. There isn’t much evidence of nematophagous fungi from marine environments yet, but this is probably because we just haven’t looked. Marine sediments are literally infested with thriving masses of yummy, juicy nematodes.

Right now it seems like there are more questions than answers about marine fungi. How many species are there? What exactly are they DOING in marine sediments (are they active or dormant)? What cool chemical compounds/genes/predatory strategies are currently lurking unknown? And above all—why isn’t anyone paying attention? On the awesomeness scale of 1-10, marine fungi are an 11. I rest my case.

References

Atalla, MM, Kheiralla, ZH, Hamed, ER, Youssry, AA, & Abeer, AA (2010). Screening of some marine-derived fungal isolates for lignin degrading enzymes (LDEs) production Agricultural and Biology Journal of North America, 1 (4), 591-599

Bhadury P, Mohammad BT, & Wright PC (2006). The current status of natural products from marine fungi and their potential as anti-infective agents. Journal of industrial microbiology & biotechnology, 33 (5), 325-37 PMID: 16429315

HOOLEY, P., & WHITEHEAD, M. (2006). The genetics and molecular biology of marine fungi Mycologist, 20 (4), 144-151 DOI: 10.1016/j.mycol.2006.10.002

Hyde, KD, Jones, EBG, Leano, E, Pointing, SB, Poonyth, AD, & Vrijmoed, LP (1998). The role of fungi in marine ecosystems Biodiversity and Conservation, 7, 1147-1161

Jansson, H., & Nordbring-Hertz, B. (1979). Attraction of Nematodes to Living Mycelium of Nematophagous Fungi Microbiology, 112 (1), 89-93 DOI: 10.1099/00221287-112-1-89

Jones, M., Forn, I., Gadelha, C., Egan, M., Bass, D., Massana, R., & Richards, T. (2011). Discovery of novel intermediate forms redefines the fungal tree of life Nature, 474 (7350), 200-203 DOI: 10.1038/nature09984

Kohnlmeyer, J. and Kohlmeyer, E (1979) Marine Mycology:The Higher Fungi. London: Academic Press

Obire, O, Anyanwu, EC, & Okigbo, RN (2008). Saprophytic and crude oil degrading fungi from cow dung and poultry droppings as bioremediating agents Journal of Agricultural Technology, 4 (2), 81-89

Sayre RM (1973). Theratromyxa weberi, An Amoeba Predatory on Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. Journal of nematology, 5 (4), 258-64 PMID: 19319347

Great post – I knew about the nematode-eaters, but nothing at all about marine Fungi.

Coming soon to a scientific journal near you, Thaler et al. 2011 in “Marine fungi continue to be bad-ass”

Cool post! As a mycologist, I can’t tell you how nice it is to read something positive about fungi coming from outside of the mycosphere. Yes, marine fungi are amazing, and they are getting more amazing all the time. Keep an eye out for work by Anthony Amend on incredible diversity of fungi that inhabit corals (the subject of a fabulous talk at the Mycological Society of America meeting last week). The fungal tree of life is getting twiggier by the day…

Bam! Ascomycete phylotypes recovered from a Gulf of Mexico methane seep are identical to an uncultured deep-sea fungal clade from the Pacific – http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1754504811000729

I wish DSN had a like button for this comment

You forgot to tell about metabolites from marine fungi. That would be a great story.

Gutiérrez MH, Pantoja S, Tejos E, Quiñones RA. 2011. The role of fungi in processing marine organic matter in the upwelling ecosystem off Chile. Marine Biology, 158: 205-219

Nice post.

Wish to join team of marine mycologists. Any recommendation?

I’d love to see another fungi-related post…that’s just the mycologist in me, though.

Marine fungi definitely encompass an under-appreciated and under-explored field. I read this post a while back, absolutely loved it.