David Honig is a graduate student in marine science at Duke University in the lab of Dr. Cindy Van Dover. He is participating in LARISSA, a 2 month multinational expedition to study the causes and consequences of the ice shelf collapse. He will be posting regular updates on the expedition exclusively for Deep Sea News readers!

David Honig is a graduate student in marine science at Duke University in the lab of Dr. Cindy Van Dover. He is participating in LARISSA, a 2 month multinational expedition to study the causes and consequences of the ice shelf collapse. He will be posting regular updates on the expedition exclusively for Deep Sea News readers!

——————————

9 January 2010

Whalebone lander recovery

Whales are huge. The largest whale species can tip the scales at 30-150 metric tons. Anyone who has stood next to a beached whale can attest to the sheer magnitude of flesh this represents. So what happens when these city-bus-sized sausages sink to the seafloor? It turns out that sunken whale carcasses, or “whale falls,” sustain extraordinarily diverse communities of benthic invertebrates. Some invertebrates found at whale falls, such as gutless “zombie worms,” are specifically adapted to feed on bone and may depend upon a regular rain of whale carcasses for the perpetuation of their species. From an ecological perspective, dead whales are important.

LARISSA provides a rare opportunity to survey this poorly-studied component of benthic diversity in the Southern Ocean and provide insight into how human activity (i.e. whaling) may have had unforeseen impacts on the Antarctic ecosystem. In collaboration with researchers from Chile, Sweden and the UK, we are conducting a survey of whale-fall fauna occurring in waters around the Antarctic Peninsula.

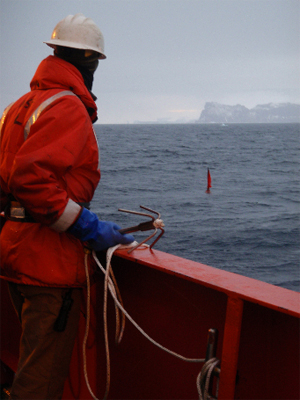

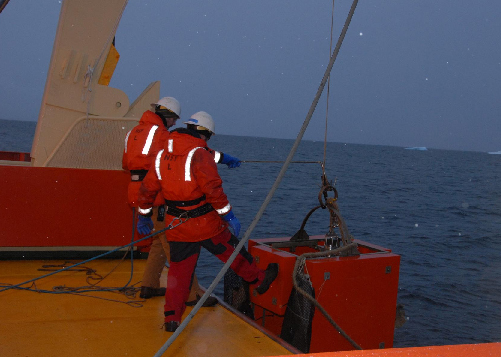

Yesterday evening we stopped at Vega Island to recover whale bones that our Swedish collaborators deposited at a depth of 650 meters in January 2009 as part of this larger survey. Instead of diving to the seafloor to retrieve the bones, we had the bones come to us via a “whalebone lander” that surfaces when acoustically prompted from the ship. The whalebone lander consists of a cubic aluminum frame surrounding an acoustic release—a cylindrical device with claws—that grips ballast. A coded ping from the ship causes the acoustic release to let go of its ballast and the lander, now positively buoyant, returns to the surface where it is easily recovered.

At least, that is how landers are supposed to work. In reality, landers can fail to ascend for a variety of reasons. The acoustic release can sustain damage when settling on the seafloor or run out of batteries. The lander can be mired in deep sediment with insufficiency buoyancy to break free. Or the ballast, once released, can settle onto the lander frame and pin the lander against the seafloor.

These possibilities were running through our minds when the whalebone lander failed to ascend after we pinged several “let go of the ballast!” commands. We were almost resigned to moving on when keen eyes on the bridge spotted our target at the surface. After hauling the lander and its aromatic, 150-pound cargo of whale bones onto the back deck, the reason why it failed to ascend became obvious. The entire lower third of the lander was stained black from being submerged in anoxic sediments. It had been stuck in the mud.

Dr. Craig Smith, Dr. Laura Grange (both University of Hawaii at Manoa), and Dr. Mike McCormick (Hamilton College) and I will spend the next few days counting sorting, and preserving invertebrates and bacterial mats we find attached to these bones. How many invertebrate species have colonized the bones? What do they eat? Are they isolated from whale-fall communities west of the Antarctic Peninsula? Does their genetic diversity reveal a recent population bottleneck—the legacy of whaling in the Antarctic? The data we collect from the Vega Island lander will help answer these questions, providing a baseline of knowledge on a little-known but fascinating subset of the Antarctic marine environment.

One Reply to “Dispatches from Antarctica – Whalebone Lander Recovery”

Comments are closed.