Guest post by Dr. Melissa Betters

“They got it!” echoed shouts down the hallways of the Research Vessel Atlantis in Fall 2018. The whole science crew knew what it meant: The elusive polychaete worm, seen numerous times during our deep-sea dives at the Pacific Costa Rica Margin, had finally been captured. Now, it’s been formally described in PLoS One.

The research cruise in question was one of three that surveyed the cold seeps off the coast of the Pacific Costa Rica Margin from 2017-2019. This region is a subduction zone – where one tectonic plate is subducting beneath another. This tectonic activity fuels cold seeps in the area, where chemicals are expelled from the ocean floor that can sustain chemosynthetic life. While seepage had been suspected in this region since 2002, these three cruises represented one of the most intensive sampling efforts in the area to date. One seep site in the region – “Mound 12” – is located about 1,000 m (3,280 ft) below the surface. While we had managed to collect a dizzying array of life here from snails, to tubeworms, to crabs, to mussels, one animal continued to evade our grasp: The Carpet Dragon.

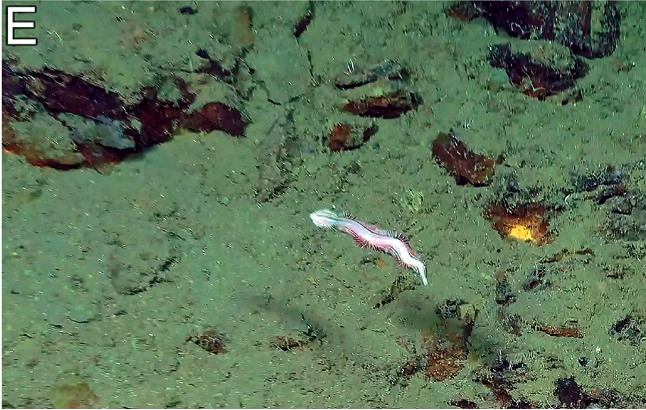

Okay, it’s not a dragon. It’s also not a flying carpet. But dive videos of individuals seen swimming just above the ocean floor sure looked a lot like both! As scientists aboard the ship didn’t know what it was and were fairly certain the species had never been seen before, the moniker stuck. At about 4-5 inches in length, it could be seen gliding past the cameras with undulating grace, its iridescent parapodia (paddle-like structures used for swimming) dazzling in the sub lights. First observed back in 2009, the Carpet Dragon had eluded capture for nearly a decade. This time, however, the operating team of the deep submergence vehicle (DSV) Alvin, vowed to change that.

Several dives to Mound 12 yielded sightings, attempts at capture, but still no specimen. The science team was getting nervous. What if we had to finish our expedition with no dragon in tow? Then, on the day before Halloween in 2018, Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott finally managed to capture a live specimen and bring it to the surface. The science team was buzzing with the news, anxiously awaiting Alvin’s ascent to the surface where we could finally see this specimen up close. We were not disappointed.

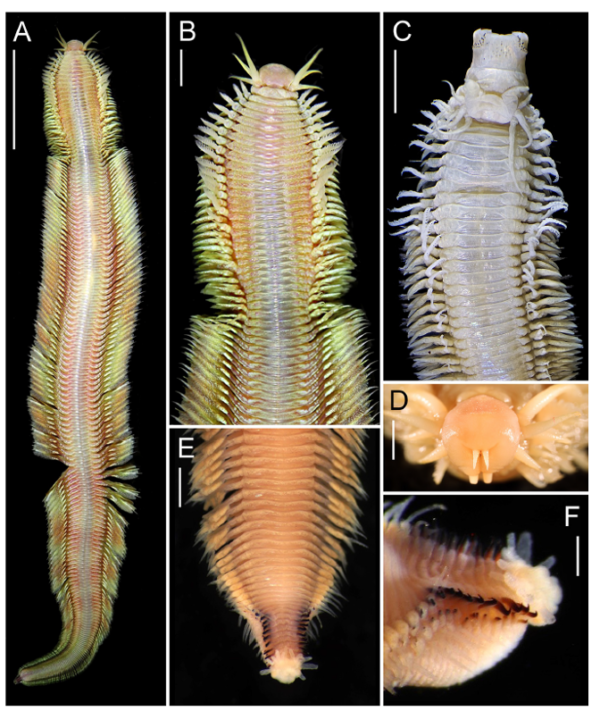

The Carpet Dragon, or Pectinereis strickrotti as it’s now officially called, is a polychaete annelid (“Annelida” = Broad animal phylum including all segmented worms; “Polychaete” = Broad class of marine annelids). Specifically, this worm sits within the family Nereididae de Blainville, 1818, which currently includes more than 700 species! While nereidids are found in both shallow and deep water, deep-sea and cave-dwelling nereidids share similar features of “darkness syndrome,” such as having reduced or no eyes and very long appendages. This species, however, is unique among all nereidids in having, among other things, parapodial projections near its head that are modified to function as gills, a hook-shaped acicula (= the strong internal bristle that adds structural support to the parapodia), and a fourth epitokal body region (most only have 3). These unique features not only mean that this is a new species, but also that it belongs in its very own genus, too! Its genus name combines the Latin word for comb (“pectinis”) with the name of the Family (“Nereis”) referencing its unique, comb-like gill structures. Its species name honors Mr. Strickrott, the Alvin pilot that finally captured the beast.

The individuals seen swimming around Mound 12 were found to be male epitokes – Free-swimming, sexually mature forms of polychaetes. Epitokes may form in two ways: (1) An sexually immature polychaete (an “atoke”) stays burrowed in the sand and buds off numerous reproductive epitokes to go and do its sexual bidding (think of it as going on dozens of one-night-stands without ever having to leave your couch), or (2) atokes go through the transformation themselves into a sexually mature epitoke. In both strategies, the epitoke dies once its gametes are released.

Pectinereis strickrotti is just one example of the myriad of unknown species in the deep ocean, and it is believed that there are numerous undiscovered species of nereidids in the deep ocean just waiting to be described. The energetic hunt for the Carpet Dragon may seem silly, but was ultimately a testament to the enthusiasm, perseverance, and teamwork needed to propel scientific exploration forward. What might scientists find next?

Villalobos-Guerrero, Tulio F., et al. “A remarkable new deep-sea nereidid (Annelida: Nereididae) with gills.” Plos one 19.3 (2024): e0297961