Twelve years ago this month, a super squid was captured.

On April 1, 2003, a massive squid was pulled up from the sub-antarctic waters south of New Zealand, and while a bit mangled by the fishing lines that captured it and suffering from additional damage from packing and travel, it still measured 5.2 meters (nearly 18 feet long) and weighed 300 kilos (660 pounds), making it one of the largest invertebrates ever studied. This specimen made its way to the Te Papa Museum in Wellington, New Zealand where it became the object of intense study among those with a particular obsession with squid. It turned out this was just a young one.

On April 1, 2003, a massive squid was pulled up from the sub-antarctic waters south of New Zealand, and while a bit mangled by the fishing lines that captured it and suffering from additional damage from packing and travel, it still measured 5.2 meters (nearly 18 feet long) and weighed 300 kilos (660 pounds), making it one of the largest invertebrates ever studied. This specimen made its way to the Te Papa Museum in Wellington, New Zealand where it became the object of intense study among those with a particular obsession with squid. It turned out this was just a young one.

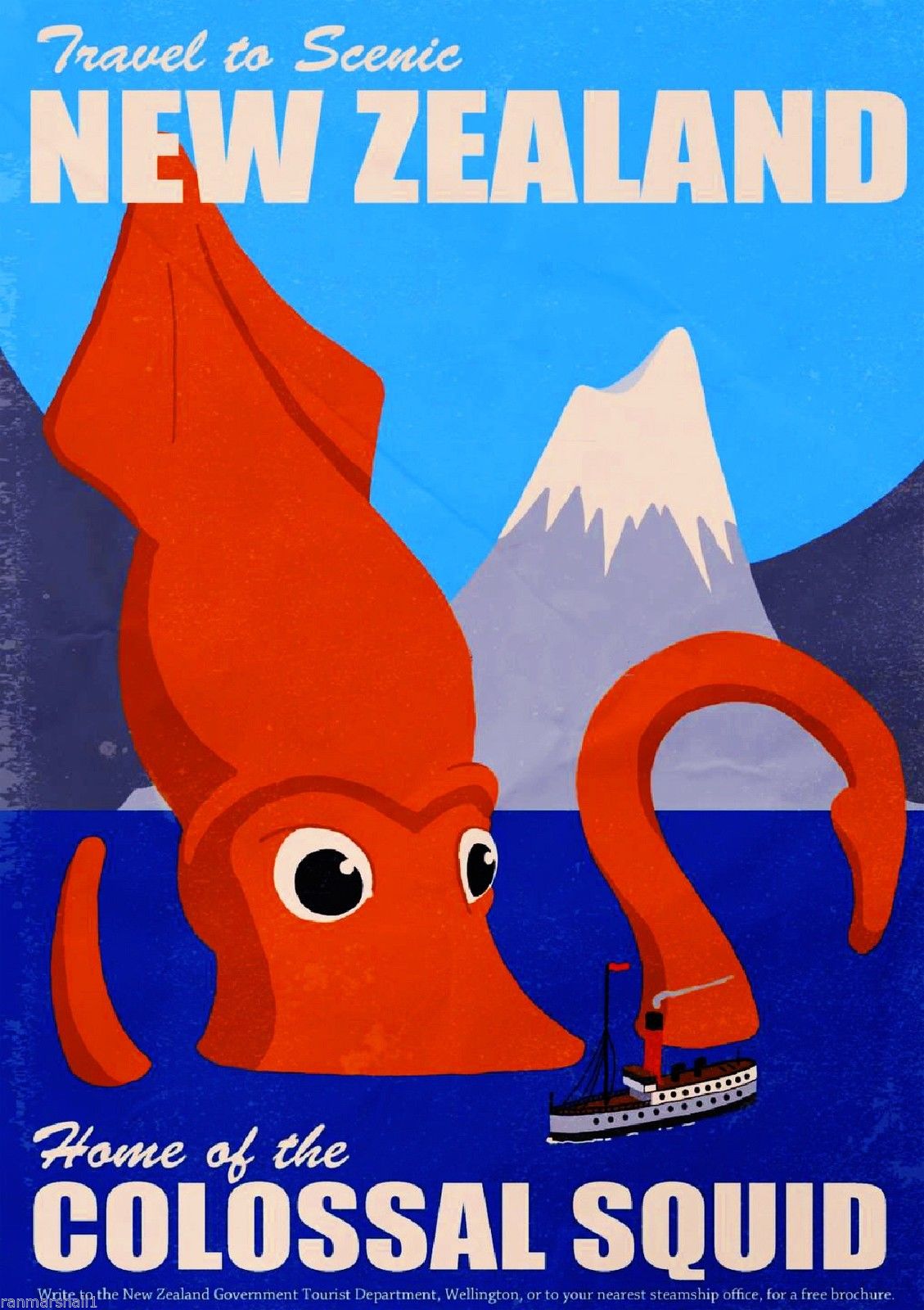

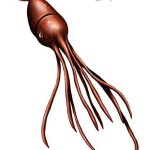

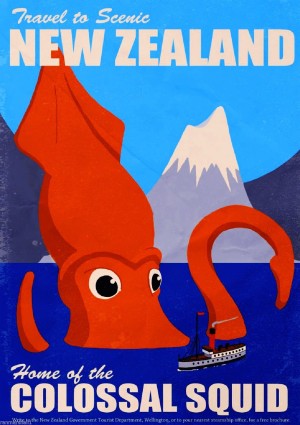

The Colossal Squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) was first described in 1925 on the basis of several tentacles taken from the stomach of the squid-eating sperm whale;  these tentacles and the distinctive sharp hooks on the suckers were unique enough to warrant designation as a new species. In the intervening decades juveniles and chunks of larger individuals were collected and described, and yet an entire adult specimen was not to be known until decades later. Whaling stations routinely examined sperm whale stomachs to identify what – and possibly where – they were eating, and while longer arms and tentacles from other squid species had been examined from whale bellies, the relatively modest tentacles from the first Colossal Squid didn’t really indicate what a massive beast the squid would turn out to be until the 2003 specimen was found.

these tentacles and the distinctive sharp hooks on the suckers were unique enough to warrant designation as a new species. In the intervening decades juveniles and chunks of larger individuals were collected and described, and yet an entire adult specimen was not to be known until decades later. Whaling stations routinely examined sperm whale stomachs to identify what – and possibly where – they were eating, and while longer arms and tentacles from other squid species had been examined from whale bellies, the relatively modest tentacles from the first Colossal Squid didn’t really indicate what a massive beast the squid would turn out to be until the 2003 specimen was found.

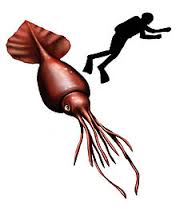

In February 2007 another Colossal Squid was accidentally snagged as it pilfered Patagonian Toothfish from a longliner plying the Antarctic waters of the Ross Sea south of New Zealand. Barely alive but relatively undamaged, the dying specimen was filmed, photographed, and readied for travel to the Te Papa. This adult, weighing some 495 kilos – more than half a ton – was easily the largest squid ever captured, If not as long as the Giant Squid (Architeuthis dux), its sheer mass made it the largest non-vertebrate animal alive on the planet. Today, this Colossal Squid is in eternal repose, inanimate and floating in a formalin-filled glass-topped casket for public viewing in the Te Papa Museum, not unlike the embalmed corpse of Vladimir Lenin inside his brick mausoleum in Russia’s Red Square, but far more interesting. Since 2007, several more Colossal Squid were received by the Te Papa, including one obtained just last year, but are housed in the off-site collections facility several blocks from the museum, and none are as large as this one.

Prior to construction of Te Papa’s Colossal Squid exhibit, an exhaustive anatomical study was performed on the animal. Dissection of one of the internally-lit eyes that could project illumination toward its tentacles made it clear that was it adapted for hunting fish & other squid in the deep, dark Antarctic waters, and by deep, we’re talking more than a kilometer underwater. It was, in fact, the largest eye of any animal yet known. The relatively small

Prior to construction of Te Papa’s Colossal Squid exhibit, an exhaustive anatomical study was performed on the animal. Dissection of one of the internally-lit eyes that could project illumination toward its tentacles made it clear that was it adapted for hunting fish & other squid in the deep, dark Antarctic waters, and by deep, we’re talking more than a kilometer underwater. It was, in fact, the largest eye of any animal yet known. The relatively small  tentacles of this species were made more lethal due to the serrated suckers on the eight arms of the squid – a common feature in many species of large squid – but also sharp hooks on the tentacular clubs that could swivel, thus keeping a firm hold on struggling prey. Most startlingly, the large beak of this squid was smaller than beaks of the same species taken from Sperm Whale stomachs, evidence that super-colossal Colossal Squid are alive and hunting in the southern seas.

tentacles of this species were made more lethal due to the serrated suckers on the eight arms of the squid – a common feature in many species of large squid – but also sharp hooks on the tentacular clubs that could swivel, thus keeping a firm hold on struggling prey. Most startlingly, the large beak of this squid was smaller than beaks of the same species taken from Sperm Whale stomachs, evidence that super-colossal Colossal Squid are alive and hunting in the southern seas.