But sometimes the hungry mouths that larvae need to avoid are their own parents and relatives.

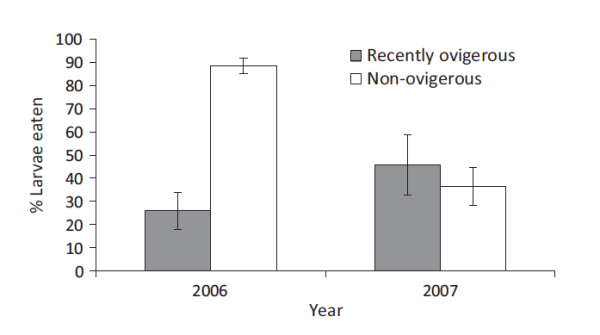

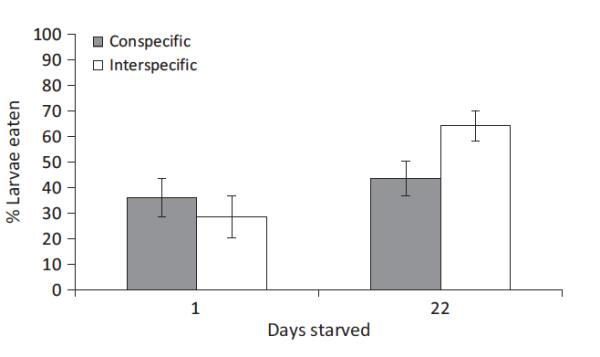

Many marine invertebrates suspension feed, basically straining plankton snacks out of the ocean. But what is a good parent to do when their own young gets mixed into the food bowl? Yellow shore crabs and European green crabs reduced their eating when they recently released young. Note I say reduced and not just stop. A hungry parent still needs to eat. Female crabs that recently carried eggs, i.e. ovigerous, ate only 25-30% of their own larvae. Non-ovigerous…well they got their ‘eat on’ consuming about 90% of larvae. However, a year later in 2007 there was little difference between ovigerous and non-ovigerous females in cannibalism of their own larvae. The authors hypothesized and then tested the idea that hungrier females would consume more of their own larvae. Twenty-two days of starvation increased the cannibalism of larvae by 30%!

So to sum up, larvae are fine just along as the parents aren’t too hungry. Miller, S., & Morgan, S. (2014). Temporal variation in cannibalistic infanticide by the shore crab: implications for reproductive success Marine Ecology DOI: 10.1111/maec.12172

Emery A.R. (1973) Comparative ecology and functional osteology of fourteen species of damselfish (Pisces: Pomacentridae) at Alligator Reef, Florida Keys. Bulletin of Marine Science, 23, 649–770.

“they are” = “they’re”