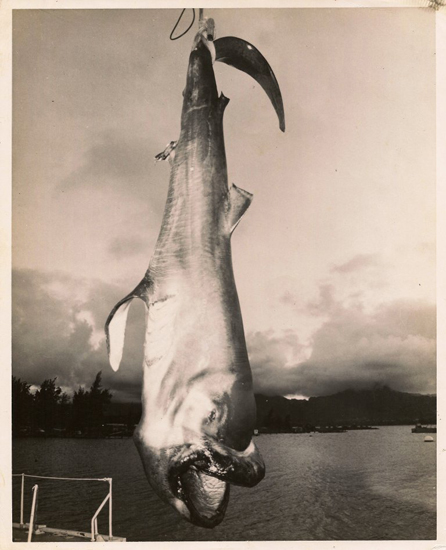

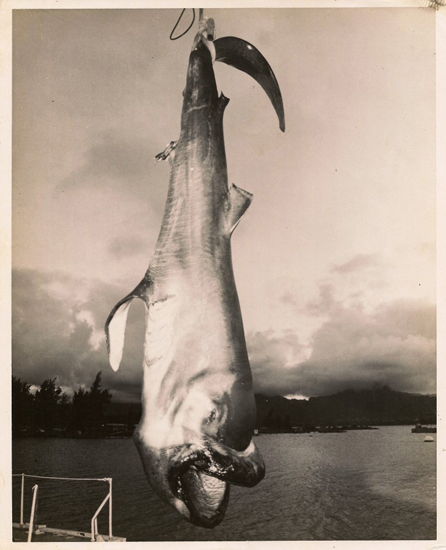

On 15 November 1976, a US Navy boat tracking Soviet subs in the Pacific was retrieving its sonar gear from deep water around Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands, and ran into a snag that would be one of the most profound zoological discoveries of the 20th Century. What the crew pulled up was a 16-foot long shark entangled in (actually swallowed) an underwater parachute anchor, and turned out to be something entirely new to science – a new species, genus, and even family of shark, and a bizarre one at that. Dubbed the ‘Megamouth,’ based on its huge gaping maw that allowed it to take big gulps of krill-filled water that it filtered through its gills, it finally earned a scientific name of Megachasma pelagios in 1983. To date, over 50 Megamouth sharks have been found in tropical and temperate seas around the globe. Despite the attention this odd shark gained at the time of its initial discovery, it actually helped to solve an even older shark mystery.

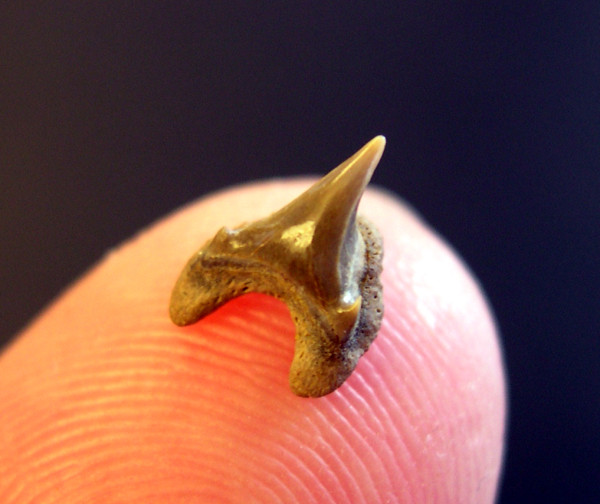

Digging in the marine sediments deposited when California’s Central Valley was a vast inland sea, paleontologists occasionally found rather tiny, strange-looking shark teeth that didn’t resemble those of any shark then known. And since there wasn’t any clear descendant to compare them to, and thus help in a scientific description and publication of this fossil species, these fossils from the 1960’s and 70’s remained a mystery, packed into tiny vials in archival drawers in several California museums. With the official 1983 paper describing the anatomy of the new Hawaiian Megamouth shark, it soon became clear that these unique fossil teeth now had a definite relation to an existing species. Megamouth had ancestors swimming in the ancient seas off California and Oregon nearly 24 million years earlier. Despite this new connection, and the abundance of specimens, the fossil species was never officially named until this year, nearly five decades later.

Why did it take five decades? Well that’s an interesting story. Anybody who works in any area of science knows how territorial researchers can be, often defending certain taxa as theirs alone to study, or even claiming entire scientific theories as their domain. When I first examined these fossil teeth in the early 1990’s for my doctoral dissertation on the evolutionary history of eastern Pacific sharks, at least six different researchers from four countries said that I shouldn’t bother describing this new Megamouth species because they were already on it, with a published description imminent, some said. A few growled ‘back-off’, so I did. Young, naïve, and really not wanting to make any enemies before my career ever started, I moved over to other projects and generally forgot about these fossils. Fast-forward 20 years later, and I get a note from Kenshu Shimada of De Paul University. I last met him as a budding shark evolutionary biologist at a paleontological conference in 1992, and in the 20 years since, he grew into a researcher far more prolific and dedicated than I was to fossil sharks. He asked if I was ever going to publish the description of the Megachasma fossils, which devolved into a complicated talk about who was doing what, when, with whom, and with what specimens. In all, I counted at least a dozen researchers from six countries that at one time or another had their hands on fossil Megamouth material with intent to describe the species – over a span of nearly 50 years. Moreover, our fossil teeth were beginning to show up for sale on EBay, scraped out of our type locality by weekend fossil hunters. We realized we had to work fast. At the end of our conversation, we pledged to finally describe the species. Others had their chance, now we’ll get it done.

Like in the script of an action movie, we first went to get one of our heroes out of retirement for this last attempt to name the fossil Megamouth. Bruce Welton, a UC Berkeley-trained fossil shark researcher who went to the dark (and far more lucrative) side of the sciences, having recently retired as a petroleum geologist for a major oil company. Neither of us had heard from him for years, but after a few prods through colleagues and old e-mail addresses, we got him. Not only was he interested, but he surfaced with a detailed early draft of the species description that had never seen the light of day. Quickly, we found the original type specimens, measured & photographed them, drafted illustrations, and exchanged many revised versions of the text, with the final copy being submitted in late 2012. Then we waited. I was paranoid about someone else scooping us, since so many specimens of our new species were now on the market, and many other researchers had seen, measured, and photographed our same material over the preceding decades, and people started hearing that we were working on those fossils.

Finally, after nearly a year with the reviewed, accepted draft in the que, the new species was published in the March issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. We named the fossil Megachasma applegatei after late fossil shark researcher Sheldon P. Applegate, a man who I often saw as a bit cantankerous in the field, and often tipsy at conferences, but always generous with his time and attention if you wanted to talk about sharks, and an inspiration to all three of us. He was one of the first people to be utterly confounded by the taxonomy of these tiny fossil teeth, and after the discovery of the Hawaiian Megamouth, he put the pieces together but never went past that. His later life as an American ex-pat in Mexico seemed to be more fun than the tedium of describing fossil sharks.

Before I even received my pdf copy of the paper, I got a half-dozen notes from other shark researchers thanking us for finally getting this paper out and naming the species. These teeth were not a secret, but they could never be properly cited in any scientific literature without a full published species description. Moreover, these teeth not only extend the lineage of Megamouth far earlier than previously known, but interesting characters of the teeth tell a broader tale of Megamouth’s evolutionary history. Since the Hawaiian Megamouth was so unique, researchers were scratching their heads as to where exactly it sat in the family tree of sharks, but the fossil teeth carry certain features that unite them with a group of sharks known as the Odontaspids, an old and abundant fossil group that still exists today and contains the predatory sand tiger and gray nurse sharks. So it seems that Megamouth evolved from a sharp-tooth fish eater, but later evolved into a filter-feeding planktivore where teeth where useless and became reduced in size, similar to the tiny seemingly vestigial teeth of Whale and Basking Sharks, the two other species of plankton-feeding sharks, but still retained enough of their ancestral dental morphology to unite these two groups. With a small step after a very, very long pause, elasmobranch science still marches on.

One Reply to “Enigmatic Megamouth Shark has Long-Lost Fossil Relatives”

Comments are closed.