When I first saw a sea sapphire I thought I was hallucinating. The day had been anything but normal, but this part will always stand out. I’d spent the afternoon on a small dingy off the coast of Durban, South Africa. It was muggy, and I’d been working for hours–-throwing a small net out, and pulling in tiny hauls of plankton that I’d then collect in jars. As I looked through one jar, the boat rocking up and down, I saw for an instant a bright blue flash. Gone. Then again in a different place. An incredible shade of blue. Maybe I’d been in the sun too long? Maybe I was seeing things? It wasn’t until I got back to the lab that I discovered the true beauty and mystery of these radiant flashes.

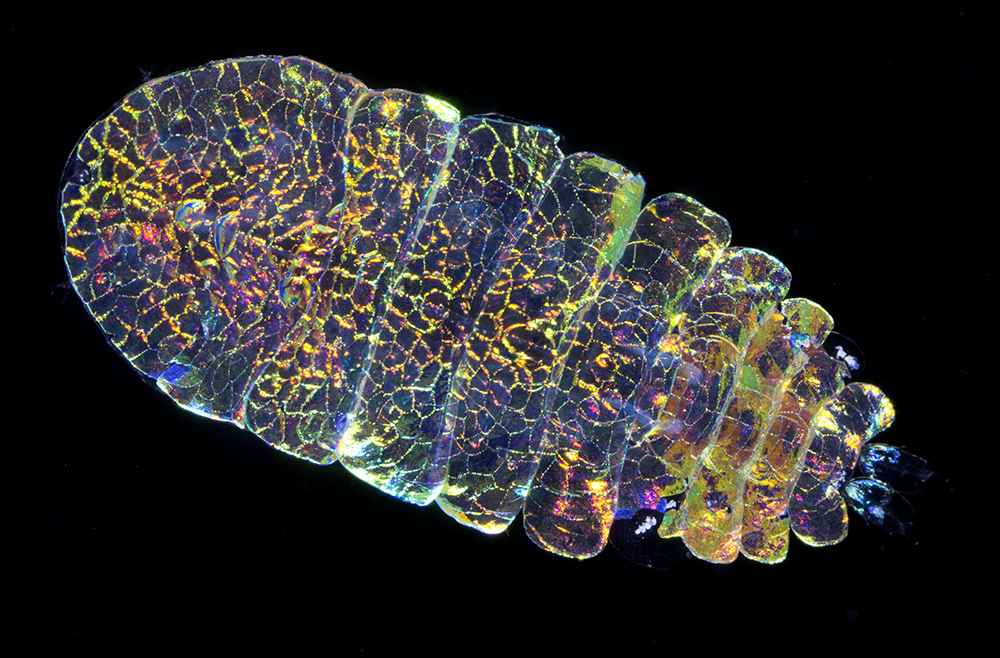

I’d like you to meet one of the most beautiful animals I’ve ever seen:

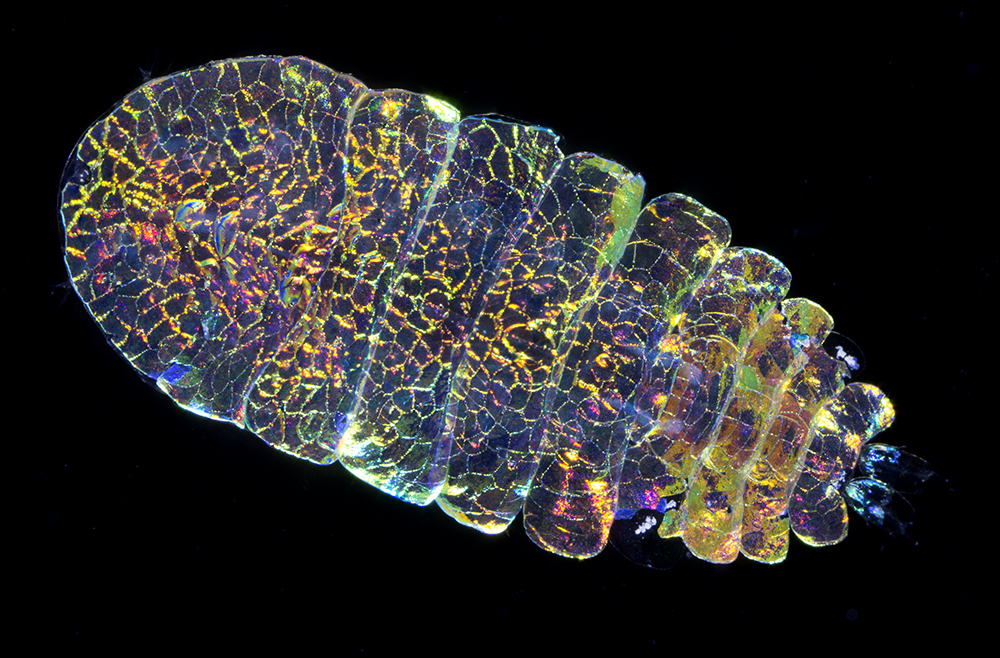

The small creature I’d found was a Sapphirina copepod, or as I like to call it, a sea sapphire. Copepods are the rice of the sea, tiny shrimp-like animals at the base of the ocean food chain. And like rice, they are generally not known for their charisma. Sea sapphires are an exception. Though they are often small, a few millimeters, they are stunningly beautiful. Like their namesake gem, different species of sea sapphire shine in different hues, from bright gold to deep blue. Africa isn’t the only place they can be found. I’ve since seen them off the coasts of Rhode Island and California. When they’re abundant near the water’s surface the sea shimmers like diamonds falling from the sky. Japanese fisherman of old had a name for this kind of water, “tama-mizu”, jeweled water.

The reason for their shimmering beauty is both complex and mysterious, relating to their unique social behavior and strange crystalline skin.

A key clue: this sparkle is only seen in males. Males live free in the water column, but females make their home in the crystal palaces of a strange, barrel-shaped jellies called salps. And though they’re not flashy, these parasitic princesses have huge eyes relative to males. Perhaps female sea sapphires look out upon an endless expanse of ocean sparkling with blue and gold, searching for the a particularly luminous shine. Or it could be that males use their shimmer to compete with one another, like jousting knights in shining armor, while the females watch on. About the social life of sea sapphires, we know very little. But how do they shine in the first place?

I was lucky to find one, but sometimes they are found in astonishing numbers. My friend and colleague Erik Thuesen once told me about his work on an ROV, as the submersible was coming to the surface, “it passed through this amazingly sparkling layer of iridescent Sapphrina”. A rare sight to see; not, perhaps, due to the rarity of these ocean gems, but the rarity at which we enter their world. Even as you read this, wherever you are and whatever you’re doing, they’re out there right now. Quietly shining in their own private universe of stars.

Work Cited and additional reading

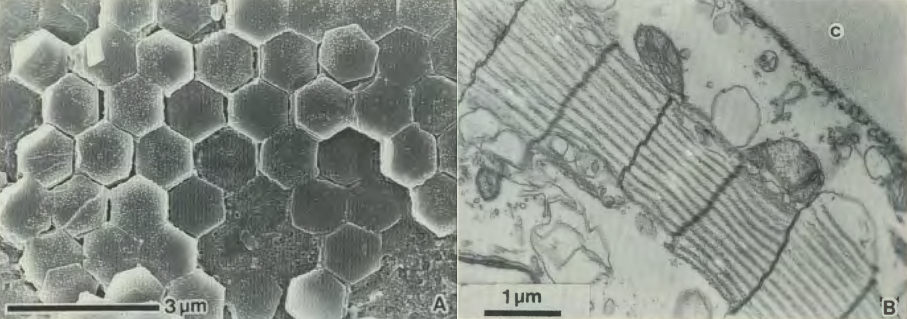

[1] J. Chae, S. Nishida (1994). Integumental ultrastructure and color patterns in the iridescent copepods of the family Sapphirinidae (Copepoda: Poecilostomatoida). Marine Biology, Volume 119, Issue 2, pp 205-210

Yuval Baar, Joseph Rosen, Nadav Shashar (2014). Circular Polarization of Transmitted Light by Sapphirinidae Copepods. PloS ONE. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086131

oooooo….shiny….

I have seen these on safety stops diving in the Tortugas, FL keys. They were not uncommon when oceanic water was inshore (if I remember correctly), Some dives you could see around 80-100 while going down and while at the safety stop on the way back up. This was most often when looking down (reflected light) and often flashing and disappearing fooling us as well as their predators. For a small size they are very conspicuous for that second.

This and cerataspis are my favorite swimming crustaceans.

Just a note that your caption for the side by side images is reversed.

Thanks! Fixed.

The iridescence reminds me of opal.

Me too! And we’re not the only ones, one species is actually named Sapphirina opalina!

What an amazing creature! I wonder if the cause for the coloring is similar to the iridescence in beetles and butterfly wings. I did a story about this for the NSF image gallery (see http://www.nsf.gov/news/mmg/mmg_disp.jsp?med_id=72733&from=).

Great story! I’ve never heard the term “liquid crystal” before, but it’s awesome! I bet it’s the same phenomenon as what we’re seeing here. The technical term is thin film interference, and this type of structural coloration can be found in a variety of iridescent animals.

I was wondering if you have seen this species arround mexican coasts

Yep! According to another researcher, the research trip Erik described was actually in Mexican waters!

Wow, super! It’s amazing

OOHHHH we had lots of salp around our lab in the earlier part of summer at Goat Island (New Zealand), and there was also iredecent blue flecks in the water….could this be it? So stunning! I wish I brought some to have a look under a microscope but we were just enjoying being in the water….

I bet they were!!! Really cool!

woahh! very cool…looks like nature has it’s own advanced techy spy stuff!

Great story and spectacular movie. do you know the nature of that cristalline structure ? is is Calcite ? or something else ?

thanks!

I guess it’s probably not mineral, but organic membranes –

rice? lice?

I’m not sure, and I’m not sure the authors are either. Here’s what the paper said: “this structure consists of 10 to 14 pairs of closely spaced membranes, lying parallel to each other and to the cuticular plane (Fig. 1B)…The spaces between the laminated membranes of the thin sections often had gaps of various sizes, suggesting that some hard materials originally present at the gap sites were lost during sectioning”

When a teacher & I saw the picture of this magnificent creature, the character, Rainbow Fish, was the thing that kept popping into our minds. Rainbow Dash was the second character that popped into my head. Funny, in a way…