Guest post by Dr. Melissa Betters

Are you afraid of the deep, dark ocean? If so, you’re not alone. Thalassophobia (fear of deep water) seems all too common these days from web articles titled “10 Bioluminescent Organisms That Better Cut That Freaky Sh*t Out Before I Call The Cops,” to sci-fi thrillers like “The Meg” (2018) to Tumblr posts like that of user jaclcfrost: “make no mistake i love the ocean with my whole heart but deep water terrifies me so much.. what’s goin on down there? nothing i want to be a part of.” Indeed, the deep ocean – aquatic, cold, dark – is about as opposite an environment from our own as we could imagine. As laid out in the 2018 book Beasts of the Deep: Sea Creatures and Popular Culture: “The deep sea offers us an oppressive and foreboding context – a space unexplored, unknowable, and overwhelming.” But what is the cost of viewing over 70% of our planet with aversion – and who benefits from it?

For centuries, humans have imagined all manner of monsters inhabiting the ocean’s depths. Yet, despite decades of research, little has changed about how we talk, or think, about the deep sea. When I was young, I was fascinated by the “alien” life that inhabited the deep. “We know more about the surface of moon…” Sir David Attenborough assured me in BBC’s Blue Planet (2001), than we know about the deep sea. It wasn’t until I was offered a place on a research expedition in 2017, however, that I would see this world for myself. One morning in September, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, I squeezed into the Pisces V submersible – a metal sphere no bigger than a small sedan. The water changed from blue to black as we descended to 1000 meters (~3280 ft). We were entering into a fabulously unknown world… Or, so I thought.

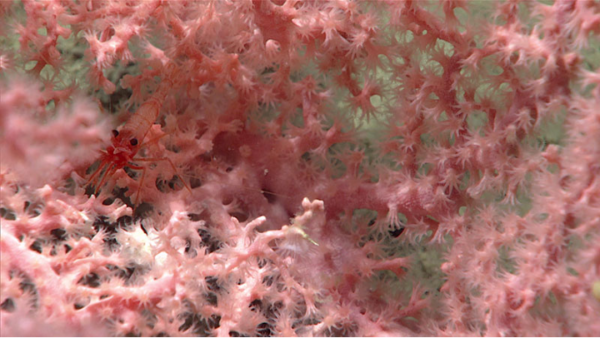

Mr. Terry Kerby, our submersible pilot, greeted each animal like an old friend (This was the Pisces V’s 889th dive, after all). Barracks, rattails, Chaunax, Callogorgia, Corallium, Desmophyllym, Chimeras, Dories, Ophiuroids… I was taken aback by how normal these animals looked. The fish were not the deformed oddities I had come to expect. The crabs just looked like crabs. The corals, like corals. Wasn’t this supposed to be an alien frontier?

I learned an important lesson on that expedition: What most people believe about the deep ocean is, at least partly, a lie. There are many reasons why deep-sea imagery might be misleading. For one, can be difficult to get a sense of scale. Ambiguity, paired with fear and imagination, is what makes animals like the Viperfish (Chauliodus spp.) look like something that could eat you for dinner, rather than its actual length of ~30 cm (~12 in). In 2012, an exhibitionput on by the Australian Museum displayed an “oversized model anglerfish” which has since circulated around the web, passing as a real specimen (Most midwater anglerfish (Melanocetidae) are rarely more than a foot long!). The infamous mugshot of the “blobfish” (Psychrolutes marcidus), aka the “World’s Ugliest Animal,” shows the violent result of a trip to the surface. As researchers Alan Jamieson and colleagues write, “…take a domestic cat, scour its hair off, drown it in near-freezing water, pressurize it to 300 atmospheres, photograph its face, and then declare it ugly. The cat scenario would certainly be met with immediate disgust and outrage but it is exactly what the image of the blobfish portray.” Others wish to incite fear, shock, or disgust. If you search the phrase “Deep Sea Creatures,” pages of image results are inevitably returned of twisted, grotesque, and bizarre creatures – some real, many fictional. All of this works to reinforce thalassophobia.

So, people fear the deep ocean. So what? Why should we care?

The real issue with fearing the deep sea is that it is actively under threat, and there is little public outcry in response. The more people hate the deep ocean, the less pressure there is to protect it. Fear has always been a powerful political tool. From colonization to resource extraction, exploitation of an area has always been easiest when people believe either (1) nothing lives there, or (2) what lives there has no value. When the former can no longer be claimed, tactics usually shift to the latter. In the case of the deep ocean, decades of research and exploration have long since shattered the illusion of an empty abyss. Thus, we shift to the latter. People protect what they love. What does that mean for what they hate?

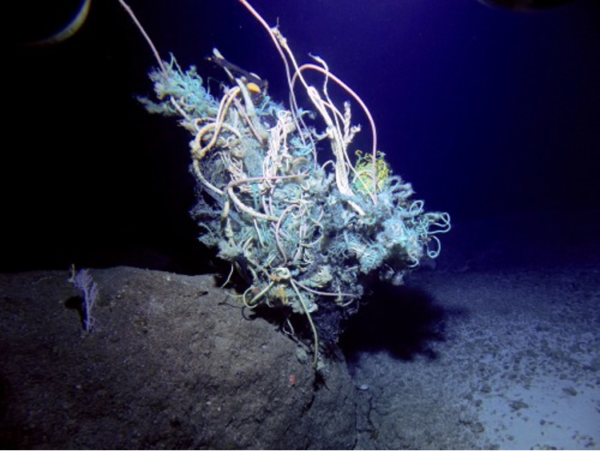

The deep ocean is part of our planet, subject to all its challenges and human impacts. Currently, over 3,400 deepwater drills extract oil and natural gas from the Gulf of Mexico, alone. As was vividly illustrated by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, which spewed an estimated 3.19 million barrels of oil into the Gulf, this is not without risk. To combat this need for oil, people are shifting to electric vehicles, but this has consequences for the deep ocean, too. Many areas of the seafloor are rich in rare earth elements needed for batteries like Nickel, Cobalt, and Lithium. Thus, deep-sea mining is being explored as a means of satiating this demand, threatening to “clear cut” an area roughly the size of the continental U.S in the Pacific Ocean. Deepwater fishing not only removes targeted species from the deep sea, but also more than 38 million tons of unmanaged, unintentional, or unused species (“bycatch”) each year. Even fishing gear alone can be destructive. Around 48 million tons of “ghost gear,” or fishing gear lost at sea, are unintentionally generated each year – about the weight of 240,000 blue whales. Ghost gear may entangle and kill sea life for decades and, as most gear is made of highly durable nylon, is one of the largest sources of plastic pollution in the ocean. If deep-sea ecosystems manage to evade all these threats, however, there are still rising CO2 levels and seawater temperatures to contend with.

If we want to protect the deep ocean, then we must actively change the way we talk about it. The deep ocean is a tapestry of beautiful environments that should be viewed with awe, interest, and fascination. For scientists, we must change how we present this place, shifting the focus away from its “alienness” to its complexity, uniqueness, and vital importance. For the public, we must make an active effort to learn about the reality of the deep ocean and combat misinformation. With resources available like NOAA’s Deep Ocean Education Project and livestreams of deep-sea dives, there’s never been a better time to learn about our deep oceans. Fear is never neutral. Being conscious of how emotions like fear and disgust can be used against us is a crucial step towards ocean stewardship. The deep sea is a frontier, but it is much less scary, and way more interesting, than you might think.

Share the post " The Cost of Fear: How Perceptions of the Deep Sea Hurt Conservation"