Osedax worms, or the ‘bone eating’ worms are little soft sacks resembling snotty little flowers. The “bone devourer” is not quite accurate as the worms do not actually feed on the bone mineral, but rather the fats within the bone matrix. It’s just the Osedax females that do the feeding … and have no mouth, anus, or gut. The females extend roots into the bones to tap the fats within. With roots to delve into the bone, a trunk of main body, and a crown of respiratory organs extending from the trunk, the flower moniker is appropriate. Perhaps that’s why one of the first named species got the Latin name of Osedax mucofloris, literally bone-devouring, mucus flower. The males? Female Osedax worms have harems of dwarf males, up to 114 in one species, that inhabit her trunk.

When whales die and sink to their watery graves, they bring to the seafloor bones rich in those fatty lipids. Thousands of bone-eating females, each just few millimeters high, will infest a whale carcass. So many will accumulate, the whale bones will appear to be covered in a circa 1970’s red shag rug-a rug that eats bones, has harems, and secretes acids, but otherwise a normal shag rug. Originally, and with good reason, it was thought that Osedax was clearly a whale-fall specialist. The core of whale bones consists of a matrix rich in lipids – up to 60 percent.

But what about something wholly different? Before the age of large marine mammals, large marine reptiles dominated the oceans. During the Mesozoic Era, rising to dominance in the Triassic and Jurassic periods, ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and nothosaurs represented a diverse group of large marine predators terrorizing smaller creatures in the dark depths. The ichthyosaur Shonisaurus may have reached lengths of up to 21 meters in the Late Jurassic and Plesiosaurus may been 12–15 meters in length. The ancient sunken carcasses of these massive marine reptiles may have hosted ancient Osedax. We do know that prehistoric ichthyosaur falls are known to support communities similar to modern whale falls.

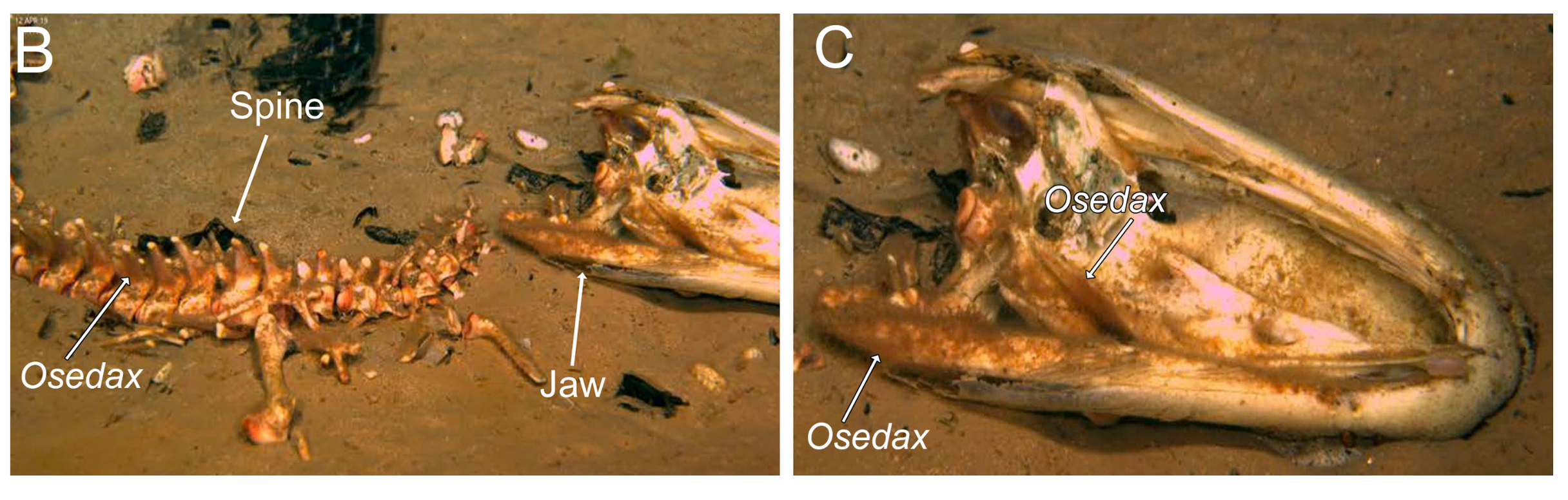

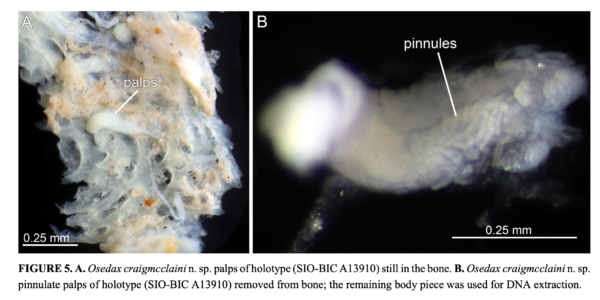

Not to be outdone by other scientists in throwing random things on the seafloor to see what will eat it, in early 2019 I placed not one but three dead alligators on the seafloor in the deep Gulf of Mexico. Alligators are nice modern analogues of the giant reptiles that once lurked in paleo-oceans and in my current state of Louisiana…well…readily available. And because we could, we place a packet of cow bones down there as well. 53 days later, my team and I visit the alligator carcass to find nothing but bones. The reddish hue of fuzziness on them indicates Osedax are present. On May 3, 2019, we overnight some of the collected bones out to California so Greg Rouse can inspect them in his lab and confirm their presence. We wait patiently for an email from Greg. On May 23, we get an email from him with the subject “Two new species :-)”. We are elated! Indeed, he finds females with well-developed ovaries and eggs. Using genetics, he determines that the Osedax on the alligator and cow bones are both new species, previously unknown to science.

Fast forward to today when I get an email with the subject “Your species”. That Osedax from the alligator is named after me.

Osedax craigmcclaini n. sp. is named for Dr. Craig McClain, an esteemed deep-sea biologist and colleague who led the experimental alligator fall project (McClain et al., 2019) and provided the Osedax specimens for this study.

New Species of Osedax (Siboglinidae: Annelida) from New Zealand and the Gulf of Mexico