The deep sea host a remarkably high diversity of life, a realm teeming with an astonishing array of species with a vast set of adaptations that allow them to survive in this inhospitable environment. However, the origins of this incredible biodiversity remain a compelling mystery.

The fossil record hints at a trend of shallow origins diversifying into the depths for certain marine organisms. However, conflicting results arise from approaches based on genetics, some supporting an onshore-offshore evolutionary pattern while others propose the opposite.

Enter the world of scleractinian corals, the stony or hard corals, a perfect testing ground for studying biodiversity across massive depth gradients. These corals span a wide depth range, from the ocean’s surface to depths surpassing 6,000 meters. How these creatures spread and settle in different areas, influenced by changes in their physical traits, help us understand the complex ways they’ve evolved over time and in response to the deep sea Take Micrabaciidae, a family of scleractinian corals. They have a slender, porous skeleton covered entirely by tissue—a probable adjustment for survival in the deep sea, where crafting a larger, sturdier skeleton becomes challenging due to lower aragonite, a form of calcium carbonate needed to build shells and skeletons, levels.

Half of the scleractinian corals form vibrant shallow reefs, while the other half, independent of the photic zone, thrives in cold waters across diverse regions and depths. This diversity not only paints a vivid picture of the coral world but also holds keys to understanding the origins of deep-sea life and diversity.

A new study by Campoy et al asks four key hypotheses about evolution of scleractinian corals

- Origin of these corals might trace back to the upper bathyal zone (200–1000 meters). The steep and varied nature of this zone creates distinct environmental conditions, potentially fostering diverse adaptations across depths and serving as a catalyst for biodiversity

- Lineages where symbiosis or coloniality emerged saw heightened rates of colonization. If these traits indeed bolstered the corals’ ability to spread, their emergence should align with faster colonization rates.

- A prolonged evolutionary trend favoring faster colonization toward shallower waters. This hypothesis assumes that the common ancestor of these corals lacked symbiotic relationships and lived solitarily, suggesting that symbiosis inherently links to the sunlit zones, with colonial species generally occupying shallower depths compared to solitary ones.

- Evolutionary forces predominantly shaping species’ depth ranges occur more significantly in shallower waters. As depth increases, environmental variability and interactions among species decrease, potentially slowing down the evolutionary pace through deeper zones.

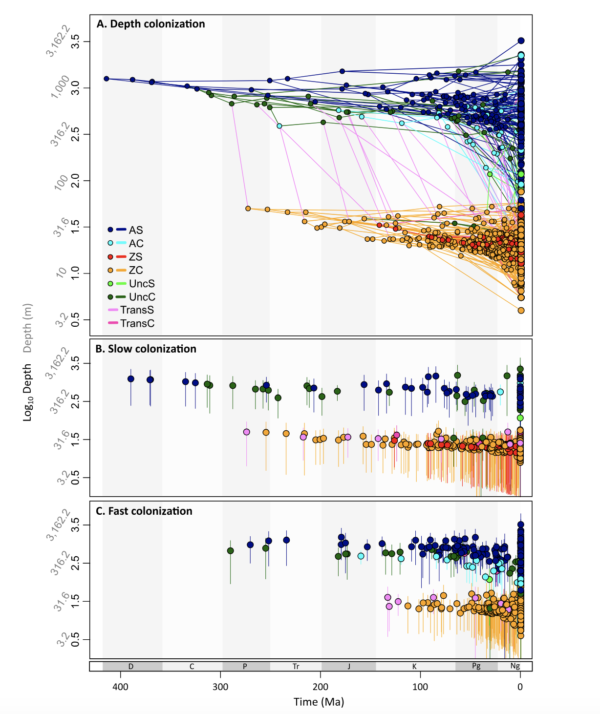

The intricate dance of evolution (too much?) reveals itself through deep-water origins, surviving multiple geological changes and even global anoxic events. Specifically, the results show that the order Scleractinia originated 415.8 million years ago somewhere between 229–2287 meters depth. The emergence of the Scleractinia order in the deep sea aligns with a pattern of evolution from offshore to onshore and not providing strong support for upper bathyal zone origination as in hypothesis one. However, various coral lineages spread and settled at varying rates across different depths. Moreover, the pace of colonization slows at greater depths, underscoring the vulnerability of these ecosystems to further and current human exploitation.

Campoy, Ana N., et al. “Deep-sea origin and depth colonization associated with phenotypic innovations in scleractinian corals.” Nature Communications 14.1 (2023): 7458.

Share the post "From Depths Unknown: Deciphering the Origins of Deep-Sea Biodiversity"