This story starts with my research team currently deploying alligators* (3 total, 2 – 2.5 meters in length) at three different sites 2000 meters deep in the Gulf of Mexico. The experiment is to examine the role of alligators in biodiversity and carbon cycling in the deep oceans.

Wait…what? What kind of mad science is this?

What you need to know is that the deep oceans, encompassing depths below 200 m, cover most of Earth and are especially food-deprived systems. Primary production of carbon is minimal only occurring through alternative pathways such as chemosynthesis. However, chemosynthesis is a tiny fraction of total ocean production (0.02–0.03%) and the energy that sustains most deep-sea organisms is sequestered in sinking particulate organic carbon derived from plankton hundreds of meters to kilometers above near the sea surface. At the abyssal seafloor, this sinking particulate organic carbon represents less than 1% of surface production.

This minimal amount of carbon available opens the door for more unique sources of carbon. Enter food falls and aligators.

The remains of large plants, algae, and animals arrive as bulk parcels that create areas of intense food enrichment. Deep-sea scientists have explored these food falls through both naturally occurring and experimentally deployed wood (#woodfall) and plant remains, cameras baited with animal carcasses, chance occurrences of and deployed intact whale carcasses several miles deep on the seafloor. These experimental and natural food falls have revealed the important role they play in deep-sea diversity. Many of these large food falls on the deep-sea floor, host highly diverse and endemic suites of organisms in

But why alligators? With regard to animal falls, prior work as focused primarily on whales and other cetaceans, pinnipeds, large fish such as tuna, and elasmobranchs. However, it very likely that marine reptiles both currently, and even prehistorically, are an important source of carbon in the deep oceans. Before the existence of whales, perhaps large marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, and plesiosaurs hosted diverse and endemic invertebrate communities on sunken carcasses, similar to modern-day whale

Alligator carcasses in the deep ocean are also not as nearly impossible as you might think. Both live individuals and carcasses of alligators are frequent on beaches and in coastal surf. A 3-meter individual came ashore at Folly Beach, South Carolina in 2014 and in 2016 a carcass of a 4-meter individual washed up on a beach in Galveston, Texas. These individuals of A.

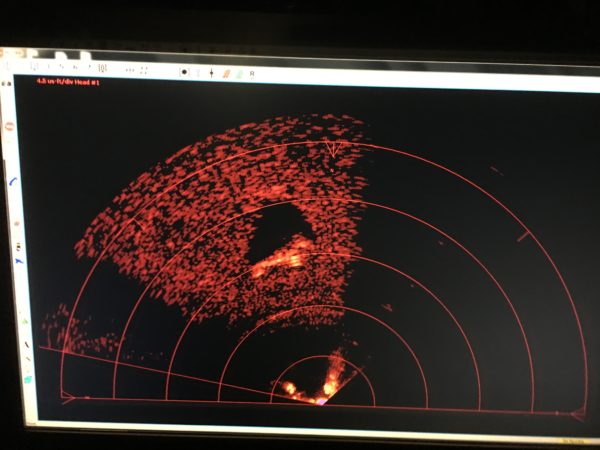

Thus, I am on ship, 100’s of kilometers from shore, placing an alligator 2 kilometers deep on the seafloor.

*The three alligators were culled by the state of Louisiana to control population numbers and in aid of restoration efforts. The alligator carcasses were then permitted to us for scientific use. The conservation and any taking of alligators in Louisiana is a very serious and thorough process. You can read more about the conservation success story that is alligators in Louisiana here https://t.co/LQskiPyg6e.

While it’s true gators have sometimes been spotted at sea and on marine coasts, you could also just point to them as analogs for the saltwater crocodile. They’re probably roughly nutritionally equivalent, and salties routinely not only move along coasts and between islands, but swim hundreds of miles across open ocean, and vagrants have turned up in Fiji, Iwo Jima, the Marshall Islands, the Maldives, and Japan. American crocs also seem comfy moving up and down the coasts, though they don’t have the reputation for long voyages like salties.