Photo: Cpl. Jo Jones [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The Background

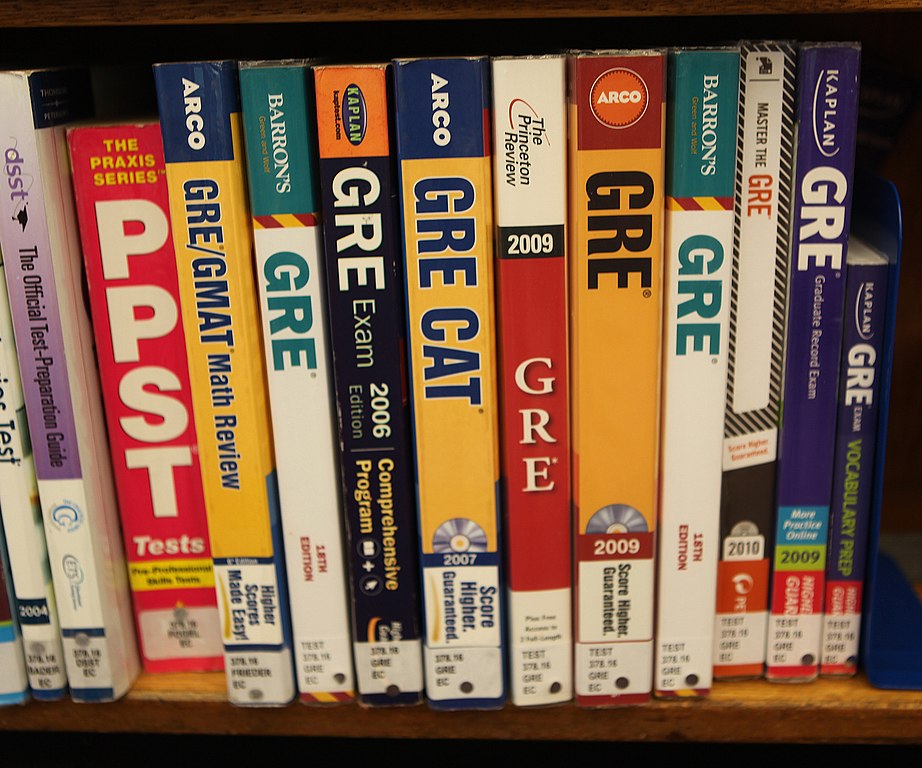

Most of you are probably aware of the GRE or Graduate Record Examination. Those applying for graduate programs are required to report scores from this standardized test. The GRE, along with the resume/curriculum vitae illustrating depth and breadth of experience, GPA, letters of recommendation, and an essay are evaluated for acceptance into many graduate programs. Although the weight given to the applicant’s GRE varies among institutions, many schools and departments require the GRE and set minimum scores for application/acceptance. Typically top institutions and programs institute a high minimum GRE score to reduce the number of applicants and to ensure highly accomplished applicant pools. However, to what extent does the GRE predict success in graduate school? Does the GRE accurately measure an applicant’s ability to synthesize and apply knowledge, acquire and assimilate new information, or familiarity with mathematics, vocabulary, biology, history, chemistry, etc.?

Criticisms of the GRE

Critics of the GRE, myself included, feel that the GRE does not evaluate any of these but simply provides a metric for how well a person can master GRE test-taking procedures. ETS, the nonprofit that administers the test, states “the tests are intended to measure a portion of the individual characteristics that are important for graduate study: reasoning skills, critical thinking, and the ability to communicate effectively in writing in the General Test, and discipline-specific content knowledge through the Subject Test” However, the Princeton Review guide states, “ETS has long claimed that one can not be coached to do better on its tests. If the GRE were indeed a test of intelligence, then that would be true. But the GRE is NOT [emphasis original] a measure of intelligence; it’s a test of how well you handle standardized tests.” Indeed, training for the test, either in a GRE course or with a book, involves more learning test-taking strategies rather than a focus on acquirement or application of specific knowledge, i.e. “cracking the system”. Before the days of computerized exams, more math questions were included on the test than the average mathematically literate undergraduate could solve in the designated time period. To prep for the math section of the GRE, I and others learned not geometry or algebra, or even logic, but rather methods, i.e. cheats or tricks, to quickly move through the question. Of course, these tricks provide little help when math is encountered in either academia or the real world.

Who evaluates and writes the questions on the GRE? The Princeton Review states “You might be surprised to learn that the GRE isn’t written by distinguished professors, renowned scholars, or graduate school admissions officers. For the most part, it’s written by ordinary ETS employees, sometimes with freelance help from local graduate students.” Unfortunately, I am not able to retrieve information about question writers online either from ETS or other sources, so there is little I can comment on. However, the lack of transparency and accessible information should give all of us pause.

I am from the old guard and took my GRE with a No. 2 pencil with which I spent hours incessantly filling little circles. Modern tests are computerized and use a computer-adaptive methodology. Simply, the difficulty of questions is automatically adjusted as the test taker correctly or incorrectly answers questions. A complicated formula is used based on the level of questions and how many you answered correctly to determine your “real GRE score”. There is a substantial criticism of the computer-adaptive methodology. One, if a test taker suddenly encounters an easy question mid-exam, they may deduce they have not been performing well thereby affecting their performance through the rest of the exam. Test takers may also be discouraged if relatively difficult questions are presented earlier on. Second, unequal weighting is given to questions, with earlier questions receiving more and setting precedent for later questions, biasing against test takers who become more comfortable as the test continues. ETS is aware of these issues. In 2006, they announced plans to radically redesign the test structure but later announced, “Plans for launching an entirely new test all at once were dropped, and ETS decided to introduce new question types and improvements gradually over time.”

The GRE, a financial burden for students.

The GRE is expensive to take, $160 per test for U.S citizens. Most students will take it at least twice to try to get their score higher. This encouraged by both academia and ETS. If you buy GRE prep books, which is also encouraged, you could easily be out another $100. At the minimum, a student is putting out $420.

It is often encouraged that the prospective graduate student also takes a GRE prep course. I will use Kaplan as an example, but there are others.

- In person course $1,299 or in person plus $1,699 (link)

- Life online $999 or live online plus $1,399 (link)

- Tutor $2,499 (link)

By the time you count in missed work hours for test taking and preparation, transportation to the test (mine was 1-hour from my college), and various other expenses, a student could easily be out a significant amount of money. It is also an additional $27 to have your own GRE test scores sent to more than the 4 “free” schools that come with the test.

So is the GRE finding us the best students or simply the richest?

Educational Testing Services: a multinational operation, complete with for-profit subsidiaries

So who is ETS? They are a nonprofit 501(c)(3) created in 1947, located in Princeton, New Jersey. In an article from Business Week…

”Mention the Educational Testing Service, and most people think of the SAT, the Scholastic Aptitude Test that millions of high schoolers sweat over each year in hopes of lofty scores to help ease their way into colleges. But if ETS President Kurt M. Landgraf has his way, Americans will encounter the testing giant’s exams throughout grade school and right through their professional careers. Landgraf, a former DuPont executive brought to the organization in 2000 to give ETS a dose of business-world smarts, has a grand vision for the cerebral Princeton (N.J.) nonprofit. Worried that the backlash against college testing means a lackluster future for the SAT and other higher-ed ETS exams, Landgraf has been trying to diversify into two growth markets: tests and curriculum development for grade schools, where the federal No Child Left Behind Act has spurred national demand for testing, and the corporate market, where Landgraf sees potential growth in testing for managerial skills. By 2008, he hopes expansion in these two areas will more than double ETS’s $900 million anticipated 2004 revenue. “My job is to diversify ETS so we are no longer reliant on one or two major tests,” he says.

Does this sound like language applied to a nonprofit? From the New York Times…

It has quietly grown into a multinational operation, complete with for-profit subsidiaries, a reserve fund of $91 million, and revenue last year of $411 million… Its lush 360-acre property is dotted with low, tasteful brick buildings, tennis courts, a swimming pool, a private hotel and an impressive home where its president lives rent free… E.T.S. has come under fire not only for its failure to address increased incidents of cheating and fraud, but also for what its critics say is its transformation into a highly competitive business operation that is as much multinational monopoly as nonprofit institution, one capable of charging hefty fees, laying off workers and using sharp elbows in competing against rivals… ”E.T.S. is standing on the cusp of deciding whether it is an education institution or a commercial institution,” said Winton H. Manning, a former E.T.S. senior vice president who retired two years ago. ”I’m disappointed in the direction they have taken away from education and public service.”

In response to growing criticism of its monopoly, New York state passed the Educational Testing Act, a disclosure law which required ETS to make available certain test questions and graded answer sheets to students.

For all practical purposes, ETS has grown into a for-profit institution trading on its nonprofit status to create a monopoly (read the New York Times and Business Week articles for more alarming revelations). For example,

- As of the Spring of 2018, 24,141 graduate students were enrolled as graduate students in Louisana.

- Let’s assume that the applicant pool into Louisiana graduate programs was 2:1 (they are probably considerably more competitive), so 48,282 applicants took the GRE.

- At $160 per test (its actually $190 for non-US students), that generates $7,725,120 for just the current body of graduate students.

- If we assume the near 50,000 applicants represent the cumulative applicants over a typical 5 years Ph.D. program, i.e. represent multiple cohorts, then ETS generates conservatively $1,545,024 per year from Louisiana alone.

In 2016, ETS brought in $1,609,201,000 dollars in revenue. You read that right. One. Point. Six. BILLION. Dollars. Most of that revenue, over 97% comes directly from testing. You can find the complete financials from 2016 backward at ProPublica. ETS also markets through one of their subsidiaries, and for-profit, a test book at $33.89 (at Amazon). “We prepare the tests-let us help prepare you!” It is unclear the total revenues these subsidiaries bring in.

The GRE does not predict success in graduate school

But what of the original question? To what extent does the GRE predict success in graduate school? A meta-analysis in 2001 by Kuncel et al. demonstrated that correlations between GRE scores and multiple metrics of graduate performance were low. Correlation with graduate GPA ranged from 0.34-0.36. With performance as evaluated by departmental faculty the correlation ranged from 0.35-0.42, time of degree completion ranged from -0.08-0.28, citation count ranged from 0.17-0.24, and degree attainment from 0.11 to 0.20. While encouraging these correlations are positive (in most cases) and even accounting that GRE is supposed to be evaluated in the context of other materials (but often are not), these correlations are not that impressive. Do we need the GRE scores to evaluate applicants? Interesting, the same study also demonstrated that undergraduate GPA performed equally well as the GRE.

Even [ETS], warns that there’s only a tenuous connection between test scores and success in graduate school. According to the ETS report, “Toward a Description of Successful Graduate Students,” “The limitations of graduate school admissions tests in the face of the complexity of the graduate education process have long been recognized.” The report acknowledges that critical skills associated with scholarly and professional competence aren’t measured by the GRE… Perhaps more alarmingly, as with the SAT, high GRE test scores time and again tend to correlate with a student’s socioeconomic status, race, and gender. Research dating back decades from the University of Florida, Stanford, New York University, the University of Missouri, and ETS has shown that the GRE underpredicts the success of minority students…ETS studies have also concluded the GRE particularly underpredicts for women over 25, who represent more than half of female test-takers. [link]

Death to the GRE

In recap, the GRE is a financial burden to students, poorly predicts graduate student success, and has biases associated with socioeconomic status, race, and gender with profits going to a $1 billion revenue “nonprofit” company. It is abundantly clear, we need to rid academia of the GRE. Thankfully, I am not the only one to believe this. Two physics professors in op-ed in Nature (open-access) called for the same.

This is a call to acknowledge that the typical weight given to GRE scores in admissions is disproportionate. If we diminish reliance on GRE and instead augment current admissions practices with proven markers of achievement, such as grit and diligence, we will make our PhD programmes more inclusive and will more efficiently identify applicants with potential for long-term success as researchers.

As well as the President of the American Astronomical Society,

It’s a matter of great concern to all of us: failing to draw from the full pool of talent weakens our profession. It’s vitally important to train leaders who will help our profession achieve true equity and inclusion, and thus the strongest possible astronomical community.

In a bold move shortly after, the American Astronomical Society adopted a policy to encourage departments to make the GRE optional or to stop using it. What has followed is a wave of schools and departments dropping GREs (link, link). Joshua Hall, Director of Admissions at UNC (on Twitter @jdhallphd) maintains a list of all biology and biomedical programs who have dropped GREs from the applicant process.

Your next step? If your department, school, and university still use the GRE, it is time to call the faculty together and kill the GRE.

UPDATE 1: Follow the #grexit hashtag on Twitter

It’s a tool. One of many used to help predict readiness for a PhD progam not completion. There are many factors that lead people to leave a program including job opportunities, other life choices, and finances. If it doesnt answers to the particular PhD program, then they should be relying on better data but obviously there is a question answered from this exam that is somewhat useful. Perhaps financial aid would be helpful for subsidizing the test.

I owe you my life for this info!!!

God bless <3

Thanks very much for this article!

You might be interested in our new publication: Multi-institutional study of GRE scores as predictors of STEM PhD degree completion: GRE gets a low mark. We studied 1805 STEM doctoral students in 4 state flagship institutions and found that GRE scores did not predict PhD completion, time to degree or the likelihood of dropping during or after the first year for women. For men, those with the LOWEST GRE Q scores (34th percentile) completed degrees at a significantly HIGHER rate than men with GRE scores in the 91st percentile. The pattern held for all four institutions and for engineering students. The paper can be found at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0206570

Our website beyondthegre.org gives other reasons for why we should get rid of the GRE.

I took the GRE in the early 90s without any preparation and pretty much smoked it. I figured it was supposed to test what I knew, not what I could cram. As it turned out, the graduate program I entered didn’t use the GRE, for much the same reasons given in the article.

There has to be some way to compare applicants from different universities.

A Caltech student who is taking graduate level courses his senior year and who has only a 2.9 GPA is a much better candidate than a Cal State LA graduate taking easy courses and has a 4.0.

The alternative of taking each course each applicant takes and trying to adjust the grade to some standard based on level of difficulty is impractical, misguided, and would result in many errors.

Could an alternative test be developed? Sure. But in the meantime, we have what we have.

The way to fix one insufficient metric is not by adding another poorly devised one. Also, it is quite clear the GRE does not measure success or performance in any concrete way. This is why GPA is only one metric considered. This is also why research experience, extracurricular activities, letters of recommendation, and personal and research statements are also evaluated. What is clear is that the GRE provides no defendable or evidenced measure of the quality of the candidate, particularly in those skills that determine success in graduate school.

In addittion, I don’t believe it is completely fair to assume that a low GPA may reflect the reputation of some institutions of being “inferior” in rigor to others. Indeed, discriminating against a student from a state or regional college/university who has excellent GPA for not attending an ivy league school (something that may not have been affordable) is something I will not engage in. Plus grade inflation at some ivy league schools is well known https://www.vox.com/xpress/2014/9/10/6132411/chart-grade-inflation-in-the-ivy-league-over-time.

I have been on graduate admissions committees for too many decades to think about. As well, I will this coming year produce my 40th and probably last graduate student. And for the record, I did take the GRE before grad school, including the advanced biology test, and did very well, including the math section even though I had failed calculus as an undergrad. Who knows what the hell the test was measuring, except that as Dr. M noted, I did have math shortcuts figured out so came within 5 questions of finishing the test. I think that was all due to my fabulous Canadian education…. ha!

My long experience with this test has suggested to me that it is at best a low level indicator of ability to solve problems or of general knowledge. I have often had to fight as a member of the admission committee to admit a student with low scores even though their GPA was high and their letters were very encouraging. On the flip side, we have admitted over the years a bunch of students with very high scores, high GPA, letters that suggest the student will be the most incredible biologist ever, but in the end some of those students drop out after a year or two. None of these things measure drive and creativity.

For my own students, as an example of my approach, I took into my lab for a phd a student who was in his 30s, had a degree in piano theory from a great music school, then toured Europe playing the piano in hotel lobbies, and who knows what else. I took him because he had drive and I thought his music background would portend some strong creativity. I wasn’t too far off the mark. He finished his phd in 4 years and has been gainfully employed every since. I can tell similar stories for other students. It has always been the personal interview that has influenced me. I would never take a student without that.

I never needed the GRE. I think it is a crutch and administrators love it because it gives them numbers. At my university, when the admission process is done, the admin publishes across the campus a list of admissions by department, how many applicants there were, and the mean GRE scores among other “metrics.” What could be better than some numbers on a spreadsheet. So they really don’t like it when I say I have this great student from some small island who never heard of the GRE….

The GRE demonstrates that a student can show up on time with a pencil, concentrate for 2 hours while not creating a fuss – all good to know about a prospective student at an level.

I am on board for eliminating all standardized tests as admission factors. Let the student’s body work and their communication skills determine if they are qualified for any particular institution. I make my secondary and college students create portfolios that they can share with the universities they apply to in determining their worth.