Guest Post: This past winter my good friend and excellent nature photographer Michael Ready and I were out exploring the Rocky Intertidal zone at Cabrillo National Monument in San Diego, Ca. While perusing through the rocky outcrops I happened upon a group of Hopkin’s Rose nudibranchs (what does one call a group of nudibranchs anyways?) Beyond seeing more than one of these squishy denizens of the not-so-deep in a little clump, they were also accompanied by their bryozoan food and a couple of neat little pink egg rings. I HAD NEVER SEEN THEIR EGG RINGS BEFORE!! SO COOL!! Anyways, Mike snagged some excellent pics and wrote a little ditty about it to share with the people. (Note: This is cross posted on our field blog, Cabrillo Field Notes). Enjoy the cool natural history of it all!

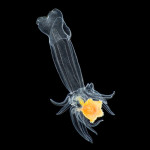

The shell-less gastropods of the sea are collectively known as “sea slugs”. A well-known subgroup of these mollusks, the nudibranchs, are among the most colorful and captivating creatures in the ocean. Nudibranch (noo-də-bránk) means ‘naked-gill’, referring to their external filamentous respiratory organs; one of the physical characters that distinguishes them from other sea slugs. “Nudis”, as they are affectionately called, are also a quite successful clan. Over 2000 are species are known to inhabit marine environments around the planet, from the extreme depths of the seafloor to the littoral pools of the intertidal zone.

The waters of Cabrillo National Monument host at least 25 different species of these soft bodied jewels, a few of which may be observed during a good low tide. With the right timing and a keen eye, one can pick out the small but unmistakable Hopkins’ rose nudibranch (Okenia rosacea). They are one of the more common nudibranchs found here and perhaps the least inconspicuous of all the tidepool organisms at the park. Though small–only 2-3 centimeters long–it’s hard to miss their bright pink, frilly papillae swaying in the water.

The rose nudibranch was first described in 1905 by Frank Mace McFarland, a marine biologist from Stanford University and one of the founders of Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, California. McFarland, well known for his contributions to malacology (the study of mollusks), originally named the rosey-colored slug ‘Hopkinsia rosacea’ after his friend and patron of the marine lab, Timothy Hopkins.

Rose nudibranchs are carnivorous. They utilize their sensory organs, known as rhinophores, to locate their sole food source: the pink encrusting bryozoan, Integripelta bilabiata. They then extract the bryozoan’s soft tissue with specialized teeth. Like many nudibranchs, Okenia rosacea steals the toxins and calcareous spicules of their prey and place them into their feathery appendages for protection. In addition to nourishment and protective compounds, these nudibranchs garner their stunning color from their bryozoan food. The tissues of the bryozoans contain hopkinsiaxanthin, the compound responsible for the slug’’s intense pink hue; and a carotenoid that was unknown to science before its discovery in the tissues of these species.

Historically, the range of these nudis extends from Northern Baja California, Mexico up to the lower Oregon coast. But, until recently, they were rarely noted north of San Francisco. Over the last few years, however, Hopkins’ rose have been seen in surprisingly high numbers in parts of Northern California and have even been observed spawning in the coastal waters of Southern Oregon, a locality in their range that was previously only known from only one specimen. Researchers believe this shift may be due to a warm water anomaly occurring in the North Pacific in 2014 and find it indicative of warming climatic conditions in general.

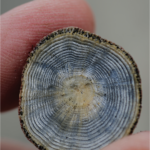

Like other nudibranchs, Okenia rosacea is a simultaneous hermaphrodite. Equipped with both male and female reproductive organs, this species can mate with any other mature individual of the same species. The mated slugs will deposit their pink, ribbon-like spiral egg masses on rocks and other tide pool substrates. In the act of spawning, they deposit eggs from the outside working inward in a counterclockwise motion, thus creating a clockwise spiral. From the eggs hatch tiny planktonic larvae, which develop and eventually settle on the substrate to grow to adulthood.

The more you look into it, the more there is to learn about these bright, beautiful, and fascinating mollusks. The same can be said of just about any species. Our National Parks hold multitudes of life forms, each with myriad complexities and adaptations to discover.

The next time you are exploring the rocky intertidal of the California (or Oregon!) coast, keep an eye out for the truly splendid Hopkins’ rose.

Sources and Reference:

Bertsch H. “Life history of the intertidal Californian nudibranch Hopkinsia rosacea MacFarland, 1905”. Western Society of Malacologists, Annual Report, 1989 21:19-20.

Emerson, W. K., Morris, Robert H., Donald P. Abbott, and Eugene C. Haderlie. “Intertidal invertebrates of California” Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. 1980 98,326

Goddard, Jeffrey H. R. Treneman, N., et.al , “Nudibranch Range Shifts Associated with the 2014 Warm Anomaly in the Northeast Pacific”, Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences 115(1). 2016 :15-40

Strain H. H. “Hopkinsiaxanthin, a xanthophyll of the sea slug Hopkinsia rosacea”. Biological Bulletin97(1) 1949 :206-209.

I think a group of these would be called a bouquet!

A group of them should be called a nudi colony