This is a guest post by friend and colleague, Dr. Tara Whitty. Dr. Whitty is currently a NSF SEES Fellow and Conservation Assessment Scholar at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography’s Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation (CMBC). Though I don’t normally run in the same circles as dolphin researchers, Tara is my one big exception. Her work is on the forefront of interdisciplinary investigations between small-scale fisheries, conservation, and community-based management. Dolphins just happen to be in the middle more often than not. You may recall a previous DSN article highlighting her doctoral research on The Plight of the Irrawaddy. As if that wasn’t challenging enough, Dr. Whitty has since set her sights on the poster child of Issues in Marine Mammal Conservation – The Vaquita.

Threats of international boycotts. A conservation activism group’s boat burned in effigy. Government vehicles overturned by angry citizens. A cartel trafficking illegal wildlife goods worth thousands of dollars per kilo.

At the heart of this? An adorable porpoise – the vaquita, sometimes called the “panda of the sea.” It is the world’s most endangered marine mammal, occurring only in the Upper Gulf of California and threatened by bycatch in gillnets in local small-scale fisheries. Its fate is inextricably entangled (ah, bycatch puns) in a complex mess of human motivations and actions.

This high-profile conservation issue has drawn millions of dollars and decades of hard work by some of the world’s brightest and most dedicated minds. Yet we’ve reached a point where desperate, high-risk efforts to catch and keep vaquita in captivity is the only option for this species’ survival (here is a not particularly great, but widely read, piece in the NYT). How did this happen?

Well, one thing to consider is that there is a critically important group of players that are not represented in most media stories on this issue: the local communities. These include people now unable to feed their families, and worried about increasing rates of drug addiction and crime. People who feel disenfranchised and villified and misunderstood. Numerous colleagues and I believe that this sector has been disregarded not only in media coverage, but also in decision-making, in a way that is ultimately counterproductive to conservation (not to mention human well-being).

My insights are based on a recent research project that I co-developed: “Stakeholder perspectives on the future of vaquita conservation.” With guidance from experts, my fantastic research team and I interviewed fishers and community members in San Felipe and El Golfo de Santa Clara, as well as conservation groups, researchers, and government agencies about their perceptions regarding vaquita conservation.

Given the heated nature of this topic, some fine print: These ideas do not necessarily represent the views of anyone besides me. This post presents a *very* simplified version of our project and the system. Our findings are based on what people chose to tell us – truths, deliberate non-truths, or inadvertent non-truths. Even though these might not be absolute fact, people’s perceptions are critically important.

The system

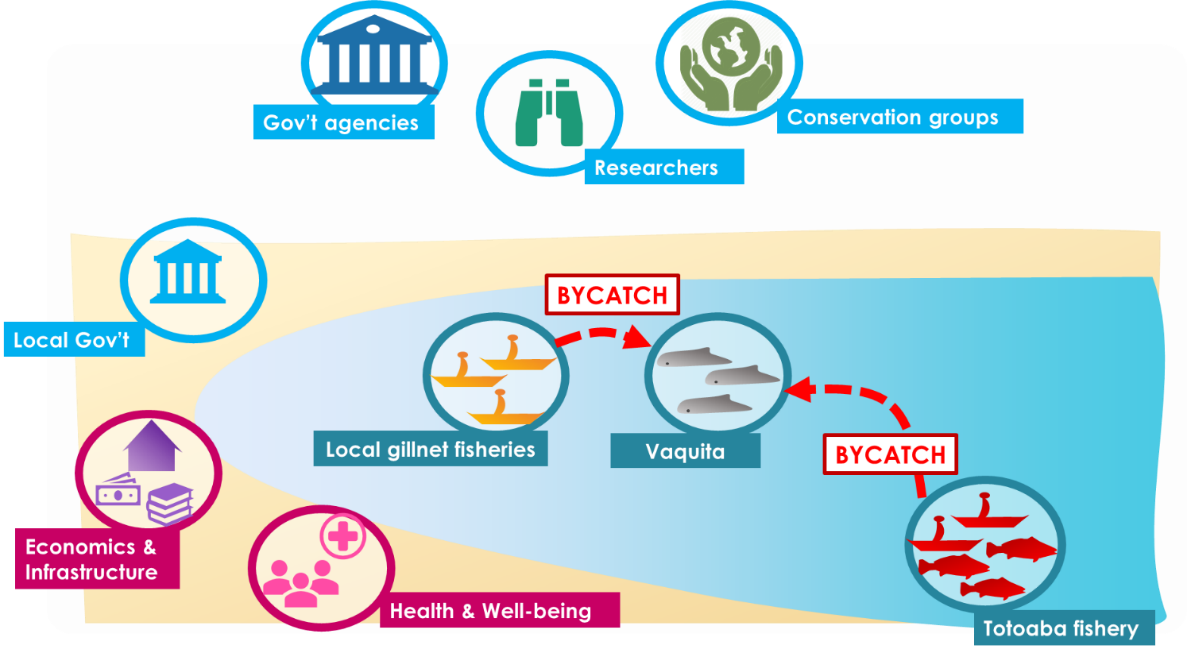

At the interface between small-scale fisheries and conservation, it is especially critical to understand the elements and interactions between human society and nature. So, what does the vaquita conservation system look like? Below is a (simplified) version of the entities involved:

At the heart of the system? The vaquita, local fisheries, and the illegal fishery for totoaba, a fish whose swim bladders sell at staggeringly high prices to Asian markets. This is run by cartels (one of my field assistants – somewhat jokingly – said, “Tara, please don’t get us killed”).

At the heart of the system? The vaquita, local fisheries, and the illegal fishery for totoaba, a fish whose swim bladders sell at staggeringly high prices to Asian markets. This is run by cartels (one of my field assistants – somewhat jokingly – said, “Tara, please don’t get us killed”).

The infrastructure and economics of local communities, as well as the health and well-being of community members, heavily influence the feasibility of transitioning from a gillnet-based economy. The system includes how these fisheries and communities are managed, i.e. by government agencies (local and national), as well as conservation groups, and researchers who might be affiliated with government agencies, conservation groups, or academia.

These groups dynamics are complex. For example, fishers might belong to cooperatives, organized into federations. The perspectives of a cooperative leader will differ from those of a fisher who works on a boat that someone else owns. There are also independent fishers who do not belong to cooperatives. Furthermore, different priorities exist within the government agencies, researchers, and conservation groups. Some focus more on fisheries, others more on vaquita conservation. This sets the stage for conflict not only among different stakeholder groups, but also within.

The “solution”

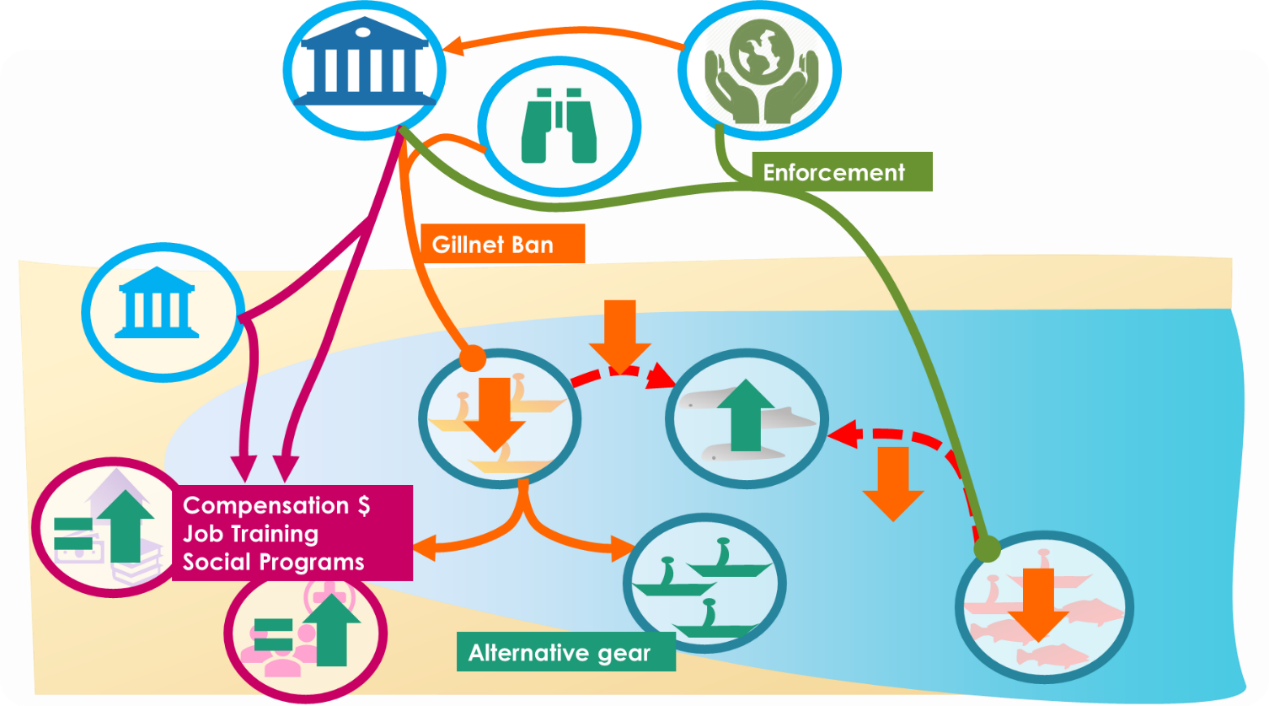

As an emergency effort to save this species, conservation groups pushed for a 2-year gillnet ban from 2015-2017. This ban was accompanied by a compensation scheme for fishers who would be losing their livelihood. Additionally, social programs were promised to assist in transitioning to alternative livelihoods. At the same time, trials were being run for “el chango ecologico,” a small, apparently environmentally-friendly, trawl. This vaquita-safe gear would be the proposed alternative gear for local fishers. Additionally, enforcement efforts again the totoaba fishery were stepped up, by the Navy and Sea Shepherd.

This is my doodle rendition of the plan – with anticipated reduction of bycatch and totoaba fishing, recovery of the vaquita, and limited negative impacts (perhaps positive impacts) to local communities:

So…how did it go?

Well, not as hoped:

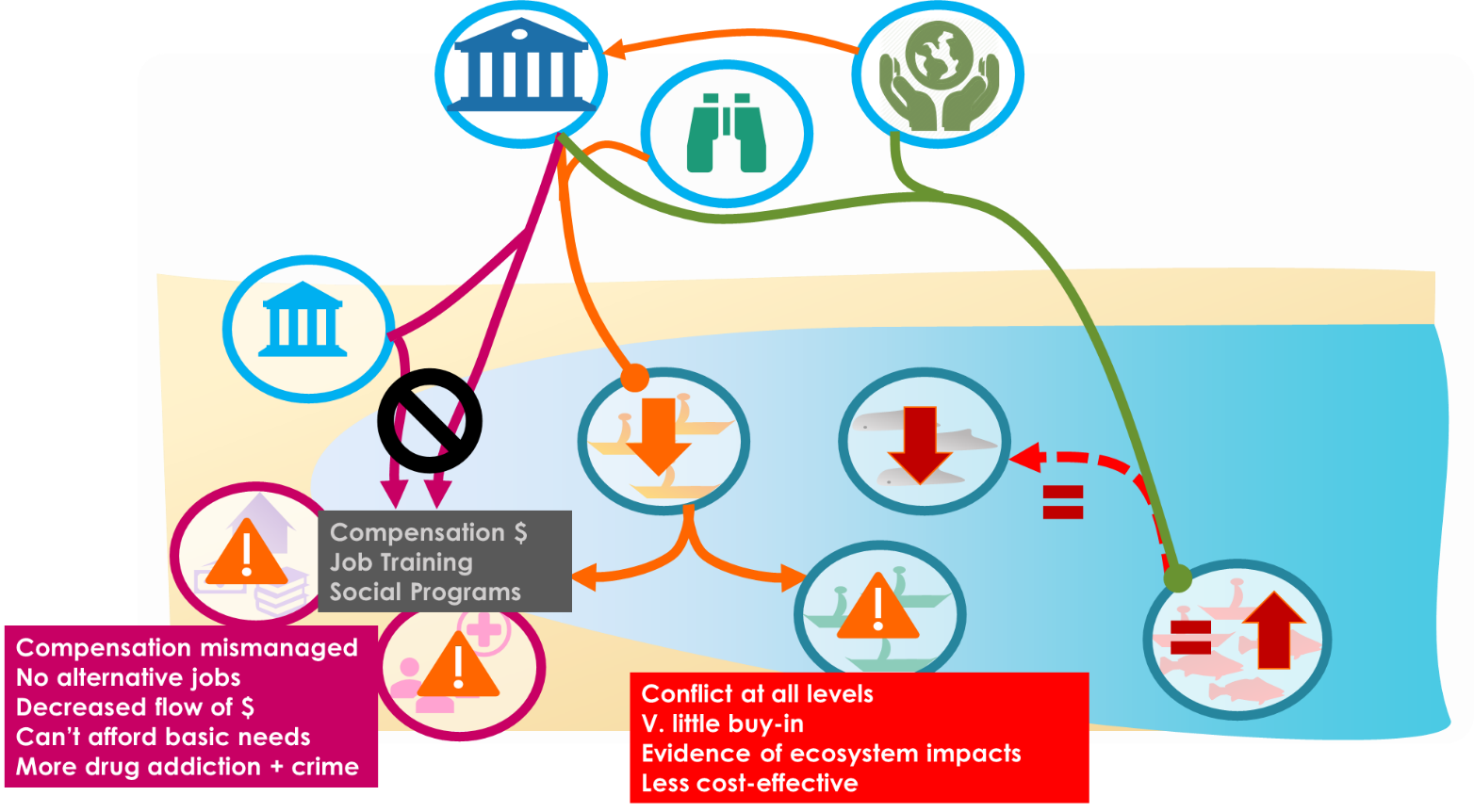

Vaquita bycatch continues, with the population dropping to a downright grim 30 individuals. The illegal totoaba fishery continues (and possibly has increased). And conflict between communities and conservation groups has grown even more heated.

The compensation program was mismanaged such that many fishers are not receiving it; no social support programs materialized; and many community members reported serious degradation in community and individual well-being. There was mention of some fishers entering the illegal totoaba fishery as the only feasible livelihood option.

The alternative gear is widely rejected by fishers, who state that it difficult and costly to use, inefficient, and damaging to the environment (more on this in a recent paper by Aburto-Oropeza et al. in Conservation Letter, summarized here). There is a daunting level of distrust between various groups involved in these trials.

All of this occurs on a long-standing foundation of conflict between stakeholders (e.g., Cisneros-Montemayor and Vincent 2016) . Some community members stated that the vaquita is a myth invented by conservationists; that bycatch does not occur in their gillnets; that data related to this are faked. Even those with more moderate beliefs expressed dismay about the lack of communication and inclusion by researchers and conservation groups. However, researchers firmly and exasperatedly emphasized to me that they had tried to share their research and findings. Clearly, there is a disconnect here. Even though information has been shared, it has not been effectively received – for whatever reason.

On a certain level, the solution to bycatch seems to be fairly simple: reduce the overlap between gillnets and the animals of concern. Of course, bycatch does not occur in isolation. Not to belabor the “bycatch pun” angle, but bycatch is generally tied up in complex systems of interconnected strings and knots. Any attempt to disentangle the situation will involve pulling on certain strings, which are connected to other strings and knots. In other words, each action will introduce tensions to other parts of the system. If these tensions are not anticipated and managed, the whole tangle might just become more intractable.

The ban added tension to an already-complicated series of intertwined knots. It pulled on the complex interconections between gillnet fisheries and community well-being, and at the particularly intractable knot linked to the totoaba fishery. Without a series of effective, concerted efforts to untangle these knots, this added tension has only made these knots more tight.

Narratives

Problems are easier to think about in simple terms. A bad side, a victim, and a good side. Evil, greedy corporations despoiling the earth for their own gain make for a storyline with limited moral ambiguity. This is an easy way to communicate a problem to the broader public.

Unfortunately, many conservation problems simply do not fit into this narrative. They are the products of complex systems – they are “wicked problems” (see Jentoft and Chuenpagdee 2009 on how this term applies to fisheries and coastal management) They make our heads hurt and force us to consider tricky ethical dilemmas.

So, it’s not surprising when a complex problem like vaquita bycatch becomes oversimplified in media coverage. Narratives that thoughtfully share the community side of this story are rare. The considerable impacts of the gillnet ban on their incomes, health, and well-being have not been widely covered. And though the NYT story and others convey otherwise, most of the fishers and community members we interviewed had positive perceptions of the vaquita – viewing it as a beautiful animal that had a right to exist, that was a part of their natural heritage. Their objections were to conservation approaches that harmed their communities, but they were generally supportive of the idea of conserving the vaquita.

Community members are tired of being villified. Many of them feel that their communities also suffer from the totoaba fishery and related influence of cartels; they feel attacked from all sides, by the cartels and by the conservationists. While some community members have engaged in aggressive protests, there are others who feel that these actions do not represent their community in a favorable light – yet these are the actions grabbing headlines.

A shift from the simple “bad guy, good guy” narrative could promote greater demand and support for holistic and, one imagines, more effective approaches. Some key recommendations from our interviewees include: truly effective communication about research methods and findings; inclusion of communities in research and decision-making, including the search for alternative gears other than the chango ecologico; cooperative, community-inclusive efforts to combat the totoaba fishery, improve infrastructure, and develop job training and alternative livelihoods; and broadening the focus of vaquita conservation to include other aspects of the ecosystem and the needs of communities, as articulately argued for in two recent papers (Cisneros-Montemayor and Vincent 2016; Aburto-Oropeza et al. 2017).

Of course, easier said than done. And it’s very easy to criticize as an outsider looking back on past actions. However, with greater demand for these types of solutions, I hope that there will be more research on how to meaningfully design and implement these recommendations rather than having them be the “ta-daaah, we’re finished here!” final section of reports and papers.

What now?

The solutions indicated by our research are long-term efforts to effect holistic change in the system. These are not last-ditch, emergency measures. So, while conservation and research groups mobilize to save this species through captivity, what else can be done?

You might have seen calls on social media to boycott seafood from Mexico. Supporting a boycott is a personal decision, and not necessarily a bad one. I would be loathe to support a market linked to vaquita bycatch. But I’d urge you to carefully think: what happens with this boycott? What strings does that pull on, and what tensions might be worsened? Would this spur the government toward more effective conservation action, toward more effectively controlling the totoaba trade? Are there plans to ensure that communities do not bear the burden of a problem that isn’t necessarily their fault? I’d like to see those calling for boycotts to also call for complementary efforts to work with communities as partners, rather than opponents.

What else can be done? There are at least two major opportunities:

- Invest in long-term social and environmental sustainability in the Upper Gulf beyond vaquita conservation, and involved the community in a more open, participatory approach to developing and designing creative, appropriate solutions for greater social and environmental well-being;

- Take these hard-earned lessons from the vaquita mess and apply them to similar conservation problems globally, that do not have the amount of publicity or funding that have been showered upon the vaquita. Unfortunately, marine mammal bycatch is a global issue, and we need to evaluate all attempts to solve this problem.

I was hoping to think of a humorous, catchy title for this post – for example, “Conservation at Cross Porpoises.” But that felt flippant in the face of this all-around depressing situation: a species will almost certainly soon be extinct in the wild, communities have suffered, scientists and conservationists have worked their hearts out, and the only obvious “bad guys” continue to reap the benefits from the illegal totoaba trade. My hope is that we can start to appreciate the complexity of these situations, and design strategies that match and adapt to this complexity for other cases.

—

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sincere “thank you” to all who participated in these interviews and to the communities of San Felipe and El Golfo de Santa Clara; to collaborator Samantha Young @ San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research and research team Areli Hernandez and Veronica Vargas; to the Gulf of California Marine Program. Research funded by NSF SEES Fellowship and SeaWorld Busch Gardens Conservation Fund.

REFERENCES

Aburto-Oropeza O, López-Sagástegui C, Moreno-Báez M, et al. 2017. Endangered Species, Ecosystem Integrity, and Human Livelihoods: Species conservation humans ecosystems. Conserv Lett.

Cisneros-Montemayor AM and Vincent AC. 2016. Science, society, and flagship species: social and political history as keys to conservation outcomes in the Gulf of California. Ecol Soc 21.

Jentoft S and Chuenpagdee R. 2009. Fisheries and coastal governance as a wicked problem. Mar Policy 33: 553–60.

Share the post "Beyond drug lords and conservationists: Who is missing in the coverage of the vaquita’s demise?"

Thank you for the educational downer.

Is there anything particularly special about these swim bladders versus others, to the people making soup? Could we research how to counterfeit them from non-endangered swim bladders? I guess at those prices people must be trying that plenty…

Would it be crazy for donors to subscribe like “$1 per vaquita, annually” to go to programs benefiting the fishermen and people who live in the area? Would they be able to apply social pressure or are there outside groups too involved? This plan would be tough on the scientists doing the population estimate.

Great post. Given that cartels are involved I think US drug policy has to bear some major responsibility for the extinction of the Vaquita.

(As a person of Chinese heritage…) I had a relative recently come back from Mexico, providing gifts of swim bladders. At the time, the thought running through my head was, “what an odd place to acquire swim bladders”. She said the quality was quite high, but beyond that, I don’t know what makes it special. And to be clear, I don’t think anything in the article says that the fish themselves are endangered…just that the method of catching them affects an endangered bycatch species.

I do want to thank Dr. Whitty for her thoughtful elaboration of conservation efforts in foreign lands. As keyboard environmentalists, it’s easy to vilify foreigners cultural or economic decisions. But I liken that to a foreigner selecting a cultural decision westerners make (buying large fuel-chugging vehicles for example) and passing judgement on that. Sure, there might be some truth to the judgement, but the issue is much more complex than the news headline.

“Would it be crazy for donors to subscribe like “$1 per vaquita, annually” to go to programs benefiting the fishermen and people who live in the area?”

You should build an app for that! I would support it.

Tim, yes the Totoaba is critically endangered and the fishery for it is illegal, that’s why it is run by the cartels.

Dear Tim,

As Wyatt mentions, the totoaba fish is listed as Critically Endangered – it used to be fished for its meat, driving it toward extinction. In fact, this fishery was an earlier threat to the vaquita, before the fishery was shut down due to the overexploitation of the totoaba, Fisheries then shifted largely to shrimp and only later has this illegal fishery for totoaba swim bladders significantly expanded.

I also agree that we need to be careful passing judgments on people existing in different social, economic, and cultural contexts, and that change will likely come more effectively through clear and compassionate communication versus antagonistic conflict.

Thank you, Wyatt – I appreciate that! Yes, we did not delve too deeply into the totoaba trade side of things. With this cross-border trade, there needs to be cooperation among the US, China, and Mexico along various topics, including enforcement of cartels.

And, of course, the US has consumed seafood responsible for vaquita bycatch (first, totoaba meat, then shrimp), so you could say that US consumers and various purveyors of seafood also bear responsibility!

Thanks for the comment, EUB!

To your first question: Candidly, I do not know. I believe that the demand for this species’ swim bladder jumped up when another species (yellow croaker) that was exploited for its swim bladder decreased. Here’s a link with more info: https://qz.com/468358/how-chinas-fish-bladder-investment-craze-is-wiping-out-species-on-the-other-side-of-the-planet/

I love your idea for donations aimed at helping communities as well as vaquita! I think campaigns aimed along these lines could have been hugely helpful in the earlier stages of this conservation story. It would have been interesting to see if donors or funding sources could leverage their funding to encourage conservation groups, for example, to link with social support NGOs. At this point, it’s down to last-ditch, emergency efforts for the vaquita, but this model would be fantastic for other sites, and also good to think about for long-term conservation in the Upper Gulf (especially if any vaquita are successfully captured and if there is any hope of someday reintroducing them into the gulf)

Ah! Another point: the current status of the totoaba is unknown, though the official status is Critically Endangered. A population assessment is a research priority for the area, and many of our interviewees expressed strong interest in this.

There currently are small-scale aquaculture operations, mainly at a university in Ensenada (UABC), where Dr. Conal True has developed great plans for expanding aquaculture operations to the communities of the Upper Gulf. Due to certain laws related to the breeding of endangered species, a certain percentage of these captive-bred totoaba must be released into the wild, which is tricky because at this point it is essentially resupplying an illegal fishery.

Is there any line caught fisheries operating there? If not any moves to set one up (or expand) and market it specifically as “sustainable fishery” helping to save the vaquita. The resulting higher prices could be offset/overcome by marketing directly to the millions of people interested in the issue. Id go out of my way to buy fish from a fishery like that (especially if Id just read the above excellent piece).

Great comment – there is definitely interest in “blue market” approaches to develop vaquita-safe products. And it’s great to hear that you would be a willing consumer!

At this point, it’s a bit too late for these approaches to save vaquita this time around – that is, these approaches take time. if the efforts to save vaquita via captivity, and someday reintroduce them, are successful, then it would be fantastic to have this project developed. I’d love to see something like this not only for vaquita, but for sustainable fisheries in general in the Upper Gulf – this could support improved livelihoods as well as improved fisheries management, and could also be a source of money to support the costs of keeping vaquita in captivity.

On that note, check out Aquarium of the Pacific’s “storied seafood” page, where they also have a great set of resources about the vaquita:

http://www.aquariumofpacific.org/seafoodfuture/storiedseafood