In the fossil history of sharks, a unique evolutionary experiment

happened much earlier than anyone thought.

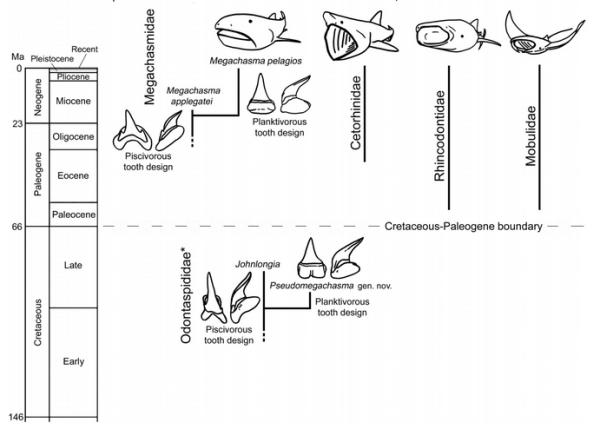

The largest fishes in the oceans feed on some of the sea’s smallest organisms. Several massive plankton-feeding elasmobranchs – the group of fishes that include sharks and rays – evolved adaptations to gulp huge mouthfuls of water and filter out plankton, shrimp, and small fishes. Though these tiny tidbits in themselves may not seem like a meal fit for a giant, the sheer abundance of these minuscule organisms in the sea adds up to a bounty for animals designed for sifting and straining them out of the water. What’s even more interesting is that each of the four massive filter-feeders evolved their particular diet and feeding morphology independently of one another.

Whale Sharks share a common ancestor with the docile nurse sharks, basking sharks are part of the branch of the shark family tree that has great white and mako sharks, the megamouth shark may be descended from the Odontaspidids, which includes the sandtiger sharks, and the manta rays are related to the much smaller bat rays and eagle rays. This is called convergent evolution, where natural selection steers the similar re-engineering of preexisting anatomical traits to achieve a similar solution between different groups of unrelated organisms. In the evolution of elasmobranchs over the last 45 million years, three lineages of sharks and one lineage of rays all independently evolved to filter-feed feed on plankton, swarms of tiny shrimp, and schools of small fishes as a means to successfully increase their survival.

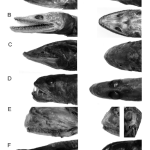

Farther back in time, during the Cretaceous period when dinosaurs roamed the land and huge marine reptiles swam the warm, shallow continental seas around the globe, this same experiment in filter-feeding evolved much earlier, and completely independently of any of today’s huge plankton-eating sharks. In a recent paper in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Kenshu Shimada and an international team of researchers unraveled the complex and confusing identity of several species of fossil shark teeth and found them to be the earliest known example of filter feeding in sharks. Small teeth from ancient marine rocks in Colorado, Texas, and Russia showed certain characteristics seen in recent giant filter-feeding sharks. In fact, the teeth looked so much like the huge deep sea filter-feeding Megamouth shark Megachasma, that the new genus was dubbed Pseudomegachasma.

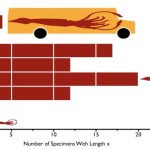

All of today’s filter-feeding sharks use highly-modified gills to strain food out of water that flows from their cavernous mouth through their gill openings. Not once do they appear use their teeth for feeding, so in these lineages of sharks, the teeth have become exceedingly reduced in size, usually barely a quarter inch in size. Unlike other instances in evolution where useless organs or appendages are eventually lost, in filter-feeding sharks the teeth didn’t go away, but they shrunk,

and strangely, increased in numbers rather than disappeared altogether, so filter-feeding sharks and rays have hundreds of itty-bitty seemingly useless teeth in their jaws. Fortunately, all sharks and rays shed their old teeth to make room for the new ones growing in, which is how such teeth from ancient sharks later become today’s fossils that guide our understanding of shark evolution.

These teeth from at least two different species make Pseudomegachasma the oldest plankton-feeding sharks yet known, and is believed to have evolved from an earlier, extinct fish-eating shark. Pseudomegachasma lived between 92-99 million years ago, first appearing in coastal waters that is now southwestern Russia, and later extending into the ancient inter-continental marine seaway that once covered an area from Texas to Colorado. Why Pseudomegachasma went extinct, and why there seem to be no giant plankton-feeding sharks between 50 and 91 million years ago is still a mystery that only future fossil discoveries can solve.

The research team consisted of Kenshu Shimada, DePaul University; Evgeny V. Popov, Saratov State University, Russia; Mikael Siversson, Western Australia Museum, Bruce J. Welton, New Mexico Museum of Natural History, and Douglas J. Long, California Academy of Sciences and St. Mary’s College of California.

Share the post "Before Giant Plankton-Feeding Sharks, there were Giant Plankton-Feeding Sharks."