In midsummer 2009, under the intense Mexican sun, a whale shark, MXA-182, arrived at Holbox. He is injured. A nasty cut nearly severs his right pectoral fin. His fin eventually heals, but a hole completely through his fin still persists. The hole’s shape earns MXA-182 the nickname of Keyhole.

In midsummer 2009, under the intense Mexican sun, a whale shark, MXA-182, arrived at Holbox. He is injured. A nasty cut nearly severs his right pectoral fin. His fin eventually heals, but a hole completely through his fin still persists. The hole’s shape earns MXA-182 the nickname of Keyhole.

In 2009, Keyhole is at Holbox to feed. His considerable stature requires a dense food source, such as ghost shrimp and copepods found at Holbox. A year later and every since, Keyhole switched to feeding at Afeura on masses of fish eggs.

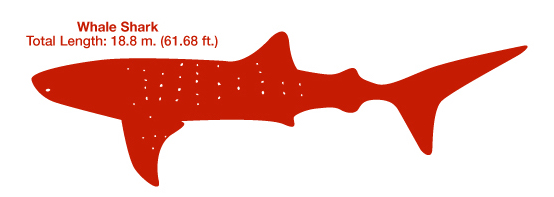

I encountered Keyhole two days ago in my first swim with whale sharks in the wild. I arrive at the Afeura excited and cannot get my mask, fins, and snorkel on fast enough. I toss my self over the port side of the boat. Two strong kicks later and I match Keyhole’s speed but only briefly. For once, and with mixed emotions, I am not the largest vertebrate in the ocean. By eye, I can judge that Keyhole is over three times my own length. The height of his tail fin is taller than myself at six feet. But precisely how large is Keyhole?

Why is knowing Keyhole’s length essential to understanding whale sharks? Repeated size measurements of Keyhole, can inform us of his health and feeding opportunities over his life. Whale sharks, like other sharks can actually ungrow. If a whale shark has a bad year, so to speak, the shark can reabsorb some of its cartilaginous skeleton for energy. A 24 foot long whale shark one year may be only 22 feet long the next year. If we have not only Keyhole’s measurements but all of his whale shark friends at the Alfeura, we can also know the age structure of the population. Is it mainly young and shorter sharks? Is the Afeura fun for all ages?

Measuring a formidable ocean beast on the move is at best a challenge and borders on impossible. No matter how many times I ask the whale sharks will not hold still long enough for me to use a tape measure. If I swim at my fastest I have a matter of seconds to minutes along side Keyhole or his colleagues, enough time for one or two photographs. However, I have a secret James Bond style weapon. Lasers.

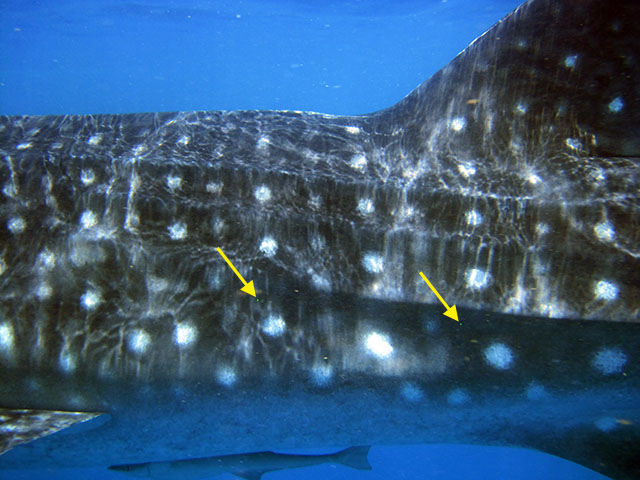

Two bright green lasers 50 centimeters apart, my camera mounted between them, shine on the side of whale shark. I quickly snap a photo. Knowing the distance between the two green dots on the shark’s flank, allows me to calculate the distance between any other two points in the same photograph, in this case the distance between the fifth gill and the start of the dorsal fin. To be close enough for the green laser dots to show up on the whale shark, doesn’t allow me to photograph the entire animal. But knowing the length from gill to fin and having a simple formula,allows me to extrapolate the length of the entire animal.

Sharks and lasers, never a more perfect union.