Our guest post is by Dr. Marah Hardt, a marine scientist and storyteller working to build a sustainable future for people and the sea. She is the Research Co-Director at Future of Fish and currently working on her first book, Sex in the Sea (www.sexinthesea.org). You can follow here on Twitter @Marahh2o.

Fifteen years ago we didn’t know they existed. In 2002 a handful of deep-sea invert experts playing with some underwater robots discovered the females gorging on bones of dead whales at the bottom of the sea. It was several months later before they found the males*— tiny, glorified sacs of sperm, one hundred thousand times smaller than the female, living in enormous harems inside her tube. Dozens of species have since been described, all showing giant females with a fetish for microscopic males…until now.

A new study by Rouse et al., (star detectives of the continued Osedax chronicles) adds another twist to the mind-blowing bizarreness and total radness of bone-devouring zombie worms. In this latest episode, hordes of enslaved dwarf males everywhere may gain a ray of hope: we now know there is at least one species of Osedax who has escaped the clutches of tiny-tude—rejoice, for the independent male Osedax has been found!

Meet Osedax priapus, from the Latin “os” for bone, and “edax” for devour, the species name “priapus” stems from the Greek god of procreation and “personification of the phallus.” Oh yes. These males are not only independent, they likely use their manly trunks as a penis to directly transfer sperm to the females. Say hello to the bone-devouring-I-am-my-penis worm.

Proposed motto: why have a penis, when you can be a penis?

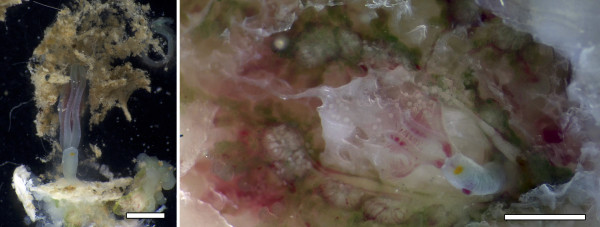

To recap for those of you not up to speed on the overarching awesomeness of Osedax, theirs is a life straight out of a B-grade alien flick. These annelid tube worms lack mouth or gut, so they can’t eat. Instead, taking a play out of the plant book, adults grow root-like structures with bulbous ends that protrude into decaying bones of dead animals on the seafloor. The roots dissolve the hard parts of the bone and then the remaining protein or fat is passed through the skin to symbiotic bacteria inside the roots. The worms then use the bacteria for food. Bonus bizarreness: these “roots” grow out from around the ovisac—it’s like a fibrous network of fallopian tube food-factories.

This ain’t your garden variety earthworm.

In addition to that, the females were known for this strange sexual obsession with stunted males. The current theory is that the first larvae worms to arrive to a whale fall develop as females; later worms settling onto female-covered bones transform into males, likely responding to a cue put out by the females. It’s a kind of environmentally controlled sex determination (ESD).

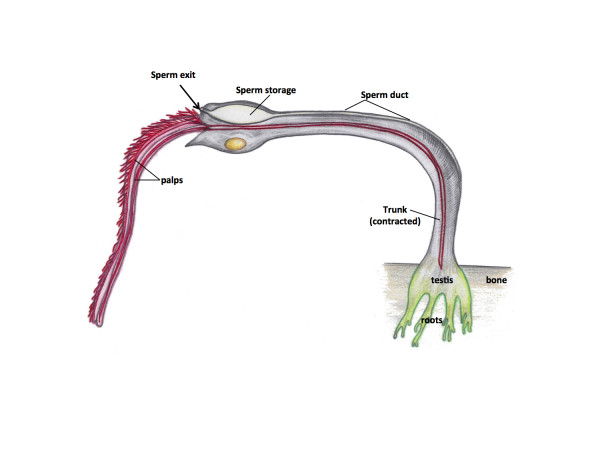

But these males aren’t just mini-me’s of the female. The trigger to become male halts the development of all adult features, except for the testes—those bad boys are fully grown, pumping sperm through a long gonadal duct from the back to the front end of the body, where it’s released through a pore just above the brain. Osedax males are basically larvae with gigantic testes that ejaculate out of the their heads.

Except for Osedax priapus. This species has large, free-living males, approaching the size of the females and capable of attaching to bones with that crazy root-structure. What’s especially impressive about this find is it shows evolutionary reversal of extremely complex characters. When your ancestors are all dwarf paedomorphs, it’s not easy to be a root-bearing giant phallus living the free life.

Yet, after running multiple phylogenetic analyses, Rouse et al. conclude that the most likely ancestry of O. priapus, is a species with extreme sexual dimorphism, aka, dwarf males. With its size, symbionts, and trunk structure, O. priapus represents one of the first times a reversal from paedomorphism has been documented in an animal (and it raises the question of the potential role of genetics in sex determination).

Although O. priapus has made giant strides away from a parasitic life, it is not completely free of its past. Like dwarf males of other Osedax species, O. priapus males still have free swimming sperm that shoot out from the top of their head. Free swimming sperm work well if you are a dwarf male living inside the female. Your sperm swim down the oviduct right to the eggs in the ovary. But free sperm don’t swim so well in seawater. Rouse et al. speculate that O. priapus males overcome this challenge through the use of their remarkably flexible trunk, reaching in to fertilize nearby females, much like the impressively extendable penis of some barnacles. Prehensile penises are a marvel.

Why and how O. priapus changed course from dwarf to free-living male remains a mystery. One hypothesis is that dwarfism benefits species with extremely limited resources: larger females would be able to produce more eggs, but they would monopolize the resource, making a dwarf male lifestyle advantageous. In O. priapus, the females are some of the smallest of any Osedax species, which means that there might be more room for males to squeeze in on the bone-devouring. Rouse et al. also note that O. priapus females make the smallest eggs of the genus. Since dwarf males rely on egg yolk as the energy reserve for fueling sperm production, tiny egg yolks might mean too few sperm for males to be successful as dwarfs. Feeding on the bones like a female could have allowed for greater sperm production.

From two deep sea species named in 2004 to almost two dozen today found in nearly every ocean, from the depths to the shallows, Osedax are proving to be rather cosmopolitan members of the ocean community. No doubt these sexual extremist scavengers will continue to break the bounds as more of them are described. Stay tuned.

Share the post "All Female Bone-Devouring Worms Fancy Dwarf Males, Except One"