Ocean conservation work takes me to many an unusual locale, but none stranger than tomorrow’s destination: Las Vegas. I’m headed there to attend the annual Diving Equipment & Marketing Association, or DEMA Show for short. The DEMA Show is the world’s largest international trade show for the scuba diving and water sports industry. The exhibition hall generally covers an area equivalent to a couple of US football fields and is the main draw of the event. Here diving equipment manufacturers get to showcase their latest, sexiest gear while dive shops, dive resorts, and tourism bureaus hope to advertize their offerings and attract dive tourism bookings. Walking the floor of DEMA you are surrounded by diving true believers. These people don’t like to dive… They LOVE to dive. And smoke. And then there’s the copious volumes of alcohol consumed. And the showgirls. In fact, if the National Rifle Association Annual Meeting and the Benny Hinn Ministries got drunk one night and produced a love child, it would be the Las Vegas DEMA Show.

Ocean conservation work takes me to many an unusual locale, but none stranger than tomorrow’s destination: Las Vegas. I’m headed there to attend the annual Diving Equipment & Marketing Association, or DEMA Show for short. The DEMA Show is the world’s largest international trade show for the scuba diving and water sports industry. The exhibition hall generally covers an area equivalent to a couple of US football fields and is the main draw of the event. Here diving equipment manufacturers get to showcase their latest, sexiest gear while dive shops, dive resorts, and tourism bureaus hope to advertize their offerings and attract dive tourism bookings. Walking the floor of DEMA you are surrounded by diving true believers. These people don’t like to dive… They LOVE to dive. And smoke. And then there’s the copious volumes of alcohol consumed. And the showgirls. In fact, if the National Rifle Association Annual Meeting and the Benny Hinn Ministries got drunk one night and produced a love child, it would be the Las Vegas DEMA Show.

But I digress. I love attending DEMA because it brings together many of the key stakeholders I have targeted in my ocean conservation work over the past several decades. My work has operated at the interface between coral reef and shark conservation and the marine tourism world. I believe that dive tourism professionals (like dive shop owners, dive instructors, dive guides, and naturalists) are an ideal target audience for conservation because they are in the water every day and can witness first hand any changes or disturbances on the ecosystem, often well in advance of scientific documentation. Also, since their continued profitability depends on the sustainability and longevity of the ecosystem, they have a vested (self) interest to be involved as active stewards in conservation. Or at least that’s my operating assumption.

I’ll be returning to the DEMA Show floor to continue discussions I began last year with international dive operators who market shark dive tourism as a primary focus or specialty.

The shark dive tourism niche is big business within the diving community and there’s no sign of this trend slowing down. Whether it’s fear or fascination, sharks consistently occupy the top-three most wished-for sightings on dive trips. I was recently in the Turks and Caicos Islands where a dive operator went so far as to say that for his business a dive trip was a success or a bust depending of whether guests could see a shark. The world’s biggest dive certification provider, PADI, now offers specialty courses in shark conservation and whale shark diving. Many dive shops are offering specialty courses in “shark awareness.” And diving industry media is paying close attention to all this interest with regular “top shark dive” features, as well as a dedicated issue to shark diving in Scuba Diving magazine.

The shark dive tourism niche is big business within the diving community and there’s no sign of this trend slowing down. Whether it’s fear or fascination, sharks consistently occupy the top-three most wished-for sightings on dive trips. I was recently in the Turks and Caicos Islands where a dive operator went so far as to say that for his business a dive trip was a success or a bust depending of whether guests could see a shark. The world’s biggest dive certification provider, PADI, now offers specialty courses in shark conservation and whale shark diving. Many dive shops are offering specialty courses in “shark awareness.” And diving industry media is paying close attention to all this interest with regular “top shark dive” features, as well as a dedicated issue to shark diving in Scuba Diving magazine.

The conservation community has also been paying close attention to this growing interest in shark diving as it represents a lever for building stronger protections for sharks. If a shark can be worth more alive as a tourism draw over the course of its life versus the one-time utilization value of that same shark for its meat and fins, it represents a potentially compelling argument to tourism bureaus and decision makers for establishing strong protection. Precisely this sort of analysis was done in the Micronesian nation of Palau which quantified the economic benefits of Palau’s shark-diving industry and found that its worth far exceeds that of shark fishing. In Palau’s case, the estimated annual value to the tourism industry of an individual reef shark was US$179,000 (or US$1.9 million over its lifetime). In contrast, a single reef shark would only bring an estimated US$108 for fins and meat. For Palau, it made good economic sense to establish permanent protection for sharks in their waters.

The conservation community has also been paying close attention to this growing interest in shark diving as it represents a lever for building stronger protections for sharks. If a shark can be worth more alive as a tourism draw over the course of its life versus the one-time utilization value of that same shark for its meat and fins, it represents a potentially compelling argument to tourism bureaus and decision makers for establishing strong protection. Precisely this sort of analysis was done in the Micronesian nation of Palau which quantified the economic benefits of Palau’s shark-diving industry and found that its worth far exceeds that of shark fishing. In Palau’s case, the estimated annual value to the tourism industry of an individual reef shark was US$179,000 (or US$1.9 million over its lifetime). In contrast, a single reef shark would only bring an estimated US$108 for fins and meat. For Palau, it made good economic sense to establish permanent protection for sharks in their waters.

Given the global threat to shark populations, I think anything that can create an incentive to keeps shark alive is a good idea. But one aspect that I’ve found more than a little curious about the emergent shark dive tourism sector is the apparent “free-pass’ the dive industry and scientific community appear to be giving around the feeding of sharks on some shark dives. Look, I’m a realist. I recognize that if you want to sell a “shark dive” (and be successful at it) you need to provide sharks on a regular basis. Contrary to the 70’s Jaws hype or any impression you may get from Shark Week dreck or Sharknado, sharks for the most part aren’t particularly interested in people. Especially groups of people during a dive, with their associated noise of bubbly-breathing. Often the sharks I see on dives are at the periphery of my visibility. I somewhat suspect this is by their choice. So if you want to shorten that viewing distance, you need to attract them. And with sharks that means providing food.

Over the past few years of discussing shark feeding with colleagues and friends within the dive and conservation community, I’ve found that few issues appear to be as polarizing as that of feeding (or provisioning) of sharks for tourism. My sampling has found that most respondents are either dead-set against the practice or they are okay with feeding provided precautions are taken. Few

Over the past few years of discussing shark feeding with colleagues and friends within the dive and conservation community, I’ve found that few issues appear to be as polarizing as that of feeding (or provisioning) of sharks for tourism. My sampling has found that most respondents are either dead-set against the practice or they are okay with feeding provided precautions are taken. Few  individuals I’ve met appear to take a middle position on the subject or are neutral. My own initial hesitancy around the idea of feeding sharks was based more on the copious terrestrial case studies we have that demonstrate the feeding of wildlife generally doesn’t end well for the wildlife. Wildlife can become habituated to and dependent upon human-provided food, and overly persistent, curious, or aggressive animals can result in human injuries or death which then often necessitates wildlife being destroyed. (This isn’t even factoring the reality that many of the foods being fed to wildlife are ill-suited to their metabolic needs. I recently received this image (right) from a friend in Tahoe of what she calls a “Garbage Bear.”)

individuals I’ve met appear to take a middle position on the subject or are neutral. My own initial hesitancy around the idea of feeding sharks was based more on the copious terrestrial case studies we have that demonstrate the feeding of wildlife generally doesn’t end well for the wildlife. Wildlife can become habituated to and dependent upon human-provided food, and overly persistent, curious, or aggressive animals can result in human injuries or death which then often necessitates wildlife being destroyed. (This isn’t even factoring the reality that many of the foods being fed to wildlife are ill-suited to their metabolic needs. I recently received this image (right) from a friend in Tahoe of what she calls a “Garbage Bear.”)

Another somewhat troubling aspect of the uptick in shark diving interest that is related to but not necessarily coupled with the practice of shark feeding is the insistence that sharks “are our friends.” One of my more avuncular friends has labeled this the “dolphinization” of sharks. I’ve noticed that some individuals are in such a rush to convince others that sharks are benign and “tame” and thus worthy of protection that it’s led to a glut of imagery and antics that starts to take us into Timothy Treadwell territory (Treadwell was a self-styled grizzly bear conservationist whose insistence that Alaska grizzly’s could be safely observed at close range led to his death, the death of his fiance, and ultimately the death of two bears). More on the potential downside to wildlife from our uninformed interactions later.

Like any scientist, I turned to the literature to see what had been published on impacts from shark feeding. Not surprisingly, the literature on the subject is relatively thin. What data existed seemed to focus upon the behavioral impacts to sharks from provisioning. In two studies (one in Fiji on bull sharks, the other in the Bahamas on tiger sharks), investigators concluded that the practice of feeding showed temporary behavior changes during the act of feeding, but aggregated sharks mostly dispersed immediately following feeding. In the case of the Bahamian tiger sharks, fed sharks hung around less and showed broader movement patterns than Florida tiger sharks. It’s hard to draw conclusions on the impacts from feeding sharks from a few studies. And it’s important to consider factors such as the dive shops that were being observed. In both the Fiji and Bahamas cases, the dive operations are what I would consider at the top of their game, use rigorous safety protocols, and feedings are highly choreographed. What does fed shark behavior look like when such rigor or routine is not as carefully applied?

Like any scientist, I turned to the literature to see what had been published on impacts from shark feeding. Not surprisingly, the literature on the subject is relatively thin. What data existed seemed to focus upon the behavioral impacts to sharks from provisioning. In two studies (one in Fiji on bull sharks, the other in the Bahamas on tiger sharks), investigators concluded that the practice of feeding showed temporary behavior changes during the act of feeding, but aggregated sharks mostly dispersed immediately following feeding. In the case of the Bahamian tiger sharks, fed sharks hung around less and showed broader movement patterns than Florida tiger sharks. It’s hard to draw conclusions on the impacts from feeding sharks from a few studies. And it’s important to consider factors such as the dive shops that were being observed. In both the Fiji and Bahamas cases, the dive operations are what I would consider at the top of their game, use rigorous safety protocols, and feedings are highly choreographed. What does fed shark behavior look like when such rigor or routine is not as carefully applied?

My mission to see sharks protected and my rationale that shark dive tourism can be a powerful lever for that protection led me down a path of interest in seeing shark diving being successful and as safe and sustainable as possible. This interest drew me more closely into the shark diving world than I had previously been familiar. I’ve been immensely fortunate that my work takes me around the world, and I’ve capitalized on opportunities to see first-hand what shark diving looks like under numerous scenarios. With no exaggeration, I’ve been on spectacular shark dives and uneventful shark dives. I’ve felt remarkably safe and well-looked after and I’ve felt abandoned and scared shitless. I’ve seen sharks relaxed and orderly during feedings and I’ve seen full-on frenzies. My very personal and subjective (although I also suspect accurate) summary on what I’ve observed to date is that there is money to be made on shark dive tourism and it is a powerful incentive to “get in on the action,” regardless of experience and awareness of lessons learned. And like all businesses, there’s a continuum of what I would consider sustainable practice… some are deeply invested in good training, supervision, and safety and some are in it to simply turn quick profit.

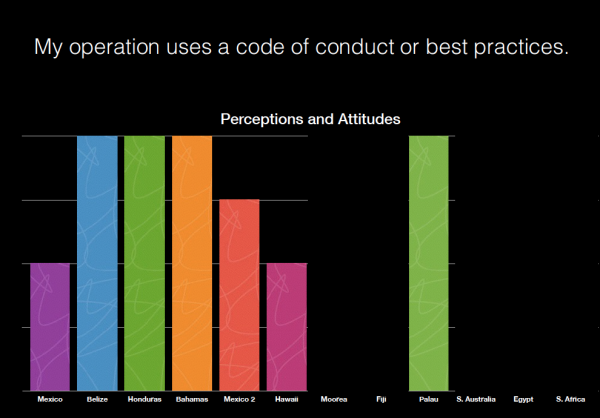

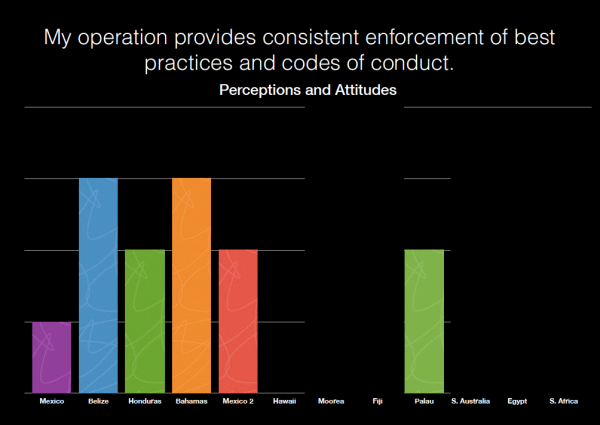

In hopes of trying to help inform how a focus on best practices, lessons learned, and potentially a code of conduct could assist the shark diving industry, I embarked on what is (to my my knowledge) the first systematic global assessment of current practice within the industry. I wanted to capture a snapshot of shark diving that is diverse geographically as well as with respect to species of sharks observed. As you might expect, not an easy task. Not many operators are keen to share their operational sausage-making with strangers. But it pays to build bridges and relationships over a conservation career, and I’ve been slowly assembling a picture of the state of shark diving that I believe can be instructive. On the eve of heading to DEMA to continue discussions, I thought I’d share some of my findings. Using a two-page interview that asked respondents to answer questions along a range from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” I’m already getting some interesting returns. On the tables below, “strongly agree” is at the top of the y-axis, “strongly disagree” is at the bottom of the y-axis:

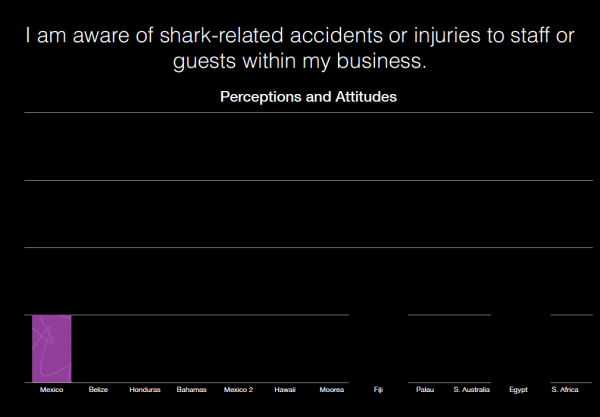

I also turned this question around to ask whether respondents were aware of shark-related accidents or injuries to staff or guests within their competitors businesses. This is one of those times when you can actually catch yourself laughing during data crunching:

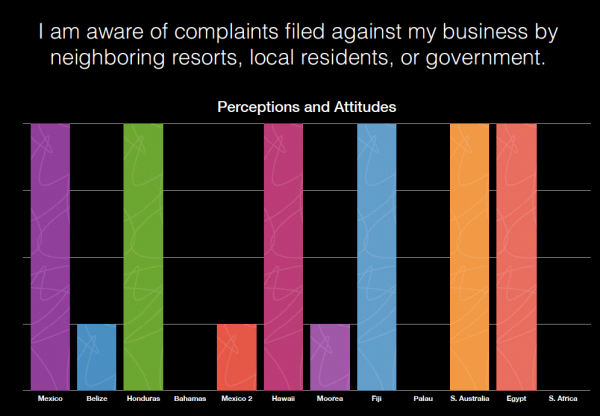

One question asked respondents whether they were familiar with complaints filed against their business by neighboring resorts, local residents, or government:

I find this question to be one of the more interesting for the survey. The protection and safeguarding of sharks that you aggregate through feeding is an important foundation for a shark dive business. After all, a reliable supply of sharks for viewing is key to the shark dive tourism model. It’s one thing to be fond of aggregating sharks as a shark dive business. But what do your neighbors, particularly in destinations with sand and sun tourism, think about aggregating big predators in proximity to beach goers? And if you want to keep complaints to a minimum and safeguard your business from intrusion by neighbors or government, doesn’t it stand to reason that you would take precautions that demonstrate you are minimizing risk to your clients or your neighbors clients? I believe there’s an important policy implication in this aspect of shark diving that should not be undersold. And we have some precedent of what can happen when we ignore this connection.

The inset picture on the left is of a bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) that was taken on a beach dive I did several years ago just south of Cancun in Mexico’s Riviera Maya. The dive operator approached us on the beach and offered to take us to see bull sharks that naturally aggregate each winter in that part of Mexico. We entered from the beach, swam out perhaps 50 meters from shore, sank with extra weights to the bottom, and waited for the guide to join us with a bucket of dead fish that he dumped on the sand in front of us to attract the bulls. I saw perhaps three bull sharks on the dive. None fed on any fish, but I was fine with that since by the time the bulls showed up the fish was drifting very close to our legs and the slick of fish oil was everywhere around us. All in all it was a creepy dive with poor visibility, skittish sharks, and seemed like an accident waiting to happen. And I was consistently conscious of how too close to shore we seemed to be for this feeding to be happening.

The inset picture on the left is of a bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) that was taken on a beach dive I did several years ago just south of Cancun in Mexico’s Riviera Maya. The dive operator approached us on the beach and offered to take us to see bull sharks that naturally aggregate each winter in that part of Mexico. We entered from the beach, swam out perhaps 50 meters from shore, sank with extra weights to the bottom, and waited for the guide to join us with a bucket of dead fish that he dumped on the sand in front of us to attract the bulls. I saw perhaps three bull sharks on the dive. None fed on any fish, but I was fine with that since by the time the bulls showed up the fish was drifting very close to our legs and the slick of fish oil was everywhere around us. All in all it was a creepy dive with poor visibility, skittish sharks, and seemed like an accident waiting to happen. And I was consistently conscious of how too close to shore we seemed to be for this feeding to be happening.

In the years since this dive, shark dive tourism exploded in Mexico’s Yucatan. One excellent operation in Playa del Carmen that legitimately pioneered bull shark diving in the Yucatan grew into several copy cat businesses, including some very fly-by-night operations. Shark diving and feeding began to be offered in locations uncomfortably close to shore along Playa del Carmen’s heavily populated resort beaches. The Hotel Association of the Riviera Maya began to receive complaints from hotel owners and other concerned businesses. With this as a backdrop, in January of 2011, a tourist had a serious chunk of her thigh and upper arm removed by a bull shark in Cancun. Fingers were pointed in many directions at the time, and many local voices raised concerns about the shark feeding so close to shore. The local government responded by issuing a cull order to fishermen from Cancun to Playa del Carmen. Many sharks, mostly pregnant females, were caught and killed as a demonstration of action by the municipality.

In the years since this dive, shark dive tourism exploded in Mexico’s Yucatan. One excellent operation in Playa del Carmen that legitimately pioneered bull shark diving in the Yucatan grew into several copy cat businesses, including some very fly-by-night operations. Shark diving and feeding began to be offered in locations uncomfortably close to shore along Playa del Carmen’s heavily populated resort beaches. The Hotel Association of the Riviera Maya began to receive complaints from hotel owners and other concerned businesses. With this as a backdrop, in January of 2011, a tourist had a serious chunk of her thigh and upper arm removed by a bull shark in Cancun. Fingers were pointed in many directions at the time, and many local voices raised concerns about the shark feeding so close to shore. The local government responded by issuing a cull order to fishermen from Cancun to Playa del Carmen. Many sharks, mostly pregnant females, were caught and killed as a demonstration of action by the municipality.

I’m not saying that Mexican shark dive tourism caused the tourist injury. I can’t make that casual connection. But I can say that the lack of a rigorous code of conduct, the lack of meaningful safety protocols to dive clients, and the lack of serious consideration of community concerns made it easier for the local government to act in the manner they chose. The end result is that whatever gains we may have made in perceptions and attitudes about sharks and the need for their protection got undermined by this unfortunate incident. And there are other similar stories that I’ve heard around the world.

That was then. This is now, and I’m now off to Vegas to continue discussions with shark dive tourism operators who are eager to see some leadership step forward with regard to developing best practices within their industry. Some of this is happening from within, and you will likely be hearing more about Global Shark Diving as an industry-led initiative. And there are efforts underway through collaborations between NGOs like WWF, The Manta Trust, PADI Project Aware, and academia to try to formalize best practice and perhaps certification. And I’m working to build-out Sustainable Shark Diving as an open source collection of existing lessons learned as well as customer reviews a la Trip Advisor. Certainly a lot of new tools are on the horizon, and I’m excited to keep things rolling this week at the DEMA Show.

For once, I’m hoping that what happens in Vegas doesn’t stay in Vegas.

I wonder how many of those eager to start businesses poised to “bring predators closer to tourists by feeding them” would be willing to swim adjacent to an alligator park that operates an open access (to the alligators) facility(?)

Feeding predators and associating “us with free food” is as bad for us, as it is for the sharks in question. On the human side, those who are squeamish of such approaches, and are armed and who are willing to “stand their ground” (in the animals habitat) means the animal is more likely to be killed approaching those not involved with the feeding exercises..

Repeat feeding wild animals (including predators) sets them up by taking away their normal behavior (hunting) making them instead dependent (on sums level) with the food supplied. It might also create “artificially large” feeding aggregations (that did not exist due to the repeated nature and reliability of food supply) bringing more to feed. This might cause the possibility of pathogen transfers between the sharks (squabbling for food) etc.

nice article im loving it