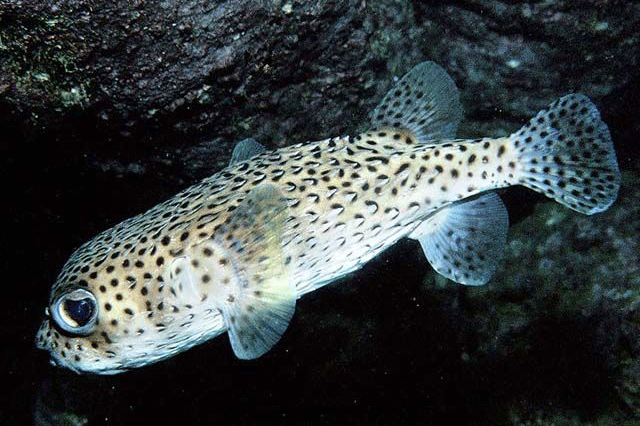

As scientific mariners, we spend an inordinate amount of shore time on sleezy docks and seedy piers around the world, from the gritty shipyards of Callao, to the bustling ports of Capetown, and the rowdy embarcaderos of Barbados. These landings provide a chance to shake off the sea legs on tierra firma, and sample the local hooch at a shady watering hole with friendly natives. But down a dark alley I might get cornered by a group of local street thugs, demanding my valuables at the business end of a blackjack, further armed with a menacing snaggle-toothed sneer. But then BAM! – I instantaneously double my size, bearing hundreds of switchblades in an impenetrable orb of pain and awe. “How do you like me now, punks!”. And off the crooks scram with a hasty retreat, while I regain my demeanor and make it safely back to the ship. Yeah, it would be awesome to be a Spotted Porcupine fish (Diodon hystrix).

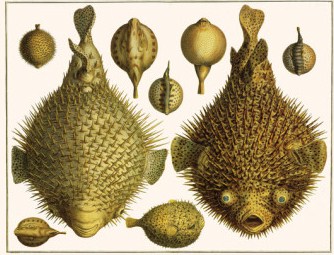

The name “Blowfish” is a clumsy non-scientific term that includes two very different groups of related fishes. The true pufferfishes, the Tetraodonts, have upper and lower beak-like tooth plates in pairs, but the Diodonts have a single upper and lower tooth plate. This second group contains the porcupine fishes and the slightly less spiny burrfishes. Both groups don’t really ‘blow’, but have the ability to quickly take up water or air through their mouth into a cavity between their body and their elastic skin to inflate like a balloon, increasing their size to scare off potential predators, or making themselves too large to even swallow.

Porcupine fish up their game by erecting dozens of rows of long, sharp spines, originally derived from scales, making themselves even more of an unpalatable and impossible mouthful. Once reconsidered, passed-over, or spat out by a predator, they deflate, the spines lay flat, and off they go. Well, usually. Tiger sharks are the honey badgers of the reef, and don’t give a care about the Spotted Porcupinefish and will readily eat one spines and all. Itty-bitty porcupinefishes, too small to pose a bother to big gamefish, are often swallowed whole by much larger tuna, jacks, mahi mahi, and grouper. The ichthyological literature documents instances where a porcupine fish inflated half-way down the gullet of a fish, blocking the gill chamber and causing the larger fish to choke and asphyxiate, and at the same time, killing the porcupine fish too. But evolution works by beneficial adaptations being successful most of the time, not necessarily all of the time, and their self-defense strategy mostly works most of the time.

Tough, beak-like tooth plates powered by strong jaw muscles in their big head allow porcupine to munch and crunch crabs, barnacles, snails, clams and other hard-shelled invertebrates. These tooth plates are often found as fossils, dating back to the Miocene period some 25 million years ago, attesting to the fact that morphing into a big ball of spikes is a time-tested way to stay alive on the tropical and warm-temperate coasts around the world where they still live today.

Persistent mythology holds that this sharp, powerful beak can be used by living, swallowed porcupine fish milling in the belly of a beast to literally chew their way out of the stomach, muscle, and skin of a large predator, a myth promulgated by none other than one Charles Robert Darwin. In the Voyage of the Beagle, he recounts a vague second-hand account of a porcupine fish literally eating its way out of the body of a shark, with Darwin commenting “Who would ever have imagined that a little soft fish could have destroyed the great and savage shark?” Indeed not, because it likely never happened, and such an incident has never been documented in the centuries since Voyage of the Beagle was published. But just-so stories are certainly hard to kill, and seem to just eat their way right out of the belly of fact and reason, just like in this 1930 Ripley’s Believe It Or Not cartoon:

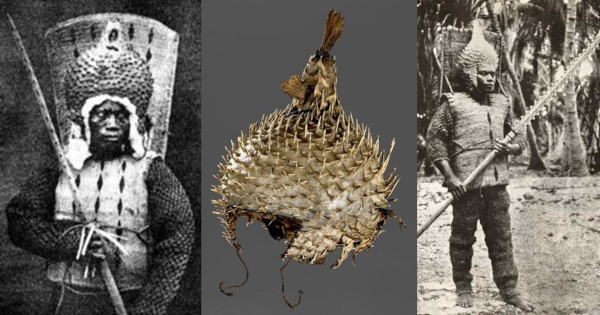

The defensive warning afforded by porcupine fish spines has been used for centuries by warriors of the Oceanic islands. Sporting a spotted porcupine fish skin dried and shaped into a helmet, men of Kiribati and Nauru wore them to intimidate opponents and make it difficult to land a blow to the head with the shark tooth-studded clubs they used to fight each other.

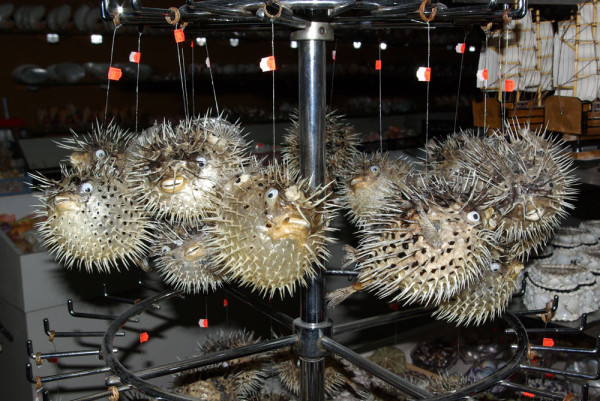

Because the inflatable outer skin is loosely connected to the inner body of the fish, allowing for the expansion of water in the space between skin & carcass, it’s quite easy to peel the entire skin off the fish, and that is the basis for numerous cottage industries throughout the tropics. In the Philippines, the porcupine fish are skinned with the tooth plates retained in the mouth, and the loose skin is then filled with sand, kapok, or even an inflated balloon, and left in the sun to dry, resulting in a hardened, spiny, ball-shaped body forever capturing that moment of surprise and self-defense. These are then sold into the worldwide sea-life curio trade by the hundreds of thousands. Every shell store in any beach-side shopping district around the world has them for sale. Google-eyes are optional.

Whether it was because Oceanic islanders incorporated porcupine fish into their culture, or that tropical flotsam and jetsam often contained shore-cast and sun-dried porcupinefish, these critters have become an iconic part of tiki culture.

Since the late 1930’s, global travelers and maritime vagabonds recreated the care-free atmosphere of the tropics in the manner of kitschy tiki bars which later ballooned into a country-wide phenomena as WWII soldiers and sailors returned from the Pacific theater and sought the exotic flavor of the islands. Among the tiki style’s mandatory rattan & bamboo, glass floats & fish nets are porcupine fish. Inflated, dessicated, and impregnated with a light, hanging as a mace-like lamp, they provide little real illumination yet highlight their impressive spiky armor. Finer tiki establishments, those that harken back to a boozy Giligan’s Island aesthetic, may also serve drinks in glazed ceramic mugs in the likeness of a porcupine fish.

So the time in St. Kitts, after stumbling out of a rum shack in the wee hours and encountering a man with a machete demanding my valuables, I could only dream of defending myself like a spotted porcupine fish. Alas, I could not, so I calmly handed over my sterling money clip, sandwiching the last few tattered Eastern Caribbean Dollars, without further incident.

Here’s a little sumthin’-sumthin’ for the DIY marine biology & interior design set:

Share the post "These Are a Few of My Favorite Species: Spotted Porcupine Fish"