“I know you drowned him in the ocean, these bones don’t lie…”

Ever heard of forensic limnology? Neither had I, until I had a random conversation during a coffee break.

The police find a body in the water. How did it get there? How did this person actually die? Was this a tragic accident, or perhaps something more malicious?

The fateful anecdote, the one that enticed me to write about this topic, goes something like this: A mob informant suddenly turns up dead. At first glance, the death doesn’t look suspicious – he was surely drunk when he fell off that balcony. But something’s not quite right. The bleeding appears to be postmortem, the autopsy shows water in the lungs. It’s well known that the local mob wanted this man dead. But how do prosecutors build a case?

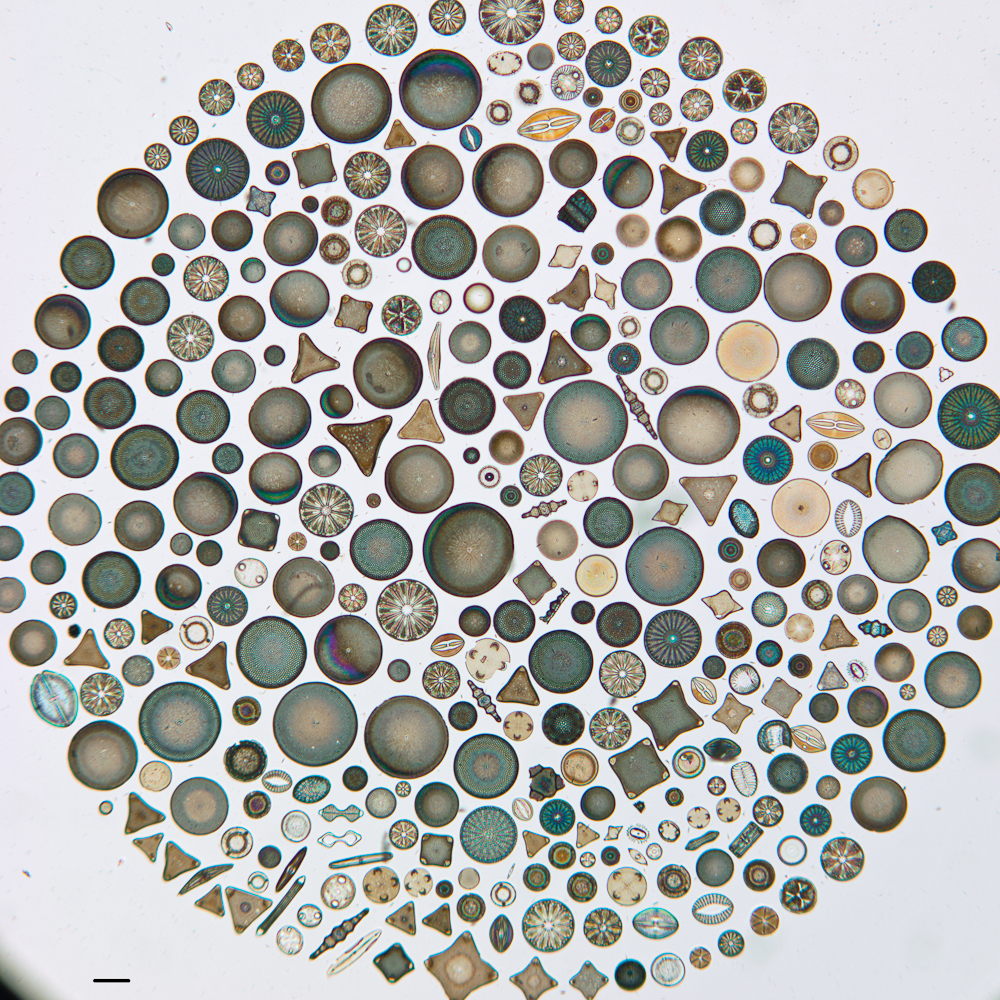

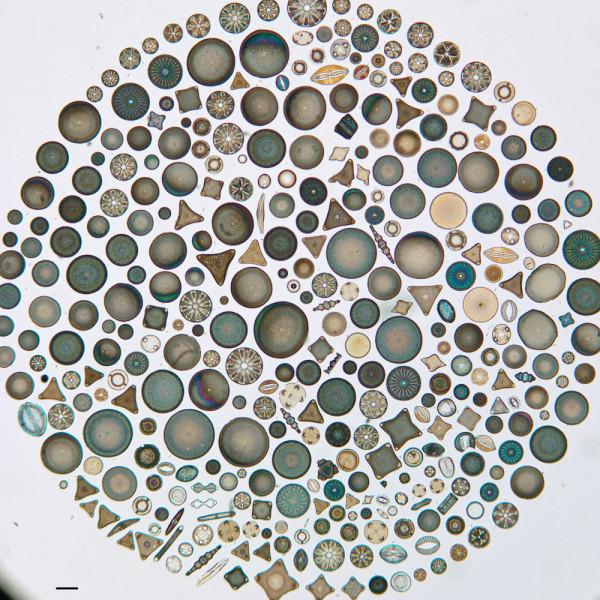

To solve this mystery, we have to rely on diatoms. I’m talking about tiny, single-celled species of algae with “shells” made of silica (sidenote: this shell is actually a cell wall called a frustule, which is by far the awesomest anatomical term in marine biology!!). Diatoms under the microscope look something like a kaleidoscope, and I probably wouldn’t try to study them if you’re on LSD:

Diatoms live EVERYWHERE where there is water: oceans, lakes, rivers (and even soil). They are used to monitor and assess water quality. Diatoms are also probably in your cat litter and toothpaste. In fact diatoms are damn useful for many many things, even for determining the age of rock and sediment layers – diatom cell walls are so well preserved in the fossil record and have been so extensively studied by scientists, that we know almost exactly when different species appear and disappear in geologic time.

Where else are diatoms well preserved? IN DECOMPOSING BODIES!!!!

Back to our case – diatoms provide key evidence for forensic investigations of suspected drowning deaths. As a person drowns, they inhale water into the lungs. This water, along with any microscopic animals floating around, gets taken up by the bloodstream and circulated around to the internal organs. Following drowning, Diatoms are known to aggregate in the bone marrow (especially the long bones such as the femur). These microscopic creatures are particularly critical in autopsies, because, well…

For the decomposed corpses and skeletonised body [sic] found in water…the diagnosis of drowning is rather difficult because those ‘‘drowning signs’’ were destroyed. Here [the] diatom test stands as the only direct screening test for drowning [1]. (Vinayak et al. 2013)

The collection of diatoms in a victim’s bone marrow represents a microbial “fingerprint” of the time and place where drowning occurred. Each lake, river, estuary and ocean contains a unique community of diatoms. The mix of species found in any given location also fluctuates over time, and varies according to season. So upon finding a body, a medical examiner can deduce whether a person drowned in freshwater or saltwater — or if death didn’t occur by drowning at all. On the other hand, if a person was forcibly drowned in a bath (and then maybe their body transported out to sea), their body tissues wouldn’t show any evidence of diatoms, since only filtered, diatom-free tap water would have been ingested at the time of death (before the heart stops beating). Diatoms have even been used to convict criminals in attempted drownings, where the species assemblages on the perps’ sneakers were shown to be pretty much identical to the species found in the “crime scene pond”.

In the case of our fallen mob informant, the courts would need to build up a solid body of evidence to prove that the accident was staged. A forensic investigator would perform an autopsy to remove bits of the brain, liver and bone marrow. “Femers are longitudinally sectioned using a clean band saw…” (Verma, 2013) – and then dissolved in acid. The gooey mix of liquified tissue is centrifuged and purified, and the slurry that remains is examined under the microscope to look for diatoms and identify the species present. The police can go even further and collect swabs of dirt from suspects’ shoes and homes. Since diatom communities can fluctuate quite a bit over space and time, guilt could be easy to prove if the “fingerprint” of diatom species shows an exact match between the suspect’s shoes and the victim’s bones. But one thing is certain – our man drowned. The biology don’t lie!

Case. CLOSED!

References:

Cox, E. J. (2012) Diatoms and Forensic Science, in Forensic Ecology Handbook: From Crime Scene to Court (eds N. Márquez-Grant and J. Roberts), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK. doi: 10.1002/9781118374016.ch9

Vinayak V, Mishra V, Goyal MK (2013) Diatom Fingerprinting to Ascertain Death in Drowning Cases. J Forensic Res 4: 207. doi:10.4172/2157-7145.1000207

Pollanen, M. S., C. Cheung, and D. A. Chiasson. “The diagnostic value of the diatom test for drowning, I. Utility: a retrospective analysis of 771 cases of drowning in Ontario, Canada.” Journal of forensic sciences 42.2 (1997): 281-285.

Verma, Kapil. “Role of diatoms in the world of forensic science.” J Forensic Res 4.181 (2013): 2.