For African Penguins, humans can make really lousy neighbors, but they have even bigger problems.

In real estate it’s all about location, location, location. A cozy home with an ocean view, white-sand beaches, comfortable climate, close to great food, and good neighbors. But that last part is currently giving penguins a problem. Boulders Beach, a suburb of Simon’s Town south of Capetown, South Africa, is a picturesque seaside community with 60,000 visitors a year and a resident population of 2,100 African Penguins struggling to live and breed among the vacation houses and beachgoers.

Penguins led a difficult and ultimately tragic parallel history with humanity in South Africa extending back nearly half a million years. Prehistoric foraging by early humans likely had little impact on the once expansive populations of these seabirds. As early as the 1600’s, penguins in South Africa – numbering perhaps in the tens of millions – were harvested on a large scale by European settlers, increasing through the 1800’s, they were boiled for their oil, and ground into hog feed. Eggs collected for human consumption at the breeding rookeries took the largest toll – over half a million eggs were taken in some years at one island alone, and the practice wasn’t banned until 1968. Mining of penguin guano for fertilizer (the ‘white gold’ of penguin droppings) not only disturbed the birds on their breeding sites, but crushed the burrows the birds needed to escape the South African heat and protect their eggs from gulls and ibises. Moreover, guano is a necessary link in coastal productivity, so less fertilizer that makes it back into the ocean means fewer nutrients for the base of the food chain, ultimately causing a decline in the fish the penguins need. Add to that the usual loss of habitat, impact from invasive predators, over-fishing of their preferred prey, and general human disregard for a very loud, very stinky bird.

Population estimates of African Penguins in the early 1900’s may have been as high as 3 million penguins, sinking to less than 300,000 during the first census in 1956, by the 1990’s penguin populations declined by more than 90%. Surprisingly in the mid 1980’s, a single pair colonized Boulders, with new breeding pairs arriving in following years, and later their offspring returning to breed, by the end of the last century, the Boulders Beach colony grew to nearly 4,000 animals, of those, 2,100 were breeding birds.

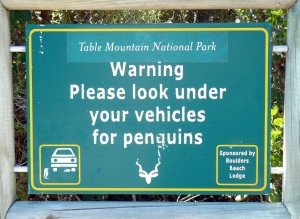

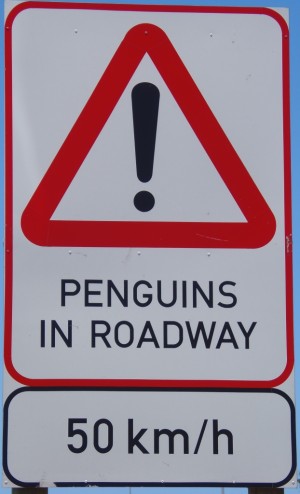

Part of Boulders Beach is a sandy-white strand of the Table Mountain National Park reserved just for the breeding birds, with a boardwalk for visitors to cross over the penguins for observation & appreciation. The remaining coastal strip is a jumble of rocks, small beaches, and coastal scrub. It’s this scrub where the penguins find shade from the heat and sometimes build their simple nest. Getting to that habitat after a day’s fishing along the coast means a mad scramble between beach blankets, forced photographic pairings with selfie-crazed tourists, and crossing several busy roads. Death by roadkill is only a recent risk in their evolutionary history, as are the poor penguins seeking a cool respite under a parked car, unknowingly crushed by the driver backing out of a parking spot. A variety of signs warning people of such dangers to the local penguins makes for an oddly comedic experience.

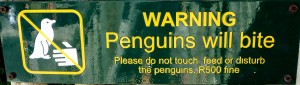

This new suburban environment is a strange place to survive. Where penguins once feared predation from brown hyenas and leopards, or egg loss from genets and mongoose, today they fear off-leash dogs, feral cats, and the hundreds of gulls lured to the beach by leftover food strewn on the shore that find an unguarded penguin egg too tasty to pass. Curious children chase the birds, hoping to cuddle these cute animals. But unlike the animated critters they know and love, cranky African Penguins pack a serious defensive bite, sort and twisted by a pair of sharpened pliers.

I was once bitten by an African Penguin named Elvis at the California Academy of Sciences, so I know the intense pain they inflict. These penguins are more ‘street’ than Happy Feet. Even though warning signs are posted, and a fine for touching a wild penguin is 500 Rand (about fifty U.S. bucks), penguins are harassed every day by a few idiotic tourists. But that’s just one downside of the neighborhood. In other areas of South Africa, large oil spills have made a huge dent in some populations, and even rescued oiled birds only have a 50% chance of survival after cleaning & rehabilitation. Locally, the less obvious but far more numerous small oil leaks from commercial and pleasure boats kill dozens more penguins each year.

While humanity can be an annoying and often fatal drag on the penguins, the bigger problem is the loss of their local marine cuisine. Their preferred prey are delicious, high-fat sardines, virtual Twinkies of-the-sea, that fatten both parents and chicks. Once the sardine fishery was over exploited a few decades back, leaner and smaller anchovies moved in to occupy their ecological niche. But their lower fat content made them less than ideal for raising a family, and penguins needed to spend more time catching more anchovies, causing an energetic drain on the birds. As a second-choice meal, anchovies still provided penguins with abundant food. In more recent years, the anchovies have also become a targeted commercial fishery, and data show a direct correlation between increase in commercial take of anchovies, and a reduction of nest success and adult survival of penguins. The bad news: African Penguins are on the decline again. Current estimates suggest that about 2% of the population from a century ago still survives.

Every so often I get the chance to teach a month-long university field course on wildlife biology & conservation in South Africa, and I take my students to Boulders Beach, mostly because it’s beyond awesome to snorkel with penguins, but it’s also a great way to engage students in the complexity of current-day conservation issues. Invariably one asks “why are all the penguins are here with the people?”, and I flip the question around: “why are people here with all these penguins”? It’s the monetization of the wildlife experience, and a unique one at that. The town knows the financial draw the penguins have, so it’s in their best interest to preserve them. Mo’ penguins, mo’ money. Working with the residents, local schools, and visitors, the National Park and non-profit groups are better educating visitors on penguin etiquette, providing more helpful signage, and creating the accommodations the penguins need. Currently, the local population of penguins at Boulders are still hanging on, but projected impacts from climate change, fisheries trends, increasing marine plastics, and coastal development don’t bode well for other populations throughout South Africa. The deeply-ingrained sense of conservation among South Africans, buoyed by the cooperation of government, researchers, non-profit organizations, and dedicated citizens, provide hope that African Penguins may not be totally lost.

attractive