Though we might not think much of the small pond Hydra, it’s got an incredible secret superpower. It spends much of its day extending its small tentacles and waiting for food to pass, but when the going gets rough for this little critter, it’s ready to respond. To discover its crazy trick, you need only to grind it to pieces.

To fully appreciate how bizarre Hydra is, put yourself in its shoes. Imagine you’re a Hydra, and you’re slowly being torn apart. Cell by tiny cell you are disassembled, and in the end nothing is left of you but a soup of your own bits, smeared on the bottom of a bowl. But you’re not dead, and you’re not going to be.

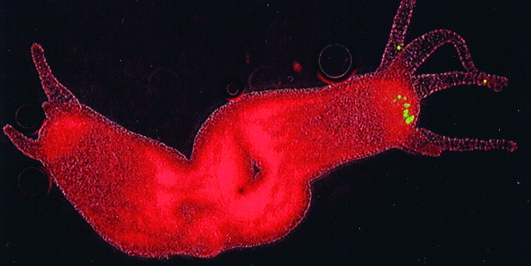

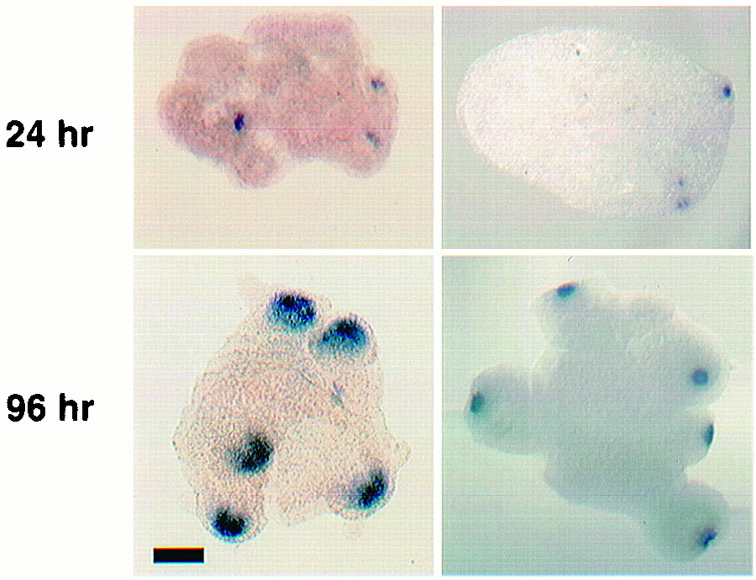

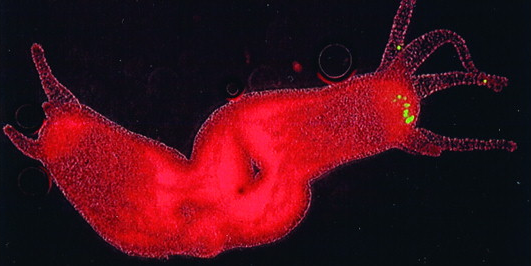

This is where things get interesting. Your cells begin to creep and crawl. They form small mounds as they come together and begin holding to each other. These mounds rise like mountains from your sea of cells, growing bigger as time passes. Slowly, recognizable forms begin to take shape. Mouths develop, and small tentacles stretch out into the water. Suddenly little bodies everywhere have regrown. Like Dr. Manhattan from The Watchmen, you’ve pulled yourself back together. And now you are not just one. You are many. But how did you do this?

How can an animal like Hydra pull off a stunt rarely seen outside Hollywood? This is what a scientist with a knack for grinding Hydra wanted to know. His name is Ulrich Technau, and along with a team of scientists he discovered something extraordinary about these little pond animals. The secret to surviving being blown apart is all about keeping your head.

At least if you’re a Hydra. Your head wasn’t much to look at when you were all put together, a mouth and some tentacles, but it turns out there was more to it than meets the eye. Your head was like a military command center for the rest of your body, constantly sending cellular orders telling your other body parts where to go and what to be. But that was before you were smashed apart. Now your head is totally disintegrated. But if even a few cells keep their identity as head cells, or start acting like they were part of the head (even if they weren’t) that’s all you need. These head cells will begin organizing the cells around them to form a new body.

If you’re a Hydra that’s been pulverized, all you need to come back together, according to Ulrich Technau and the team, is between 5-20 head cells from the command center of your former body. They will take charge, releasing their specialized molecules, like cellular orders, that command other cells to start taking shape. Once a cellular mound has formed around them, it’s just a matter of each member of the mound falling into place, and a new animal is formed.

Because there were many more than 20 cells in the original head, and because these cells will be spread haphazardly around the dish, they will command multiple mounds to form and make new bodies. Where there was one animal, now there are lots.

For the Hydra at least, this neat trick may mean fast recovery from predator attacks in the wild. If even a small piece is left after being eaten alive, there is hope of survival. But does it have any implications for those of us who, as a general rule, do not survive being blown to pieces? If any, the implications are limited. We do not have an organizing center like Hydra (at least not as adults), and so we’re not going to find reassembly quite so easy. Few animals, in fiction or real life, are as lucky as the Hydra, because very few animals can be torn apart and survive.

Share the post "This animal can be torn apart, and will come back together again"

Thank you for posting this! What cool little creatures. I especially like it because it reminds me of the story of Heracles fighting the Hydra, when he cut off one head, another (or in some versions many) would spring up in the same spot. I can see that they look like tiny versions of the mythological Hydra (probably part of how they got their name?), I wonder if they had an ancestor that was larger, not huge but big enough to be noticed and with the same regenerative power that could have started the myth.