Most fauna in the deep-sea rely upon a drizzle of particles of decaying animals and feces. This marine snow is of low food quality as you might expect death and feces to be. Occasionally, deep-sea buffets occur in the form of a large food fall, a nice way to a near complete carcass. My work on chunks of wood on the deep-sea floor represents one type of these smorgasbords. Other large food falls occur in the form of the well-known whale falls. Natural food falls, i.e. scientist not tossing wood or a whales into the deep ocean, are rarely encountered. Only nine vertebrate carcasses have ever been documented on the seafloor. Add to that four more thanks to Nicholas Higgs, Andrew Gates, and Daniel Jones.

Most fauna in the deep-sea rely upon a drizzle of particles of decaying animals and feces. This marine snow is of low food quality as you might expect death and feces to be. Occasionally, deep-sea buffets occur in the form of a large food fall, a nice way to a near complete carcass. My work on chunks of wood on the deep-sea floor represents one type of these smorgasbords. Other large food falls occur in the form of the well-known whale falls. Natural food falls, i.e. scientist not tossing wood or a whales into the deep ocean, are rarely encountered. Only nine vertebrate carcasses have ever been documented on the seafloor. Add to that four more thanks to Nicholas Higgs, Andrew Gates, and Daniel Jones.

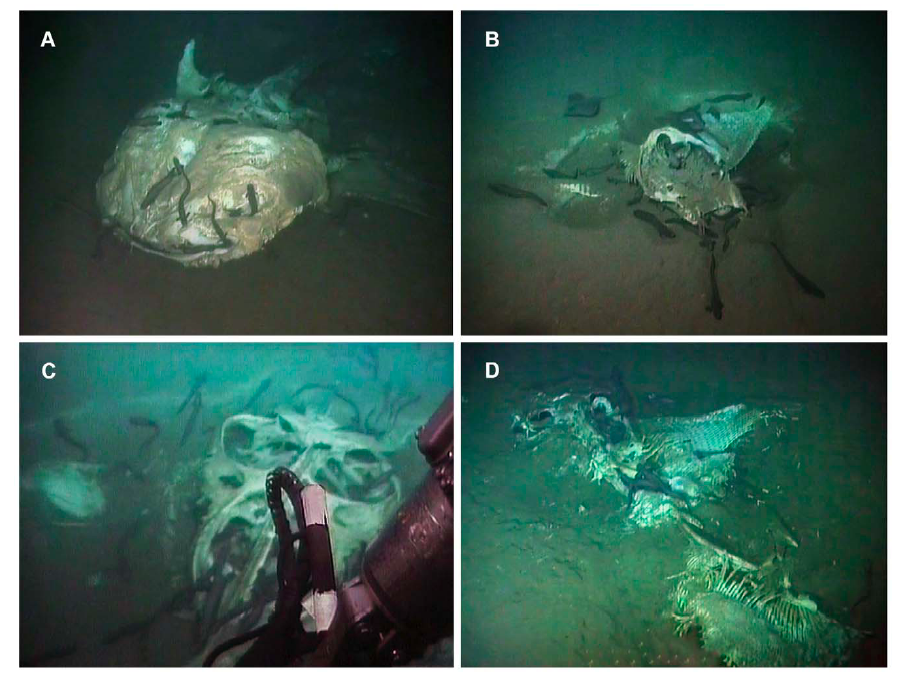

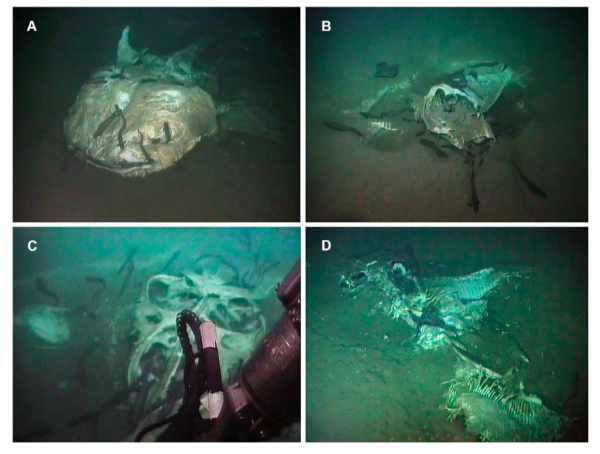

Off the Angolan African coast, these researchers document one whale shark and three ray carcasses at 1200 meters on the seafloor. This is the first time any of these have been documented as deep-sea food falls and only recently have living whale sharks even been documented off Angola.

Despite one of the carcasses being covered in 54 eelpouts, a considerable amount of flesh still existed on the carcasses.

[in prior studies] When presented with elasmobranch and tuna bait on a baited camera trap, scavengers clearly preferred tuna and only consumed the elasmobranch once the tuna was gone…Repeated experiments in this region using [bony] fish as bait showed a 10-fold increase in scavenging rates compared to that when elasmobranch was used.

So why in a food desert like the deep sea would fresh meat not be consumed quickly? Apparently, elasmobranch, i.e. shark and ray, flesh is bit unpalatable and tough to chew. The tough, sand-paper-skin may prove a formidable barrier to scavenger jaws. The high ammonia content of elasmobranch flesh may also be, to say the least, unappetizing. The carcasses may also smell like death and deter other scavenging elasmobranchs.

Other uncharacterized chemicals that are found in rotting elasmobranch flesh (necromones) have been proven to strongly deter shark scavenging and invoke an alarm response, even among different species of elasmobranch. If this phenomenon extends to deep-sea scavenging elasmobranchs, it can be assumed that the Portugese dogfish, Centroscymnus coelolepis, would have been deterred from scavenging the elasmobranch carcasses. This will have severely hindered utilization of the carcasses by other species, since C. coelolepis is the dominant scavenger off the Angola margin.

Yet despite the smell of death and urine, a dead elasmobranch still provides an essential snack in the deep sea. The researchers estimate that these elasmobranchs represent 4% of the total amount food that sinks to the seafloor off Angola in the form of marine snow.

Higgs, N., Gates, A., & Jones, D. (2014). Fish Food in the Deep Sea: Revisiting the Role of Large Food-Falls PLoS ONE, 9 (5) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096016

Share the post "Dead Elasmobranchs on the Seafloor are Not as Appetizing as One Might Assume"