Source: T.Whitty

“I think it’s important to establish, first of all, that Irrawaddy dolphins are jerks to study.”

Not exactly the preface I was expecting.

“One of my esteemed colleagues describes them as, ‘cute, but generally irritating.’ They tend to be boat-shy and will scatter in all directions (popping up hither and thither), they surface low to the water, have relatively tiny dorsal fins, and sometimes will surface and re-submerge without even showing them.” Tara continues sarcastically, “This makes photo-identification absolutely delightful. I have said many not-so-nice things to these adorable critters.”

Despite popular notion, studying dolphins entails it’s fair share of frustrations. No one understands this better than Scripps Institute of Oceanography scientist and premier “waddy” wrangler, Tara Whitty.

Soure: T.Whitty

Armed with her camera and clipboard, Tara scans the waters of Malampaya Sound for signs of her rather elusive study species. Unfortunately, the Irrawaddy’s ephemeral presence is most likely attributed to their ICUN designation rather than their secret plight to evade Tara’s ever-watchful eye. Though I can’t say that for sure.

“Irrawaddy dolphins (Orcaella brevirostris) are a relatively little-studied species of dolphin distributed patchily around Southeast Asia. They occur in riverine, estuarine, and coastal habitats, which puts them in contact with a number of human activities. Though the species as a whole is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List, several subpopulations (i.e., geographically separated groups) are listed as Critically Endangered. Major threats include accidental entanglement in fishing gear, or “bycatch”, as well as habitat degradation (particularly for the riverine subpopulations), pollution, and boat traffic,” Tara explains in her research blog Of Dolphins & Fishers.

As a conservation ecologist, Tara’s research with the Irrawaddy is critical in our greater understanding of these creatures, their role in the ecosystem, and what efforts we might take to recover their rapidly fleeting populations. Yet, the dolphins are merely players in a greater underlying narrative.

Source: T.Whitty

Whether by tradition or necessity, many of the coastally developing nations that encapsulate the Irrawaddy’s home range continue to depend on small-scale and artisanal fisheries. Despite the fisheries being relatively low-tech, they are vital to the livelihood and food security of millions of people. Conversely, these fisheries exhibit the greatest threat to dwindling dolphin populations through accidental capture by fishing gear. Balancing the complicated interface between human well-being and charismatic animal conservation, dolphin bycatch presents a problem not easily remedied.

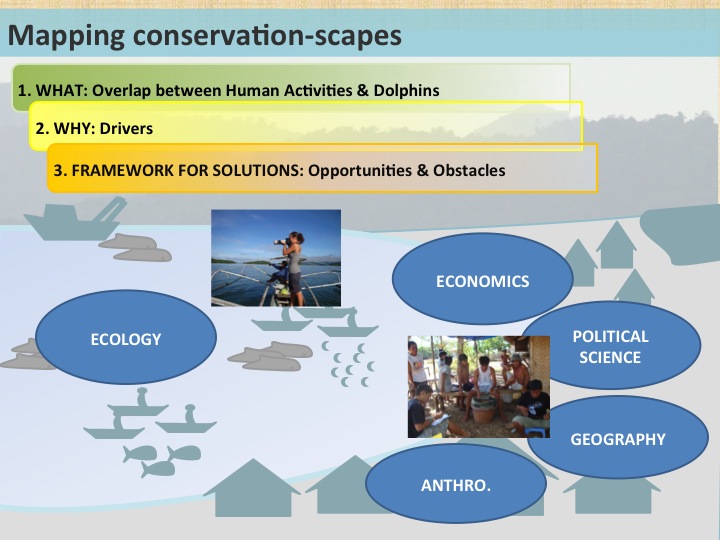

Thus, Ms. Whitty has taken to the business of mapping conservation-scapes. Stepping back and looking at the whole picture, these conservation-scapes consider not only human impact on dolphins, but the social, cultural, and economic factors that drive human-dolphin interactions. Furthermore, her work examines the obstacles and opportunities that exist for fisheries management and marine conservation within these communities.

Source: T.Whitty

Through extensive interviews with the local populace spanning her four study sites (Thailand, Indonesia, and two in the Philippines), Tara compares conservation-scapes across locales to better understand how management might be improved in these places. These household surveys cover topics ranging from fishing practices and local dolphin knowledge to perceptions of marine resource management and governance structure. Now, it would seem that such direct interactions would not bode well for “prying scientists,” however this did not appear to be the case for Tara and her team.

Source: T.Whitty

She fondly recalls, “Often, we were treated with great hospitality – given the best (sometimes only) chairs in the household, treated to snacks and extremely sweet coffee or tea, and sometimes fresh coconuts. I also had several charitable local women offer to find me a local husband: ‘You are married? No? Ah. When do you come back here? OK. I will find some men for you.’”

When not being promised off to the locals, Tara and her interview crew continue to pinpoint potential pathways for improving conservation and fisheries management practices in these areas. With this goal, SAFRN, more formally know as the Small-scale and Artisanal Fisheries Research Network, was founded.

At it’s core, SAFRN is more or less a “support group” for those interested in doing interdisciplinary research within small-scale fisheries. Often times, research that is done in these areas is not cohesive, with multiple projects in progress, but little to no communication between them. Thus, with collaborators from Scripps Institute of Oceanography, San Diego State University, and the Southwest Fisheries Science Center, “SAFRN aims to serve as a hub for interdisciplinary communication and collaboration on methods for studying small-scale and artisanal fisheries, and for elucidating the commonalities and differences across fisheries in different regions where this research is conducted.”

So what does this all equate to? Does Tara’s research on the inter-tangled lives of humans and dolphins end in a happily-ever-after?

“I’ll be blunt: I have serious doubts about whether the dolphins at 3 of my sites are going to make it. They have tiny population numbers, with bycatch beyond the sustainable “Potential Biological Removal” rate. I believe that this represents the situation for many subpopulations of marine mammals, particularly riverine and coastal cetaceans, and thinking about it can be disheartening. I spent a good amount of time feeling discouraged, wondering, ‘What am I doing here? What’s the point?’

Source: T.Whitty

Here are some thoughts that emerged from that process: This particular conservation issue (marine mammal bycatch in small-scale fisheries in developing countries) generally coexists with a suite of other issues that need to be addressed regardless of the charismatic animals, for environmental and social sustainability. Maybe we can’t save these dolphins, but “mapping conservations-capes” at these sites might be able to help improve future management of other issues related to ecosystem health and human well-being.

We need to be candid about conservation outlooks. Not alarmist, not carelessly optimistic, but candid and pragmatic. We will almost certainly lose subpopulations, perhaps subspecies or species, of marine mammals due to bycatch in the coming decades. That is the reality of the situation. Effectively dealing with that reality will require growth in how we approach conservation research. ”

Source: T.Whitty

For the dolphins and many cetaceans that roam this area, the future looks grim. However, Tara does not believe all is for naught. Many of these coastal communities are in desperate need of interdisciplinary data sets that take into consideration the ecosystem as a whole, humans included. Organizations such as SAFRN are needed to streamline this information, make it accessible, and ultimately, utilize this data in a way that implements sustainable solutions.

The Irrawaddy are merely the sentinel species, forewarning us of impending danger, not only in Southeast Asia, but globally. Are we listening?

For more about Tara Whitty’s research and the Small-Scale Artisanal Fisheries Network, visit:

http://artisanalfisheries.ucsd.edu

Special thanks to Tara Whitty, for letting me tell this story for all of you here at Deep Sea News and for dealing with my many, many e-mails. Salamat.

great article! thanks so much for sharing!

Very cool! An entertaining and eye-opening read!