Everyone’s favorite crabs are back in the news! Yeti Crabs! Those deep-sea beasties with hairy claws or chests! A new paper in Proceedings B led by Nicolai Roterman, the only person I know with a Yeti Crab tattoo, reveals the evolutionary past and home of the charismatic crabs. Shamefully, it doesn’t include anything about whether their hairiness emerged during the age of disco. Dancing Yeti Crabs!

Everyone’s favorite crabs are back in the news! Yeti Crabs! Those deep-sea beasties with hairy claws or chests! A new paper in Proceedings B led by Nicolai Roterman, the only person I know with a Yeti Crab tattoo, reveals the evolutionary past and home of the charismatic crabs. Shamefully, it doesn’t include anything about whether their hairiness emerged during the age of disco. Dancing Yeti Crabs!

The group sequences genes from 23 species of marine squat lobsters including for Yeti Crab species. No they are not called squat lobsters because they can squat massive amount of weight like a boss. Squat lobsters, while superficially resembling short lobsters, are actually crabs that are flattened with long tails curled beneath them and most closely related to hermit and mole crabs.

Rather impressively, Roterman’s team sequenced nine gene regions, including two from the ribosomal RNA genes, 5 protein-coding genes, and two from the mitochondria. This sort of genetic coverage first tells the world you’re a total genetic badass and second gives a tremendous amount of power to resolve relationships among  these crabs.

these crabs.

What you get after a set of super fancy computational analyses is how individual species sets of nine genes are related to other species sets. The tree above details those relationships. To give you bearings the tips of the tree labeled Kiwa are the four Yeti Crabs. You can see easily see they form a distinctive cluster, i.e. they are more closely related. The length of the horizontal lines is how much genetic divergence exists between species. So Kiwa ESR and Kiwa SWIR are relatively closely related and diverged relatively recently. These two Kiwa plus K. hirsuta are more closely related than any of them to K. puravida. Likwise, the Kiwa group (Kiwaidae) is more closely related to those species in the Chirostylidae. Those numbers and asterisks on the tree provide two different estimates of confidence in the branching or split at that spot. Numbers closer to 100% and probabilities over 0.99 denoted by ** have more confidence.

What does this tree tell us?!

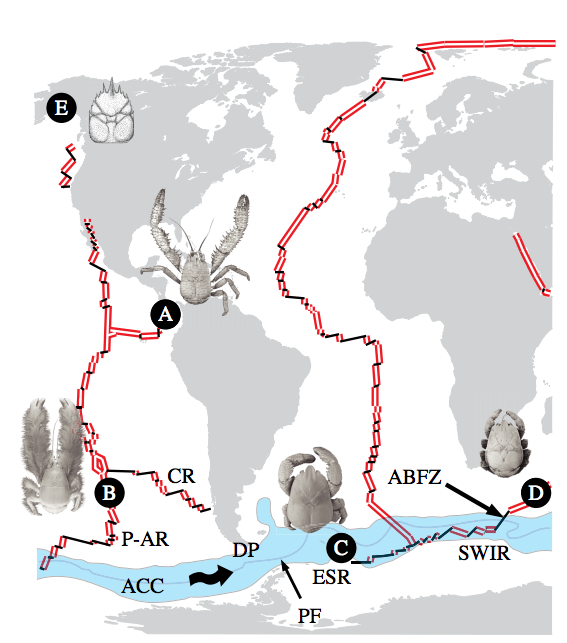

K. puravida is more basal, i.e. the earliest species to branch and the one that goes best in pesto, among the Yeti Crabs, with K. hirsuta being second. In the map below K. puravida (A) and K. hirsuta (B) are both found in the Pacific while Kiwa ESR (C) and Kiwa SWIR (D) are found in the Souther Atlantic. Based on where the basal species are located, the origins of the group are most likely in the eastern Pacific Ocean. The authors suggested that spreading zones in red served as larval highways for Yeti Crabs. Once Yeti crabs reached the Antarctic Oceans they hitched a ride on the Antarctic Circumpolar Current through the Drake Passage that allowed them to colonize the South Atlantic. Given that one of these crabs has the wonderful name of the Hoff Crab, I am reminded of David Hasselhoff swimming.

By calibrating this genetic tree with fossil data we can hypothesize when these splits between different groups and species occurred. The Yeti Crabs most likely split into new species around 55 million years ago after an event name the Paleocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). During this time global temperatures raised by 11˚F. The warm oceans caused many marine organisms to go extinct. The post PETM world would have contained many opportunities for an enterprising hairy chested crab.

By calibrating this genetic tree with fossil data we can hypothesize when these splits between different groups and species occurred. The Yeti Crabs most likely split into new species around 55 million years ago after an event name the Paleocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). During this time global temperatures raised by 11˚F. The warm oceans caused many marine organisms to go extinct. The post PETM world would have contained many opportunities for an enterprising hairy chested crab.

C. N. Roterman, J. T. Copley, K. T. Linse, P. A. Tyler, and A. D. Rogers The biogeography of the yeti crabs (Kiwaidae) with notes on the phylogeny of the Chirostyloidea (Decapoda: Anomura)Proc. R. Soc. B August 7, 2013 280 1764 20130718; doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.0718 1471-2954

What is the function, if any, of the ‘hair’?

For the Hoff Crab, the chest hair appears to be a convenient spot to farm its symbiotic bacteria.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-22952728#

And, of course, more chest hair = more badass.

Thanks Jennifer.