Many animals do not spend their lives entirely in saltwater or freshwater choosing rather to fully explore the world around them. These species are referred to as diadromous from the Greek diá meaning across, through, between and drómos meaning running or course. Some animals, like freshwater eels, start their lives in streams and rivers only to explore and make love in the open ocean. For others, like salmon, sturgeon, and smelt, the journey is reversed and breeding occurs with a little less salt. Then there is a third group and their existence is an evolutionary conundrum.

Amphidromous animals grow up into adults and make sweet, sweet love all in freshwater. But the hatchlings, those cute, meek, little larvae, are kicked downstream to the big and dangerous ocean. Of course they could linger around, but without salinity, their development runs askew and potentially could produce and ear out of their little larval backs. After proper maturing, these juveniles return back to freshwater.

The fish, snails, and crustaceans of freshwater streams on islands are typically amphidromous. How else would they get there? Indeed, some larvae of these species can spend three-quarters of a year in the open ocean. However, a hitch exists in the South Pacific. Freshwater is rare on islands in this region because it requires a high enough volcanic peak to generate rainfall. With this rarity of streams, long distances occur between suitable freshwater habitats. Combine this with a tough ocean favoring death by predation and that bastard diffusion scattering larvae, an amphidromous lifestyle may not be the winning evolutionary ticket.

Our old friend natural selection should favor keeping the young’ins close to home.

Yet, the conundrum of amphidromous species on South Pacific islands still exists. Freshwater Nerites, an intriguing family of snails containing members that are freshwater, marine, and somewhere in between, are one such puzzle. Neritina canalis and Neripteron dilatatus both possess larvae that venture into the open ocean. Adults of Neritina prefer hiding under rocks in riffles while Neripteron prefers rocks where they can take in the sweet smell of estuary.

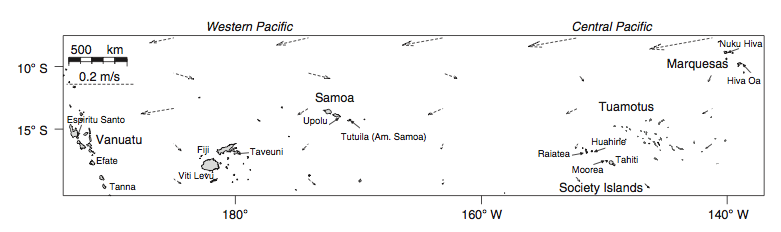

Both species occur across the South Pacific from the Philippines to the Marquesas and Society Islands. Across that roughly 5,000 kilometer distance, roughly the width of the United States, populations are not genetically different. If the individual populations did not trade individuals and their genes, then slowly over time a different set of mutations would accumulate in each population. This genetic drift would lead to unique genetic fingerprints for every population on different islands. In both of these species, genetic fingerprints were identical in island populations 1,000 of kilometers distant. In addition, both snails are able to delay larval metamorphosis and spend longer in the ocean than many marine species (>50 days in N. canalis and >115 days in N. dilatatus).

Of course the simplest explanation is that larvae are regularly traded across the entire the South Pacific.

Of course the simplest explanation is that larvae are regularly traded across the entire the South Pacific.

So why would the risky amphidromous lifestyle be favored. Living in an island stream is no cakewalk. Streams are short with variable flow. Seasonal and annual fluctuations in rainfall and temperature may reduce the amount of water to live in. Add in the potential of frequent erosion from those same high elevation volcanoes and let us not forget the volcanoes themselves…and well species are screwed. The winning ticket should be getting those larvae far away from the hellhole you grew up in.

Damn predators, diffusion, and rarity of habitats. Snails are playing evolutionary craps and their rolling 7’s and 11’s.

E.D. Crandall, J.R Taffe, and P.H. Barber (2010) High gene flow due to pelagic larval dispersal among South Pacific archipelagos in two amphidromous gastropods (Neritomorpha: Neritidae). Heredity 104, 563–572; doi:10.1038/hdy.2009.138

One Reply to “The Oceanic Travels of Freshwater Snails”

Comments are closed.