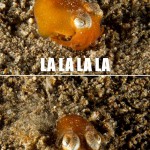

Most folks I know aren’t shy about crunching into a nice red American lobster and dipping that white flaky meat in some molten butter, and who can blame them? But what if the lobster in question looked like this:

What you are seeing is the (not very creatively named) shell disease of lobsters, a disfiguring condition that has become a major problem for both lobsters and lobster fishers in New England waters, especially off Rhode Island and the eastern end of Long Island Sound in New York. Affected lobsters have one or more lesions on their shell that look a lot like cigarette or acid burns. They are often black and can sometimes coalesce into extensive areas of eroded shell that may become paper thin. The lesions seem to concentrate over the back of the lobsters in the middle of the carapace and, curiously, the lesions are usually somewhat symmetrical. If there is a cigarette burn on one claw, then there is usually a matching on the other claw.

Before I started my affair with whale sharks, I used to study lobsters once upon a time, and recently a couple of shell disease papers have come out that I’m a co-author on. These were part of a lobster shell disease initiative coordinated out of Rhode Island Sea Grant. One paper, authored by Sheryl Bell addresses the community of bacteria that lives on the shells of lobsters, while the other by Margaret Homerding looks at how the immune system of the lobster responds (or not) in shell disease cases.

To understand shell disease it helps to have a look at the shell itself, because it’s amazing stuff. An excellent paper by Raabe and colleagues describes it as “structurally and mechanically graded biological nanocomposite material” that shows great strength and some flexibility; their paper contains this wonderful figure illustrating their point:

Another of Raabe’s papers shows the layers a little more clearly, and they can be nicely related to the layers in the paintjob on a car.

Starting from the outside, just like a (nicely detailed) car there is a very thin veneer of a waxy sort of coating. Under that are several layers of outer shell or “exocuticle”, most of which is calcified. These would be like the top coats of paint on the car. Under that is a thicker series of layers of inner shell or “endocuticle”, some of which is calcified and some of which hasn’t got there yet; this stuff is more like the primer layers on your car’s paint job. The whole lot grows outward from a thin layer of epidermis, the true “skin” of the lobster, which is just a few cells thick and is all the separates the tasty bits from the outside world if it weren’t for that crunchy shell.

Just because the shell of lobsters is hard doesn’t mean it is inert. Indeed, research is proving that the shell is very much alive and a dynamic tissue. That thin surface layer of wax for example, is probably secreted onto the surface through pores that penetrate all the way down to the epidermis, and there are certainly all sorts of sensory hairs and organs that penetrate the shell and connect the soft organism inside to stimuli in the outside world.

The shell is also home to a diverse community of bacteria and single celled organisms that live and roam on the surface, playing out their teensy microbial dramas on a vast calcified Serengeti. This is important because it is with this wax layer, these pores, and those bacteria that shell disease seems to start. The first change noticed at the onset of the lesion is the loss of the wax layer. After that, bacterial populations seem to multiply and penetrate down into the pores. Then the lesion spreads, undermining the adjacent exocuticle as the bacteria spread through the layers, stripping out the calcium and leaving the shell weak and papery. In bad cases you can poke your finger right through the shell and into the body. It’s often said that shell disease is mostly cosmetic, but I don’t think so.

All of that brings us to Sheryl and Margaret’s papers. Without going into too much detail, Sheryl used DNA methods to show that many of the usual bacterial community members are present but that some are more abundant in lobster lesions. Do they cause the lesions? That’s not so certain; even though they are more common we have to be wary of false correlations and it really requires the fulfillment of Kochs postulates to confirm which bug is responsible. Margaret used a toolkit of immune function tests to show that lobsters from affected areas did not have as robust a response to challenge as did lobsters from unaffected areas. The question there is: cause or effect? Are these lobsters sick because their immune systems are compromised, or are they compromised because they are sick? OR are they sick AND immune compromised due to some third unknown cause.

These questions remain to be answered, but one thing is for sure. Shell disease in lobsters is not a simple problem with a single easily-identified cause. Like so many wildlife diseases, it is a complex and multifactorial problem that, despite the best efforts of the Sheryl Bells and Margaret Homerdings of the world, we are only just beginning to understand.

References:

D. Raabe, C. Sachs, P. Romano. The crustacean exoskeleton as an example of a structurally and mechanically graded biological nanocomposite materialActa Materialia, Volume 53, Issue 15, September 2005, Pages 4281–4292 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2005.05.027

S.L. Bell, B. Allam, A. McElroy, A.D.M. Dove and G.T. Taylor. INVESTIGATION OF EPIZOOTIC SHELL DISEASE IN AMERICAN LOBSTERS (HOMARUS AMERICANUS) FROM LONG ISLAND SOUND: I. CHARACTERIZATION OF ASSOCIATED MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 31, No. 2, 473–484, 2012

M. Homerding, G.T. Taylor, A. McElroy, A.D.M. Dove and B. Allam, INVESTIGATION OF EPIZOOTIC SHELL DISEASE IN AMERICAN LOBSTERS (HOMARUS AMERICANUS) FROM LONG ISLAND SOUND: II. IMMUNE PARAMETERS IN LOBSTERS AND RELATIONSHIPS TO THE DISEASE . Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 31, No. 2, 495–504, 2012

Nice account of the ‘skin/shell’. What pathogens have been excluded so far?

Excluded? Well there are many that have not been found. It may be easier to say which ones have been most positively correlated with the lesions. In a different study Andrei Chistoserdov identified a new species he called Aquimarina homari that was in every lesion. Again, its correlation, not causality because Kochs postulates have not been fulfilled. Read more here: http://www.vims.edu/~jeff/biology/2012%20Shields%20impact%20of%20diseases%20on%20crustacean%20fisheries.pdf

Maybe Hurricane Sandy has something to do with it. Tons of pollution and pesticides probably made their way and are now on ocean floor. Just my guess, but hope they find a solution.

Maybe it’s equal to Lobster psoraisis or vitiligo. Coconut oil seems to help human autoimmune diseases as well as aloe vera juice (modulates the immune system). Maybe Mr. Pinchey has leaky gut syndrome. In any case I hope Pinchey and Scuba Steve get better so we can all enjoy a bite at Red Lobster.

Are these “diseased” lobsters culled from the food chain? Are they harmful to Humans? How can we tell when we sit down for lobster dinner say in Kennebunkport? The ocean is a fairly large bucket.I find it difficult to believe that it’s polluted.