My tall-ship-sailing buddies at Sea Education Association are headed out for a special Pacific plastics cruise tomorrow aboard the 134-foot brigantine SSV Robert C. Seamans. (Disclosure: I am totally biased cause I’ve sailed with them twice and think it is the best thing ever. Also, they’re collecting samples for me on this cruise. Thanks guys!) From the press release:

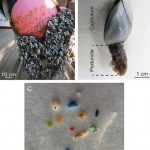

During their 37-day cruise, the crew of the Woods Hole, Mass.-based sailing oceanographic research vessel Robert C. Seamans will explore a region between San Diego and Honolulu, popularly dubbed the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”, where high concentrations of plastic debris accumulate. Floating debris washed to sea by the March 2011 tsunami in Japan will also be drifting in the area, based on predictions from computer models and recent observations.

This year we have introduced a K-12 outreach page to our expedition website, where students in ten partner schools from around the country will submit questions that the expedition team will answer from sea. A major goal of this expedition is outreach and education to schoolchildren, educators, and the public.

Devil’s advocate question: So we know that floating ocean plastic eventually washes up (months, years, or decades later). We also know that without extremely good luck there is no way of knowing the original source of a broken piece of plastic. So I wonder, what is the benefit of expensive & dangerous open-sea scientific exploration? If the question is whether plastic is a vector for invasives or toxins, can’t that be discovered on a day cruise just off a dry-land home base?

From the above it sounds like raising awareness is a big key… But again, doesn’t a plastic-laded albatross carcass on an atoll 2000 miles from mainland raise the awareness just as well?

Is the problem funding? I can see how it might be more exciting and sexy to pitch & fund an open-ocean adventure… But does the science actually benefit from spending all that extra money and adding all the extra risk?

You know I love it when you’re saucy, Harry. And the answer is no, you can’t collect these samples with a day cruise – you have to go to where the plastic is, which in this case is usually about 1000 miles away from any land. For SEA’s microbes-growing-on-plastics project, they have to carefully preserve the plastic pieces in a variety of solutions to preserve RNA, DNA, etc, or they have to freeze them. They can’t use something that’s been sitting on a beach or in a totally different water mass, because the microbial populations will have changed. Same thing for my zooplankton work – you get a bit of the subtropical zooplankton community off Hawaii, but not off California! You really have to go 500 miles or so offshore to get the true subtropical zooplankton.

Raising awareness is a different story, and something that I’ve started thinking about how to actually measure. (This is Karen James’ nefarious influence.) I agree that we need to be more critical of projects that solely aim to “raise awareness” – but this one is mostly about the science.

For straight-up NSF science funding, the adventure-time stuff doesn’t matter as much, but it matters a lot for NGO funding. However, that’s not what’s going on with SEA – they actually need to get their ship to Hawaii for other logistical reasons, so they thought they’d do this cruise along the way.

See? -This- is why I love asking questions here! Because the answers always leave me feeling like I knew more than I did. Thanks!

Very interesting about the changing microbes — raises neat Qs about if/how nasties on plastic in one part of the world can get to other parts of the world. Also, I’m guessing it’s useful to know which baddies can survive long trips.

I do still wonder how many inquiries that are done in the open ocean could be done instead 20 miles offshore of, say, Oregon. The huge amounts of plastic wash-in there prove that ocean-borne plastic’s in easy reach.

There might be a lot of trash on Oregon beaches, but in the only study off Oregon that I know of that looked at pelagic microplastic (Doyle et al. 2011) they didn’t find much at all.