In Aesop’s The Tortoise and the Hare a slow-moving but determined tortoise defeats an obnoxious and speedy hare, who decides to nap mid race. The moral of the fable is generally taken that slow and steady wins the race or alternatively over-confidence loses the race. However, perhaps Aesop meant to highlight a common biological principal. Bigger animals travel at faster speeds.

If we assume Aesop was speaking of typical or averaged sized hares and tortoises then the tortoise would have been bigger. Although, I acknowledge that the largest of hares, the European Hare, capable of weights around 11 pounds, is larger than the smallest of tortoises, the Speckled Cape Tortoise just shy of 6 ounces. In general across the animal kingdom, the larger in size, the faster an animal can travel from point A to B.

A horse can travel faster and its endurance will carry it much further than a small running mammal. Among the runners, the migrants who range farthest are the largest ungulates, the caribou of the tundra, and the bigger antelopes of the African grasslands. –Calder 1984

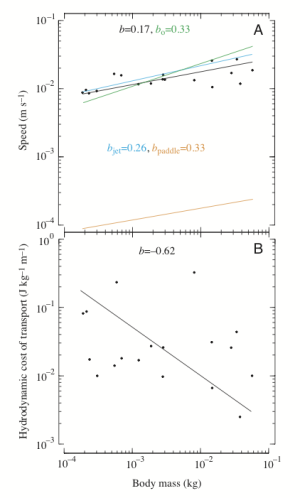

In the common moon jelly, bigger jellies can achieve greater swimming speeds and doing so is less costly than for their smaller brethren (see figure). Large animals not only run and swim faster, but also take fewer, longer strides and strokes making them more efficient biological machines. Even the abalone, not widely viewed as a sprinter, gets faster the larger size it obtains, and is faster than its smaller molluscan relatives.

But yet this rule starts to break down the more closely we examine it. Imagine coaching an NFL team where you replaced all of your backs and receivers with the heaviest players you could find. You would likely, no matter what biological rule to cite in your defense, not last the preseason. In the NFL, 40-yard dash times for those beefy defensive tackles range from 4.5-5.54 seconds and for the even larger centers well over 5 seconds. Compare these to times for the smaller running backs (4.4-4.88) or the relatively light wide receivers (4.36-4.74). Even our fable of the tortoise and the hares is a horrible example of this so-called biological rule. Some hares can reach speeds of 45 miles per hour, light speed compared to the 0.17 miles per hour of a tortoise. All this suggest that life is more complicated than simply a poorly conceived bigger faster rule

Like many other animals urchins and starfish typically gain speed with girth, a NFL-esque exception does exist. The trying-to-hard-to-be-different bat star crawls slower the bigger it gets. A 1.7-ounce bat star will crawl at a speedy 0.004 miles per hour. A 5-ounce weight gain slows its transit by half. So why are fat bat stars so slow?

Like other starfish and urchins, the bat star moves on tube feet. These hundreds to thousands of small tubular projections are connected to a hydraulic system that allows each tube food to individually suction to a surface. By alternating tube foot sucking, a starfish can be propelled in a particular direction. When a bat star gets brawnier, the number of tube feet do not increase in proportion. In other words, each tube foot has to carry more weight and thus slowing everything down.

Thus it is not just how much you move but how you move it.

Share the post "Understanding How Hares and Big Lineman Lose Races Through Sucking Feet"

Small correction from a football fan: Centers weigh less on average than offensive guards, offensive tackles, and defensive/nose tackles. See here: http://www.pro-football-reference.com/blog/?p=493

I’ve got another sea star illustration for you, in the opposite direction. Sunflower stars have up to about 25 arms, and big individuals have many thousands of tube feet. Each tube foot can only push off so hard, in any sea star species; tube feet are about the same size & power (roughly). But sunflower stars, with so MANY tube feet, are the fastest sea stars at least in my area (Pacific Northwest), if not the world. A meter per minute may not sound like much, but it’s a quite impressive gallop for a sea star.