A paper by Marc Nadon and colleagues from U. Hawaii and U Miami RSMAS has been getting a good bit of press lately (see here and here and here), and rightly so, it’s an interesting and important subject. They studied populations of reef sharks in the Pacific and attempted to reconstruct what the “starting” populations would have been before human activities began to affect them and before anyone thought to monitor reef shark populations. Sort of a reverse forecast. Their models indicate that many reef shark populations like grey reef sharks and white tip reef sharks may have dropped as much as 90%. This is important because most studies up to this point have focused on pelagic sharks like makos and tiger sharks, which have been fairly obviously decimated by the finning trade and other problems. To learn that declines in smaller, reef-associated sharks are similar is fairly grim news.

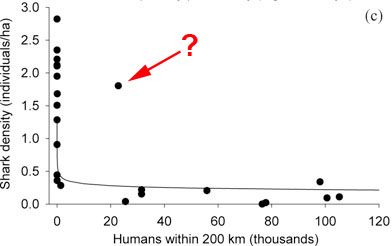

Sometimes when you read a paper, one statement or figure sticks out and in the Nadon paper it’s their Figure 3(c), and here it is:

In this figure Nadon and his colleagues show the relationship between the density of sharks measured by towed diver surveys (how do I get THAT job?), and the number of humans living within 200km of the sampling site. A couple of things jump out at me in this interesting figure. The first is that the relationship is heavily, heavily skewed. It’s so skewed that plotting a curve on it actually seems fairly pointless. What we appear to be dealing with is a sort of binary situation. If there are no people living near the sampling site, then shark numbers are in the 0.5-3.0/ha range, but if there are people living within 200 klicks – any number of people – then there are effectively no sharks present. I might have tried a log scale on the x-axis to give better resolution at the low population end, but there are few data points there anyway, which is a bit frustrating but probably just reflects the difference between populated and unpopulated islands. There’s also one outlier, which I marked with a red arrow; I really wish they’d labeled that one, because it’s so different from all the others and outliers are always interesting. (aside: I think it was Steven Jay Gould who said that if you want to know how normal folks think, one thoughtful deviant will tell you more than a thousand solid citizens)

A binary relationship between the abundance of sharks and that of people is effectively saying that they are mutually exclusive: people = no sharks, no people = sharks. That’s a pretty disappointing thought. Of course it doesn’t tell us the mechanism, or even if the relationship is causal in any way, but I don’t think it’s a huge leap to suggest that human impacts on reef diversity and function in general, especially overfishing, are likely to put a pretty negative pressure on reef shark populations. If this proves true then it may not be that humans are doing anything to the sharks per se, just not looking after the reef generally, and that is being reflected at the top trophic level. However you slice it, their results are more grist to the mill that we need to be doing a better job with the conservation of both reefs and sharks, because sometimes those two things are inextricably intertwined.

The Nadon paper is open access; you can read it here

What is perhaps most upsetting about this paper is that it’s not the first – sadly, it concurs with a growing body of literature that says shark populations have been plummeting, and continue to do so (see the refs in my post on this paper, as well as some sobering statistics from the HIMB community education blog).

(from page 10, emphasis mine)

“Also available online is information on the correlation coefficients between covariates (Appendix S7), model parameter estimates (Appendix S8), and the island-level summary data set and modeling results (Appendix S9). The authors are solely responsible for the content and functionality of these

materials. Queries (other than absence of the material) should be directed to the corresponding author.”

Frustratingly, appendix S9 is not included in the supplementary information .doc at the link provided on Wiley’s site… Looking at figure 3c, the outlier has a shark density of ~1.8. A good candidate might be one of the ‘Mariana Islands- West’ sites. At a guess and a glance at Google Maps, these were located on one of the ridges which rise from the Phillipine Sea running N/S from about 50 miles W of Saipan to ~150 miles W… a 200 km ring around the southern most one might be clipping Saipan or Tinian.

You appear to be right, there’s no S9 in the supporting documents, even though it is listed. How odd.

I agree, it’s a pity that outlier is interesting. Might it be Galapagos? Quite a lot of reef shark, despite humans?

Julia Baum pointed me to your blog and to this interesting discussion. The outlier reef on fig. 3c is Sarigan in the Mariana Islands. It is the southernmost surveyed island of the remote, sparsely habited, northern Mariana region. Since it is located 170 km away from Saipan (pop. 48,000), it is just within the 200 km limit of our proxy variable for human-related effects (i.e. human pop. < 200 km).

Reef shark density around Sarigan appears fairly healthy and it is likely that the island is located sufficiently away from Saipan to avoid strong fishing pressure (on sharks and their prey).

The 200 km limit for our human influence variable general works well, but this is a case where maybe a lower limit might have worked better. The 200 km-limit was based on the distance a vessel can cover in 12 hours at 9 knots (i.e. a day trip).

About the shape of the human vs. shark density relationship: it is indeed almost binary in nature. Most of the decline in reef shark occurs before 1000 humans within 200km and the scale of fig. 3c doesn’t represent this well (see appendix S4 for a better representation).

Also, appendix S9 is now available online. It was simply omitted in the original online posting.

Bahamas?

Hi Marc, Thanks so much for chiming in; its always nice when the original authors join the conversation. So, my essential conclusion wasn’t far off, then? ANY number of people seems to be too many. Do you also think that its an indirect effect from general reef decline, or might there be another mechanism at work here?

Thanks also for the S9 correction, I look forward to seeing it.

You’re essentially correct: it only takes a hundred or so people around a reef to get shark densities down ~50%, according to our model. However, as you pointed out, there isn’t a lot of data points between 20 and 20,000 humans < 200 km, so we have to be cautious about interpolations in that part of the curve.

The reason there isn't many data points there is that populated areas in the central Pacific usually have large, very concentrated, populations. In other words, there isn't a smooth, decreasing, gradient of human abundance as we move away from, say, Saipan. It's almost all-or-nothing in terms of the 200 km limit of our proxy variable.

We believe the reason for reef shark decline is a mix of direct removal (targeted, by-catch, or catch-and-release fishing mortality) and the heavy exploitation of reef fish around populated islands (~70% of their diet). Many papers have pointed out that reef sharks have slow reproductive cycles and it doesn't take a massive commercial fishing operation to get negative population growth. Even a small negative trend, year-after-year, decade-after-decade, will eventually lead to very low population numbers.

Thanks very much for that additional info Marc, it really helps shed light on the situation. Do you know if your info was any part of the recent conversations in Fiji about creating a shark sanctuary?

I hadn’t actually heard about the Fiji shark protection efforts. I sincerely hope the results from our study will help promote better management and grassroot initiatives.

Glad I could help!

Bula from Fiji.

I can confirm that this paper has been shown to the local authorities and that it did indeed prove very helpful.

Great post BTW!

I’ve referenced it here where I’m asking some further and possible completely asinine questions.

DaShark: yourself and others raise good points on your blog. I posted a long (possibly rambling) reply.

Great to hear the article is getting some attention from local managers!

I used to see lots of big sharks on the nine mile bank off Point Loma ten years ago. Now throwing sardines there just makes a long swim home for them. Sharks: more deck chairs for the Titanic?

Cliff