This is a guest post from Alexis Rudd , who is a doctoral student at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology on the island of O’ahu. Her research uses sound to study the distribution and behavior of dolphins and whales in Hawaii, in partnership with Young Brothers interisland shipping company.

, who is a doctoral student at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology on the island of O’ahu. Her research uses sound to study the distribution and behavior of dolphins and whales in Hawaii, in partnership with Young Brothers interisland shipping company.

It seems as though most people have some sort of cultural guilt; we feel bad about not calling our parents regularly, about forgetting our brother’s birthday, or we chow down on half the gallon of ice-cream while watching the season finale of Glee (yes, I cried). I have an additional guilty secret – I am one of the few marine biologists that actually studies dolphins. And not cold-water dolphins either – dolphins that frolic under tropical Hawaiian sunsets. It really is a secret, at least from casual acquaintances. When my dentist asks me what I do, I usually tell her I spend a lot of time on the computer. When the guy next to me on the airplane strikes up a conversation, I generally tell him I study underwater sound.

Why all this guilt? Well, when you think about all of the millions of amazing creatures in the ocean, dolphins make up a very very tiny percent. And yet, it seems as though they get the majority of the love. Everyone loves dolphins, but there is so much more out there that deserves our love, respect, and interest. I mean, there are tunicates build their own house every day and are one of the inspirations for the alien in Alien! How cool is that?

So, if I feel so guilty about cetaceans (the group that includes dolphins and whales), why am I doing it? Well, despite the love, we really don’t know that much about whales and dolphins. We don’t know where they are most of the time, we have only a hazy idea of what some of them are eating, and we don’t know a lot about their breeding habits. No one has ever seen a humpbacked whale, well… hump. A lot of cetaceans are in big trouble, like the North Atlantic Right whale and the Yangtze River Porpoise. The ones that are in trouble (like almost all other endangered life on earth) are endangered because of humans. North Atlantic Right Whales get hit and killed by big ships. Yangtze porpoises, which have to be one of the cutest animals ever, are being polluted and dammed into oblivion, just like their neighbors, the Yangtze river dolphin, which is now extinct. The beautiful vaquita porpoise is among the 50 most endangered animals in the world. So yes, there are a lot of other fascinating things to study in the ocean, but there are a lot of good reasons to study dolphins, too. Also, I love them, even if admitting it can be like admitting I like Twilight (which I am SO not admitting).

OK, enough about the dolphin-guilt. How did I become involved with cetaceans, and what’s it like to study dolphins in a place like Hawaii? It was a complete accident that I became involved in cetacean biology. When I was an undergraduate, I did research on sea stars. After graduation, I applied for a field course in invertebrate biology (basically the opposite of cetacean biology), but it was full, so I ended up in a class on marine birds. A broken skiff and a Coast Guard rescue later, and I was doing my class project on the association between marbled murrelets and gray whales. The class project led to an internship, and the internship led to a place in the Marine Mammal Research Program at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology.

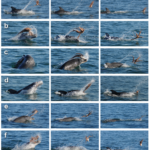

My specific area of study is Marine Bioacoustics, with an emphasis on Passive Acoustic Monitoring. This basically means that my research involves listening to dolphins and whales and then using their sounds to figure out where they are, what species they are, and what they are doing. Acoustics are an extremely useful tool for studying cetaceans, because they spend the majority of their time underwater where you can’t see them. I spend about three days out of 14 on a tugboat, which travels from Honolulu to the Big Island of Hawaii or the island of Kauai. During the daytime, I stand up on the deck and look for cetaceans.

This can be pretty difficult, because the waters in Hawaii are comparatively rough. At night, the waves hit the side of the boat like the slamming of a large metal door, and bounce me up and down on my mattress like it’s a trampoline. Depending on the weather, I will see zero to three groups of dolphins a day. I see a lot of flying fish and birds, and an occasional manta ray, but most of the time it is waves, waves, and more waves. I actually never got seasick until I started going out on the tug boats, but it has been ROUGH out there a few times. I find the best thing to do is park myself in my bunk, breathe deeply, and avoid eating raw asparagus.

When I am on shore, I spend most of my time on my computer, writing programs to deal with the enormous amounts of acoustic data (sound recordings) that I have collected. Some of my time is spent on building electronics, fixing broken electronics, and looking at papers by other researchers. When I am lucky, I get to spend a week or two collaborating with other researchers, which is always a privilege. Through these relationships with other researchers, I have had some incredible experiences. I’ve tracked down a humpback whale by the smell of its breath, and watched false killer whales hunt.

In the end, however, marine mammals are only a very tiny piece of the whole ecosystem that makes this world so beautiful. I would encourage anyone who is remotely interested in marine mammals to also look around at other marine (and terrestrial) life. There is a great deal of beauty worth saving, and it is not just dolphins that are beautiful.

So You Want To Study Dolphins…

Many people think that studying dolphins means you work at Sea World teaching dolphins to jump through hoops. Very little actual research comes from teaching dolphins to amuse people, although training can be invaluable in other contexts. Training is how we know what a dolphin hears and how it manages to hold its breath for so long.* The main objective of marine park shows is to entertain, and to make money. Training dolphins to let you hug them and ride on their backs isn’t science, and it doesn’t tell us anything new about dolphins or help us to protect them in the wild. A dolphin show has about as much to do with real marine biology as a birthday party pony ride has to do with a cattle roundup.

If you REALLY do want to study dolphins, here are a few tips. In school, you should study math, statistics, computer programming, or genetics. Do you absolutely hate this stuff? So did I, when I was in high school and college. However, it is incredibly useful to have these skills and will give you an edge over all the thousands of other people who love dolphins but have no technical skills. People often ask me how they can get paid to go out to sea and look for dolphins. The answer is not something that they want to hear: you need experience. How do you get experience? You work for free, and you do an absolutely excellent job of it. There are a lot of researchers out there who take unpaid interns for dolphin and whale research. These interns typically do a mixture of work, ranging from the very exciting (photographing whales from small boats) to the very boring (matching those photographs against thousands of other photographs). Generally, it is about 3% exciting and 97% boring, percentages that tend to hold true for cetacean research in general. An internship is like a medieval apprenticeship – sure, you are unpaid and work hard, but you are getting real experience with a master of the craft. If you think having new clothes and a good salary are very important, dolphin research is probably not for you.

Speaking of those tropical sunsets, I just missed another one because I was too busy writing computer code.

*This sentence was added after the post went live to clarify what research can be done with captive dolphins. – MG

Share the post "Guest Post: True Confessions of a Dolphin-Loving Marine Biologist"

I got your site off twitter. I would love for you to speak about conservation on http://www.invertplanet.com. This is an open invitation. Take a look at the site, and you will get your own section to discuss your views and findings.

All the best,

J-P

I don’t think we should be too quick to judge the research done on dolphins in aquariums and marine mammal parks. Pretty much everything we know about them has been informed at some point or another by aquarium-based research, particularly in the fields of clinical veterinary research, sensory biology and behavioural studies. These projects are different from and very often complimentary to the work done in field settings, which usually focuses on natural history and population ecology. Many marine mammal institutions are involved in field research programs and collaborate freely with non-aquarium scientists, so the distinctions between aquarium and non-aquarium research are artificial anyway. Also, it’s not safe to assume that all aquarium dolphin programs are designed to make money; many such facilities are non-profits including both the aquariums I have worked at, both of which housed dolphin collections. If you make these assumptions about aquariums and aquarium-based research, you’re falling prey to the exact same stereotyping behaviour that your post sets out to discourage.

Love this! If I may, it reminds me of another big conversation happening in a completely unrelated field — British archaeology. Folks studying Hadrian’s Wall often take a lot of flak from other archaeologists. The Wall is of course iconic, it’s beautiful, everyone knows about it, it’s been studied the most. And the argument is: “There’s so much more amazing stuff to study, why waste your effort on that??”

The compelling counter-arguments are much like yours: because we still don’t really know that much, and because it’s highly threatened and parts are in danger of being loved to death. Which would be a huge loss, as the unpopulated central region still preserves so much of the interaction between artifact and landscape that’s usually been bulldozed away in other regions.

With cetaceans as with the Wall, it may be exactly because they’ve been studied so much that it’s worth it to keep studying them. To get at the deeper, more elusive, bigger answers about them that might help illuminate work on other creatures & ecosystems.

Anyway, really liked the post.

Para_sight: Good point, and I am afraid I didn’t make that more clear. It’s been clarified. An assumption that many people in the public make about dolphin research is that it follows their own experience with dolphins, and this experience centers around shows and swim with dolphins programs. I work with several people who are involved in very amazing captive animal research, sometimes at aquariums, and aquariums can be a valuable resource for cetacean science.

I love to read about your marine studies. I used to SCUBA dive and take video with my underwater camera. I was studying animal behavior of everything I saw. I learned more from observing than from a book. The creatures accepted my presence, and I could move freely among them. This was not a job, it was just fun to learn.

I thought you might appreciate this. When I showed one of my youngest daughters the vivavaquita website, she fell in love with the lil’ critters. Granted, when I was her age, I was all over the 599.98 shelf (marine mammals, at the time) at the elementary school library.

Today is a snow day. My daughter came up to me and asked “Daddy, can I do a project about vaquitas today?” :)

Awwww, that’s so great!!! You just made me tear up a little. :)

Vaquitas are seriously under-represented and under-loved. What a cool kid!

As a follow up, this is how I found my youngest daughter, tonight: https://fbcdn-sphotos-a.akamaihd.net/hphotos-ak-ash4/423398_3412290316808_1556535430_2946044_1278471690_n.jpg