Personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures-F. Scott Fitzgerald

Quirky, sheepish, fun-loving, lethargic, energetic, aloof, courageous, sensitive

You might invoke these words to describe your friends and family. Indeed, you recognize them all by their distinctive personalities. You may even use these terms to describe your beloved dog or cat. But it is hard to imagine talking about an invertebrate and describing their personality. Although, I admit I do find sponges a bit aloof. That may be more me than them.

Anemones are not exactly a top pick when it comes to choosing an invertebrate with personality. Like most, you would probably pick a cephalopod. Rightly so given the large and complex brains of cephalopods compared to other invertebrates. The brain to body weight ratio is higher for cephalopods than any other invertebrate. Cephalopods probably also have more personality than some dogs, especially my former roommate’s dog who only slept and ate cat poop. There is more than ample neural fodder in cephalopods for some individuality.

But an anemone? Please! The nervous system is not centralized, i.e. no brain. Anemones do not possesses any specialized sense organs. The nerves they possess are among the simplest in the animal kingdom. Anemones are just a few specialized cell types from being an aloof but otherwise nondescript sponge. Sorry sponges.

Personality is when an individual expresses a consistently different behavior despite the situation or time compared to other individuals. And despite their rudimentary neural systems, anemones have personalities. When disturbed, anemones will display a startle response in which they will retract their tentacles and cover their oral opening. Mark Briffa and Julie Greenaway shot 3 tablespoons of water at the anemone Actinia equina, repeatedly, to illicit this startle response. Individual anemones were consistent in the duration of their startle responses, from slow to quick, among trials. An individual anemone taking 200 seconds to retract their tentacles in the first trial would, give or take a few seconds, take the same time in a second and third trial. Individual anemone behavior was also consistent despite variation of the environment around them, in this case water temperature.

However being too much of individual can be a bad thing. Schools of small fish and herds of hoofed grazers necessitate the lack of individual behavior for group good. Well, kind of. The culmination of individual behaviors can actually come together to form complex group behaviors and self organize. But these self-organized systems are thought to be sensitive to varying personalities among individuals. For example, individual variability in ant movement can reduce the colony’s foraging efficiency.

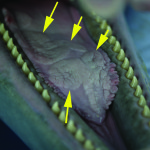

Among snails of the intertidal, desiccation is a major concern during times of low tide. One way to prevent desiccation is to seek shelter in a crevasse, among a group, or both [see the great photo here]. Or you could evolve into a subtidal snail but will ignore that route for now. But how do these snail collectives form? Do snails communicate with each other with complex clicking sounds that says we’ll be meeting at 2 clicks west at 0930 hours? Not likely. Groups form by chance but are regulated by three rules. 1. Snails move around randomly can choose to stop and aggregate when they encounter another snail. 2. Snails can choose to stop when they encounter a crevice. 3. They can follow mucus trails of other snails. Thus large aggregations are likely to occur at the intersections of mucus trails, crevices, or any point that slows the progress of a lead snail. All hail the snail leader!

During hot days you would expect snail behavior to change from cooler days. Like me when the temperature rises and the rock surface dries, snails spend less time moving. And even though larger aggregations are more advantageous on hotter days, aggregation are expected to be smaller because of the reduced time to congregate. This would obviously be sub-optimal self-organization. In simple computer simulations conducted by Richard Stafford and colleagues this is exactly what happens. Smaller aggregations occur on hotter days. Likewise, in simplistic experiments on flat marble slabs where snails are allowed to roam and aggregate freely, smaller aggregations occur on hotter days.

However, in the real world on hot days snails form clusters the same size as cold days. This appears in part because the surface complexity of rocks and various microhabitats afforded by crevasses, mitigates the changes in individual snail behaviors. Thus in the natural world, interactions among individuals occur on a backdrop of environmental complexity which produces self-organized systems insensitive to the individual behavior. In other words, the group good can prevail against individual personality as long as world is complicated.

Thus from snails and anemones we can take home a bit of wisdom. Be yourself and let your freak flag fly, because in our complicated world the good will prevail. Or maybe not.

Stafford, R., Williams, G., & Davies, M. (2011). Robustness of Self-Organised Systems to Changes in Behaviour: An Example from Real and Simulated Self-Organised Snail Aggregations PLoS ONE, 6 (7) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022743

Briffa, M., & Greenaway, J. (2011). High In Situ Repeatability of Behaviour Indicates Animal Personality in the Beadlet Anemone Actinia equina (Cnidaria) PLoS ONE, 6 (7) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021963

Good post, just the right level of detail for laypersons such as myself. I must confess, as a Midwesterner, that I envy your collective and easy access to the oceans.

Larry,

Thanks for the compliment. Glad you enjoyed the post!

Ahh I loved reading this post because I myself have a sea anenome that i’ve had as my pet for 3 years and from reading this I have concluded that my anenome is of the energetic sort, he/she is always moving around in the water and looking happy. Next time I get another anenome i’ll look for a more sensitive sheepish one.

Prof M

great post. Anemones are awesome – and there’s a wonderful image in my mind of these researchers having a lot of fun squirting water at the little anemones! (did they use tiny water pistols?)

It’d be really interesting to know if anyone has any ideas about what might explain these different response times… Does it come down to physical/physiological differences, say in nerve net development? Do age or previous living conditions have any effect?

My gosh! Who’da thunk those squishy stomachs with tentacles marched to their own drummers? Somebody HAS to try this with sponges. My gut (hehe) instinct is to guess that you need a nervous system–however primitive–to exhibit personality, but who knows? Wonder if anyone’s looked in single-celled critters? Thanks for the brain food!