If everything goes smoothly, this morning at around 11 o’clock, four brave souls strapped to 800,000 gallons of liquid oxygen, hydrogen and hydrazine will ride a controlled explosion into near-earth space aboard the NASA shuttle Atlantis. For the last time. The NASA space shuttle program is drawing to a close after 30 years, and Atlantis will be the last shuttle to launch from the Kennedy Space Center near Titusville Florida. I’m going to be there along with a million or so other folks keen to see at least one launch in their life. Having just been in Titusville last week for some dolphin health assessment research it was hard not to make at least a geographic connection to Atlantis (we could see the assembly building from where we were working), but when you learn more about that name, the connections between marine science and the shuttle program go much deeper.

If that name – Atlantis – were used in a survey on Family Feud, the mythical sunken city and the space shuttle would surely be the top two answers, with the Bahamian resort of the same name maybe in third. I wonder how many points people would get, however, if they answered “The first Woods Hole oceanographic vessel?” or “The vessel that discovered the wreck of the Titanic”? Not many, I’m willing to bet. That’s a shame, because the history of the name Atlantis in oceanographic research is significantly longer than the lifespan of shuttle Atlantis, or even the entire shuttle program, and at least equally auspicious scientifically. Indeed, Atlantis the shuttle is named after R/V Atlantis the WHOI vessel, the ketch-rigged ship that is enshrined in the logo of that much vaunted institution. On this momentous occasion of the final shuttle launch, it seems like a good time to look back at the achievements of research vessels named Atlantis and their roles in the history of oceanographic and space research.

The first R/V Atlantis

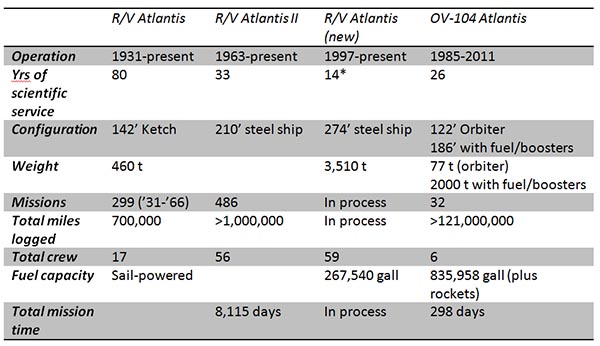

There have actually been three WHOI ships called Atlantis. The first and perhaps most famous was the first ship built in America that was dedicated to oceanographic research; it was launched in 1931 and carried out 299 research cruises for Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution over the next 35 years; operating in all oceans and discovering in 1947 the abyssal plains, those vast submarine flatlands that occupy much of the bottom of the open ocean. It was this 142 foot ketch-rigged ship (with an anaemic 280HP diesel backup) that was honored by the eponymous space shuttle. During it’s time at WHOI, R/V Atlantis logged over 700,000 miles, toting a crew of just 5 9 scientists all over the world., but Atlantis didn’t wind up in a junkyard or at the bottom of some stormy corner of the sea; it is still in service! It was sold to the Argentinian government and now serves as the R/V Dr. Bernardo A. Houssay, an oceanographic research and survey vessel. At 80 years of continuous operation, the original Atlantis far outlasted the shuttle that was named for it. Indeed, its operational history outspans the entire era of human space exploration.

Atlantis II

Atlantis II served WHOI for a similar period as the original Atlantis: 33 years, from 1963 to 1996. A more substantial diesel powered ship of over 200ft in length, it served as the home for the submersible Alvin for over ten years and it was on board this vessel that a team lead by Bob Ballard discovered the wreck of the infamous RMS Titanic (see comments below for a correction).

Atlantis (the third)

Atlantis II was replaced by the most recent R/V Atlantis, which launched in 1997 and still operates for WHOI today as a state of the art research vessel, with a range of over 17,000 miles and over 3,000 square feet of lab space that can support up to 24 scientists for as many as 60 days. The current expression of an oceanographic research vessel of this kind is probably about as far removed from the original Atlantis as the shuttle Atlantis is from the first man made orbiting device: Sputnik.

NASA kicked off its radical space shuttle program with the launch of the orbiter Columbia in 1981. The agency demonstrated its commitment to near-earth operations by building 6 similar orbiters: Enterprise (test-bed), Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour. OV-104 Atlantis made its debut in 1985, about half way through the operational life of the second WHOI ship Atlantis II. Among its greatest achievements were the deployment of the Magellan probe to Venus and the Galileo probe to Jupiter, both in 1989, as well as delivering the Destiny module (the main US research module) to the International Space Station. This final mission, STS-135, will be the 33rd for Atlantis, which will then live on as part of the exhibitry at the Kennedy Space Center (the other 3 extant orbiters will go to Smithsonian, New York and Los Angeles).

I am no expert on the legacy of R/V or OV Atlantis, so I asked the Executive Director of WHOI, Dr. Susan Avery, and she was kind enough to talk with me about the role of Atlantis in oceanographic and space research:

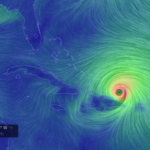

AD – Your personal research interest is in ocean-atmosphere interactions, can you compare the state of what we’ve learned about the oceans and atmosphere from oceanic research vessels like R/V Atlantis, Atlantis II and the new R/V Atlantis, with what we’ve learned from the sort of remote sensing tools deployed by shuttle Atlantis? One obviously has a much greater price tag than the other; has it been worth it?

SA – Satellite based observations of the ocean give us global coverage of key parameters such as sea surface temperature and winds and ocean productivity, but do not tell us anything about the ocean beneath the surface – our “inner space”. In order to gain knowledge about the ocean below the surface we need ships to help deploy instruments that provide observations of the physics, chemistry, and biology of the ocean as well as the seafloor. Our current understanding of the ocean is determined from observations from both satellite and ship platforms utilizing a variety of sensors. The challenges of getting platforms and sensors into the ocean rival – if not exceed – those of getting into space. The nature of the regions (space and ocean) being explored dictate the cost of exploration. The price of space exploration is dictated by distance to travel and the cost of lifting everything you need into orbit. The price of ocean exploration is dictated by the extreme pressures, corrosiveness, and communication and power challenges. The price tag is worth it for both types of platforms.

AD – It seems that one key to the success of the shuttle program was the development of a standard platform for orbital operations, but ocean exploration still seems to operate on a custom-built model, where tools like R/V Atlantis and the submersible Alvin and ROV Jason are developed as-needed. Do you think there’s benefit to the development of a standardized platform for deep sea research? Would that make submersibles/ROV’s more recognizable to the public?

SA – Modern ROVs and UAVs such as Jason, Nereus, Sentry, and the Remus vehicles can be launched from many different types of ships. Alvin and Atlantis are special cases – they are coupled. There is a benefit for standardizing platforms provided they can continue to support the latest sensor technologies. The Argo network provides a standardized set of floats that provide standardized observations of the upper ocean. Remus can be thought of as a standard platform that accommodates various sensors depending on the task to be done. With the Ocean Observatory Initiative now being constructed by the ocean science community, we will be putting standardized infrastructure in the ocean to take routine near-real time observations with the flexibility to be expanded to accommodate sensors and instruments by users across the ocean science community.

AD – Space research, even the sort of near-earth non-exploratory research made possible by shuttle Atlantis, has always seemed to grab the public’s attention more than ocean exploration, despite the fact that parts of the sea are far less understood and equally challenging to work in. For example, there are predictions that as many as a million people will attempt to see the Atlantis launch in person. Could and should the marine science community do more to sell ocean exploration to an increasingly cynical public? How might we do that?

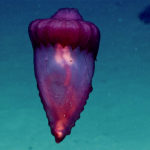

SA – You are right that “Outer” space has captured the imagination and interest of the public more than “Inner” space, in large measure due to the investment NASA has made into the tools to capture amazing imagery –critical to captivating public interest and continued support for NASA’s mission. The ocean science community has put less emphasis on imagery (in part because of the way ocean research is funded), but that may be changing. Increasingly, the community recognizes the value to research and to public outreach of equipping deep sea research vehicles with high-definition video cameras. The ocean has a great story to tell and its mystery does capture people’s attention – especially during specific events such as a whale beaching or finding a downed aircraft, or the Titanic, or even what was happening in the Gulf during Deepwater Horizon. Communicating to the public about the critical importance of the ocean to their lives and the need for exploration is important to do but not only involve the marine science community but also the media and communication experts.

In thinking about Dr. Avery’s comments, the power of drama and imagery is obvious. A rocket launch is clearly a much bigger and more dramatic event than a NOAA ship pulling out to sea or even a submersible being deployed off an A-frame, even though (as she points out) many of the challenges of oceanographic research are similar or even greater. But there’s more to it than that. NASA missions are named, their execution hyped, and their crews uniformed. It is branding at it’s best. That doesnt happen to the same degree in marine science. If we want marine science to attract the same amount of public support and enthusiasm as it did during the Cousteau years (branding again), perhaps it should. It’s not just about getting respect, because when it comes to the crunch, that public support translates to funding. These are tough issues that I look forward to thinking and maybe writing more about, just as soon as my ears stop ringing*.

*As of 11PM on 7/7/2011, the launch looked unlikely for 7/8 due to weather concerns. If it does eventually happen before Sunday, I’ll post pics from our spot at Kennedy Space Center.

Just a slight correction. Titanic was discovered during an expedition on another research vessel operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, the Knorr—not Atlantis II.

Thanks for setting me straight

Just to clarify, Ballard was aboard the Knorr when they discovered the wreck by sonar in 1985, but it was from Atlantis II that the team first saw the wreck a year later, onboard the submersible Alvin

You clarification is not accurate. Titanic was discovered and first photographed by the deep-towed sonar and video camera system Argo, developed by the Institution’s Deep Submergence Laboratory (DSL),and deployed from Knorr on the 1985 voyage. Additional 35-mm photographs were taken by ANGUS (Acoustically Navigated Geological Underwater Survey), another towed vehicle developed at the Institution. WHOI scientists returned to the Titanic in 1986 with Atlantis II, Alvin, and the remotely operated vehicle Jason Jr.

Some more details for those interested: The discovery of Titanic was a joint French-American effort begun earlier in the summer of 1985 with a cruise aboard the French research vessel Le Suroit to test France’s new sonar system, SAR (System Acoustique Remorquè). Dr. Robert D. Ballard, leader of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Deep Submergence Laboratory and another WHOI colleague, participated in that cruise, which ended in early August. Three scientists from Institut Français De Recherche Pour L’Exploitation de la Mer (IFREMER) joined the American cruise aboard Woods Hole’s Knorr August 15 in Ponta Delgada, Azores, for the trip across the Atlantic to the vessel’s home port at Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

Using sonar imagery in the hunt for Titanic, the earlier French cruise had ruled out large sections in a 150-square-mile search area, allowing the Knorr cruise to concentrate on the remaining areas under a different search strategy. The first visual contact of Titanic was made about 230 miles south of Nova Scotia. Debris including one of the ship’s boilers and was made by Argo just after 1:00 a.m. EST September 1, 1985. The seven-member scientific watch that saw the first images included four Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution personnel, two French scientists, and a U.S. Navy officer and was led by Jean-Louis Michel (IFREMER), co-chief scientist with Dr. Ballard of the expedition. Video filming from Argo and 35-mm filming from ANGUS were conducted throughout the remaining four days of the voyage.

Thanks for your detailed clarification

The original ketch, R/V Atlantis was not built in America. Shae was constructed at the Burmeister & Wain yard in Copenhagen,Denmark. Columbus Iselin was the ship’s master when she was delivered from Denmark to Woods Hole.

I have deleted the word “built” from the relevant sentence

Actually, reading your reply again, I believe my clarification IS accurate – the team saw the wreck from the Alvin, deployed from Atlantis II in 1986, did they not? If I read your response correctly, everything prior to that was either sonar or photographs.

I appreciate the attention to detail of the folks commenting from Woods Hole but I can’t help feeling that maybe you’re missing the point I’m trying to make to a readership much less familiar with the finer details of WHOI history than you (and I freely admitted in the original post that I am not an expert on that subject). My point is that cool stuff was being done by vessels called Atlantis – YOUR vessels – long before the space shuttle of the same name came along.

Points well made, both in the above comment and in your fist post on the subject. The parallel of the spirits of exploration behind RV Atlantis and OV Atlantis was clear, and my niggling detail unnecessary. As I’m sure your aware, the same sort of parallels exist between the names of all the orbiters and sea-going vessels of exploration.