James Cameron’s Aliens (1986) is the greatest movie ever made. There, I said it. For sheer script quotability, only Pulp Fiction comes close. For dark and gritty, anti-glossy-Star-Wars sci fi realism, only Blade Runner is its equal. And no critter has ever been more terrifying than the H.R. Giger creation that debuted as a solitary shadow-dwelling nightmare in the original Ridley Scott suspense masterpiece Alien (1979), and returned in the sequel as a bloodcurdling horde to kick some serious space marine arse right out in the open (The third one is just OK, but don’t mention Alien Resurrection, I don’t want to talk about it…).

James Cameron’s Aliens (1986) is the greatest movie ever made. There, I said it. For sheer script quotability, only Pulp Fiction comes close. For dark and gritty, anti-glossy-Star-Wars sci fi realism, only Blade Runner is its equal. And no critter has ever been more terrifying than the H.R. Giger creation that debuted as a solitary shadow-dwelling nightmare in the original Ridley Scott suspense masterpiece Alien (1979), and returned in the sequel as a bloodcurdling horde to kick some serious space marine arse right out in the open (The third one is just OK, but don’t mention Alien Resurrection, I don’t want to talk about it…).

Among it’s tooth dripping, teeny-2nd-jaw-snapping horror, though, Aliens also has some pretty cool biology going on, especially with respect to life cycles. There are many parallels between the Alien’s abhorrent life history on planet LV426 and the way many parasitic organisms live here on earth. Indeed, there are a lot of crazier and more disturbing life cycles that are real and out there, happening every day, on THIS planet. Let me show you what I mean.

The Face Hugger. Much of the first Alien film centered on the Nostromo crew’s experiences with a peculiar spider like creature that hatches from a 2-foot tall egg and attaches itself to John Hurt’s face while they’re exploring a putative distress beacon from planet LV426. This creepy headless critter, with its arachnid movements and constrictor-like tail, played on the worst primal human phobias of spiders and snakes at the same time. Add to that its singular determination to envelop the face of its victims in a vice-like embrace and you truly have the stuff of nightmares. After a while though, the critter drops off, seemingly by itself, and dies. Everything goes back to normal until some time later when John Hurt lurches onto a breakfast table and one of the most memorable horror scenes ever unfolds as the alien monster – in its more traditional jaw-snapping form – bursts out of his chest (we’ll come back to that).

The Face Hugger. Much of the first Alien film centered on the Nostromo crew’s experiences with a peculiar spider like creature that hatches from a 2-foot tall egg and attaches itself to John Hurt’s face while they’re exploring a putative distress beacon from planet LV426. This creepy headless critter, with its arachnid movements and constrictor-like tail, played on the worst primal human phobias of spiders and snakes at the same time. Add to that its singular determination to envelop the face of its victims in a vice-like embrace and you truly have the stuff of nightmares. After a while though, the critter drops off, seemingly by itself, and dies. Everything goes back to normal until some time later when John Hurt lurches onto a breakfast table and one of the most memorable horror scenes ever unfolds as the alien monster – in its more traditional jaw-snapping form – bursts out of his chest (we’ll come back to that).

This life history follows the general form egg hatches –> animal develops –> animal lays embryo in host and dies –> host is killed by emerging embryo. This is a life history used by thousands of species here on earth and is what parasitologists (those who study parasites) and entomologists (those who study insects) would call “parasitoid”. Parasites are animals that are smaller than their hosts and live at their expense, deriving shelter and nutrition from the larger host animal. A parasitoid is a special type of parasite where there is close to a one-to-one ratio of parasitoids to hosts (one face hugger to one John Hurt) and where the parasitoid invariably kills the host (putting the rest of us off eating breakfast for a while). By contrast, many parasites can occur in large numbers on a single host and they generally don’t kill them – its not in their best interests to do so. The parasitoid life style has evolved in several different groups but is best known among wasps, where thousands of species make a living laying their eggs on other insects, in which they hatch and then eat the hapless victim out from the inside. If this is all sounding vaguely familiar it may be because you may have read about this before: Carl Zimmer describes it in his excellent book Parasite Rex.

This life history follows the general form egg hatches –> animal develops –> animal lays embryo in host and dies –> host is killed by emerging embryo. This is a life history used by thousands of species here on earth and is what parasitologists (those who study parasites) and entomologists (those who study insects) would call “parasitoid”. Parasites are animals that are smaller than their hosts and live at their expense, deriving shelter and nutrition from the larger host animal. A parasitoid is a special type of parasite where there is close to a one-to-one ratio of parasitoids to hosts (one face hugger to one John Hurt) and where the parasitoid invariably kills the host (putting the rest of us off eating breakfast for a while). By contrast, many parasites can occur in large numbers on a single host and they generally don’t kill them – its not in their best interests to do so. The parasitoid life style has evolved in several different groups but is best known among wasps, where thousands of species make a living laying their eggs on other insects, in which they hatch and then eat the hapless victim out from the inside. If this is all sounding vaguely familiar it may be because you may have read about this before: Carl Zimmer describes it in his excellent book Parasite Rex.

Alternating Generations. The face hugger is all well and good and scary and creepy and stuff, but there’s another bit of biology going on here too. On the breakfast table, the creature that bursts from John Hurt’s chest (causing Veronica Cartwright to pass out during filming when she gets a face full of blood – true story!), is not the same type as the one that grabbed his face in the first place. If you think about it, the human life cycle goes egg –> juvenile –> adult (mating) –> egg, but in the Alien’s case it goes egg –> face hugger (implantation) –> embryo –> juvenile –> adult (mating) –> egg. In other words, there are two larval stages, egg and stomach embryo, giving rise to two “adult” stages, Face hugger and Mr Two-sets-of-jaws, thus two alternating generations. As, ahem, alien as this life cycle is to us, there are actually thousands of species here on earth that do follow this alternating generations model; the best examples are among the parasitic flatworm group called the Digenea or “trematodes” or “flukes”.

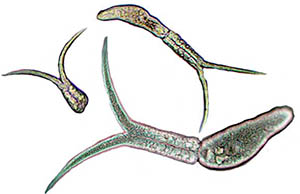

In these marvelous little parasites, of which there may be 60,000 species or more infecting all classes of vertebrates and many invertebrates, alternating generations are universal. It generally goes like this: Egg –> Larva 1 (miracidium/mother sporocyst) –> Larva 2 (daughter sporocyst/redia) –> Juvenile (cercaria/metacercaria) –> Adult –>Egg. You can see that in this case there are actually three generations: Larva 1: Miracidium+Mother sporocyst, which hatches from egg and gives rise asexually to Larva 2: Daughter sporocyst or redia which gives rise asexually to the Juvenile/Adult which then lays eggs, completing the life cycle. Larva 1 and Larva 2 generations both live in molluscs, which were the original evolutionary host for this group. Juvenile/adult generation occurs in a wide range of invertebrates as juveniles, and typically in vertebrates as adults. What’s with all the generations? Well, it’s all about reproduction. By reproducing through two generations asexually within the mollusc host, the reproductive potential of a single egg is multiplied exponentially to produce, potentially, thousands of adults. Those adults lay thousands of eggs, so you can probably guess that digeneans have phenomenal fecundity. They need it because, like turtle hatchlings braving the open ocean, only a handful of parasites will survive every life cycle step and reach adulthood.

It gets better though, because this general model has been modified an untold number of ways in different groups of digeneans. Here’s how some researchers at Cambridge tried to encapsulate those variations:

You can see that this is very involved, with any number of possible pathways that the life cycle of any given species could follow. By comparison, the Alien life cycle is actually pretty straightforward! A lot of that diversity in life histories has probably resulted from the diversity of hosts and diversity of ecological relationships (especially who eats whom) in the oceans. That’s because the mollusc first hosts are primarily aquatic and ridonkulously diverse (>80,000 known species), and the greatest diversity of digeneans is focused among the fishes, of which there are perhaps 30,000 species. Those of you mathematically-inclined can start to estimate how many possible combinations that is, especially if you layer in the other (juvenile) stage (“2nd intermediate host” in the diagram above), which can occur in pretty much anything.

What of the chest burst, does that have an equivalent in nature? You betcha. On the diagram above, that arrow from the “1st Intermediate host” box to “cercaria” means burrowing out through the flesh of the mollusc to the outside, a task that’s achieved by secretion of all sorts of nasty enzymes, plus a bunch of wriggling. In some senses it’s not as dramatic as the chest burst (these parasites are, after all typically <1mm in size) but in other ways more so, as it’s not usually one that’s coming out, but thousands. You can imagine that this is not good for the mollusc. What the hell, they’ve been sterilised anyway. Oh, I didn’t mention that these parasites castrate their mollusc hosts? Cos that’s kind of important, especially for the mollusc…

One important difference between what Giger’s Alien does and what nature does is that, despite the alternating generations, the Alien life cycle is still what parasitologists would call “simple”. In this context “simple” means “involving only one host to get from egg to egg”. By contrast, “complex” means “involving multiple compulsory hosts to get from egg to egg”. Simple/complex is one of those situations where scientists in one particular field have a modified and specific meaning for a word in common usage. Thus the Alien life cycle is simple, despite appearing complex. Clear as mud, right? Another important difference is that only one of the Alien generations is parasitic. The Face Hugger is a parasitoid, but the adult Alien adult is a predator (as the marines discover only too quickly!). In the Digenea, all generations are parasitic at some point. They are rarely predatory, except for some redia larvae, which can actively prey on other parasites that invade the same mollusc host (but that’s a whole ‘nother blog post).

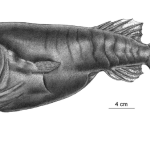

The Aliens might have one sinewy, taloned leg up on digeneans when it comes to being social. The adult Aliens display classic social behaviour like ants, bees or naked mole rats. There’s a queen Alien tended by soldiers and drones, and the queen is the only one who gets to lay eggs. This is not typically the case for digeneans, BUT, they do occasionally diversify roles, and perhaps they are socially organised and we just haven’t realised yet. Consider Hirudinella, a huge digenean that lives in the stomach of wahoo fish, Acanthocybium solandri; it’s usually found as a pair of mature worms, with occasional juvenile hangers on. How does this come about? How do the two adults prevent the maturation of other worms that colonise the fish’s stomach? No-one really knows.

The digenean life cycle is really a marvel of nature and proof positive that real life (in the biological sense) is often more diverse, startling and amazing than humans can imagine and portray in moving pictures. Some have even looked at the complexity of digenean life cycles as evidence of intelligent design (pffthtt!). If only they had acidic blood or could throw out snappy lines like “They mostly come at night, mostly” or “We’re in some pretty shit now, game over man, GAME OVER!“, perhaps digeneans might one day garner a little more respect in the pop-culture milieu. In the meantime, Netflix yourself the extended version of Aliens (the one with the bad-arse robot sentry guns!), make yourself some kettle corn, and impress your friends with tales of parasitoids and the alternation of generations.

I’m a massive fan of the Alien series, and had an excuse to use a screencap of the chestburster from Alien in a journal club presentation. It was about this paper, seriously freaky in its own right: apparently a virus which helps kill the caterpillar so the wasp larva can eat it, doesn’t have its own structural protein genes in the viral genome. Apparently at some point they wound up in the WASP genome. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/323/5916/926.abstract

Now I am tempted to pick up one of these:

http://www.thinkgeek.com/geektoys/plush/c534/

WANT!

Another cool example that fits with this theme: the moray eel has a second set of ballistic jaws in its throat: http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/notrocketscience/2009/08/10/moray-eels-attack-with-second-pair-of-alien-style-jaws/

What a fun way to learn about parasitoid’s!

Excellent Work Dr. Dove!!!!!!!!!!

Ed, that is SO awesome. I’ve known about pharyngeal teeth for ages, but I had no idea they were protrusible in morays. Fantastic stuff!

Wow, you _really_ need a map to navigate that life cycle!

The Movie That Won’t Be Mentioned is my favorite though. (What? It’s bad biology, but the physics stinks in all of them, and the story and acting is mostly great.)

Sheer quotability? Duuude, you’re being very undude. What about The Big Lebowski??