Dr. M’s article in Wired truly stirred something in me this morning.

We need to put names on things.

I’m a scientist who has always strived to be integrative—I believe you need to understand all sides of a debate in order to fix the root of the problem. I’ve tried everything from traditional nematode taxonomy, high-throughput molecular phylogeny, and in-situ hybridization in zebrafish (in my undergrad/Ph.D. era), to nematode genomics, 454 sequencing of whole sediment communities, and transcriptomics in my current postdoc. I’m also learning computer programming. (Apologies to Carl Zimmer for breaking all the rules in one paragraph. To my non-scientists, for whom that was all jargon: I have been trained to do research in a LOT of different things).

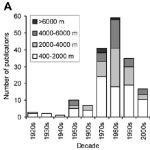

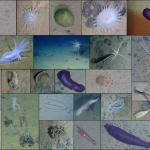

Compared to the other research I’ve done, nematode taxonomy is hard, back-breaking labor. You can only look at so many worms per day, and your eyes can only withstand so much beating. Trust me. But in spite of these drawbacks, the only reason we know anything about deep-sea nematodes (and countless other ‘minor’ phyla) is because of diligent, dedicated taxonomists.

We can’t even do genetics without taxonomy. My current projects use high-throughput gene sequencing to look at communities of microscopic marine animals living on the seafloor (generating millions of DNA barcodes for many of the neglected phyla that Dr. M mentioned in the article). We have to match up our DNA sequences with online genetic databases—where someone, somewhere has looked at an individual nematode, tardigrade, or kinorhynch, said “ah, yes, this anatomy means it is Species X” and has then gone on to get a gene sequence for that same animal. Without a close relative in the database, our DNA sequence from species X will be labelled as having “no match” , and species X will continue to be a name-less, phylum-less enigma.

Yet, taxonomy is an old institution and can be resistant to change. We know far too much about genetics to deny the utility (and objectivity) of DNA sequences in biodiversity research. Why aren’t we training integrative taxonomists, who understand morphology but are also adept at sequencing genes? Why, instead of pushing hard to revolutionize and modernize a powerful field, are scientists watching it die?

Science needs to put names on things—not just because we as humans want to organize life, but because it is critically practical.

In the wake of heartbreaking environmental disasters, public outrage is inevitable. Companies can get away with murder (the deaths of nameless, undiscovered animals), and wipe their hands clean after paying shockingly lenient fines.

Determining reparations for the Gulf oil spill will be a regulatory process, not an emotional one. The Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) process requires a detailed iteration of “damage to ecosystem services” and puts a cost on these perceived damages. In this case, ignorance really IS bliss (for BP, anyway); in the absence of baseline biological information, the default assumption is that no damage has been done. If we never knew species were there, we’ll never know that they disappeared.

I believe it is possible to do both high-impact science AND taxonomy within a single project. With the rapid advance of DNA sequencing technologies, investigating the biodiversity of small, diverse animals is cheaper, faster and more feasible than ever; taxonomy is (and should be) a required complement to these studies. Integrating historically disparate scientific disciplines will require much resolve, collaboration and enthusiasm amongst scientists.

We are indeed in a biodiversity crisis, but I am ever the optimist.

thank you for this article. this is exactly the kind of commentary i (as a lay person) hope to find when i come here. i appreciate the time you took to write this and express your insight to the topic and explain more deeply why it’s important. i’m sure you could have been doing a million other things rather than write a blog post today, so thank you.

We heart our readers <3 :)

I stumbled onto this from another post, but I’ll do a +1 on JRIllinois.

But it got me thinking: “If we never knew species were there, we’ll never know that they disappeared.” What if in genomics term we could observe diversity? (I dunno if it is possible, however.) And what if genetic diversity takes a hit as species (or simply enough individuals, perhaps) disappear?

In that case the argument wouldn’t go through as I understand it. Surely there are other cases for taxonomy, but this may not be one of them.