I wrote a piece on the plight of our favorite “winged” mollusc, the pteropod, in arctic seas over at Scientific American’s guest blog.

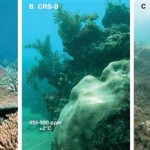

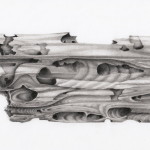

[…] To grasp how our input of CO2 feeds back upon polar foods webs we can use the unassuming pteropod mollusk, commonly called the sea angel because of its modified wing-like (ptero-) foot (-pod), as a case study. Pteropod mollusks are particularly susceptible to ocean acidification because their carbonate shells are very thin and composed of aragonite, which is 50% more soluble in seawater than calcite, the other form of calcium carbonate. Hence, they are considered a “canary” in the climate change coal mine. Orr and colleagues (2005) examined the fate of the pteropod’s fragile shell under “business as usual” CO2 emissions. After 48 hours, shells edges were already acid-pitted (Orr et al. 2005). Calcification is a physiological process and organisms exert some degree of control over the enzymatic constituents, but it is an energetically expensive process (reviewed in Fabry et al. 2008). When shells get damaged, animals must exert even more precious energy to repair the damage. […]

Read the whole article over at Scientific American! (set in the context of the Lorax)

Share the post "To Catch a Fallen Sea Angel: How a Mighty Mollusc Detects Ocean Acidification"