John Hocevar is a marine biologist and is the Oceans Campaign Director for Greenpeace USA, where he oversees their oceans and fisheries work, including efforts to get major supermarket chains to improve the sustainability of their seafood, to establish a network of large scale marine reserves, to protect the Arctic Ocean from offshore drilling, and to end commercial whaling. He learned to pilot a submarine so he could explore the largest underwater canyons in the world, in the Bering Sea, which for the moment remain vulnerable to industrial fishing.

John Hocevar is a marine biologist and is the Oceans Campaign Director for Greenpeace USA, where he oversees their oceans and fisheries work, including efforts to get major supermarket chains to improve the sustainability of their seafood, to establish a network of large scale marine reserves, to protect the Arctic Ocean from offshore drilling, and to end commercial whaling. He learned to pilot a submarine so he could explore the largest underwater canyons in the world, in the Bering Sea, which for the moment remain vulnerable to industrial fishing.

——————————————————————————————–

More than six months after the BP Horizon rig exploded and sank into the waters of Mississippi Canyon, we still have very little understanding of what the impacts will be to deep sea marine life. As Dr. Bik pointed out, NSF spent just $250,000 on benthic communities out of the $19.4 million Rapid Response grants awarded thus far. While some important work has been carried out with BP funding, there is no denying that the company responsible for this disaster has sought to use its primary funder status to influence the direction of research – and even, in some cases, how and when results are communicated. These facts, combined with the “mission accomplished/nothing to see here” tone of many government statements on the spill, led Greenpeace to decide there was a need for more independent research to assess the scope and impacts of the BP Horizon disaster.

More than six months after the BP Horizon rig exploded and sank into the waters of Mississippi Canyon, we still have very little understanding of what the impacts will be to deep sea marine life. As Dr. Bik pointed out, NSF spent just $250,000 on benthic communities out of the $19.4 million Rapid Response grants awarded thus far. While some important work has been carried out with BP funding, there is no denying that the company responsible for this disaster has sought to use its primary funder status to influence the direction of research – and even, in some cases, how and when results are communicated. These facts, combined with the “mission accomplished/nothing to see here” tone of many government statements on the spill, led Greenpeace to decide there was a need for more independent research to assess the scope and impacts of the BP Horizon disaster.

We started in Florida, looking at sponges with Charles Messing and Joe Lopez from Nova Southeastern University. Because sponges filter large quantities of water, they are a good place to look for impacts of even low concentrations of oil or dispersant, in the form of changes to microbial symbionts. It’ll take six months before the analysis is completed, a good reminder that science is slow, and policy makers should not be too quick to assume they understand much about what the full damage toll will be.

Caz Taylor and Erin Grey of Tulane University have been doing some important work with blue crab larvae, so we were happy to make the ship available to them to conduct several days of plankton tows. That analysis will take quite a while to complete, but they are growing increasingly concerned about the mysterious orange blobs turning up in their samples. If the blobs turn out to be oil or dispersant, this will be bad news for more than the blue crabs, as it will show one way that these contaminants are entering the food chain.

We helped a team from the Littoral Acoustic Demonstration Center deploy and retrieve acoustic monitoring buoys, which recorded phonations of sperm and beaked whales. The team has strong baseline data from multiple years, so this study should help us understand what the BP disaster has done to Gulf whale populations. According to NOAA scientists, losing as few as three adult sperm whales could be enough to lead to the demise of the entire population in the Gulf, so we are anxious to see the results. Natalia Sidorovskaia hopes to have preliminary findings ready to present later this month.

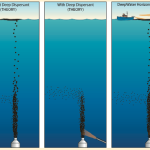

But what about the deep sea? Well, if sperm whales don’t count for you, the last two projects might. Rainer Amon and Clifton Nunnally of Texas A&M looked at oil in the water column and sediments. Using a CTD, dissolved oxygen meter, and a flourometer to detect anomalies, we collected water samples from 300 miles to the west of the spill origin that appear to be part of a subsurface plume. One of the sediment samples taken from about 1400 meters contained oil that we were able to confirm originated from the Deepwater Horizon site. Further analysis will be needed to better understand the scope of the plume and the impacts on benthic invertebrates collected in the box core samples.

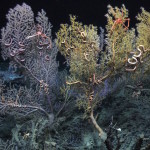

Finally, we used a Dual Deep Worker two-person submersible to look at impacts to deep sea corals with Steve Ross of UNC and Sandra Brooke of the Marine Conservation Biology Institute. The good news here was that we saw no visible signs of oil near the corals, which appeared to be healthy. Of course, it will take further analysis to see if there are sub-lethal effects, such as reduced growth rate or reproductive success, or if the corals are more susceptible to disease.

Of course, all of this work still doesn’t scratch the surface when it comes to fully understanding what the impacts of the BP Horizon disaster will be, which will be felt for decades. We were pleased to be able to contribute to the work being done in the Gulf, though, and will work with our scientific partners to ensure the results are shared with the public and with policy makers.

First rate reportage guys, this is my mind breakfast for the day, mmmmm delicious.

John–Thanks for the wonderful post (including shout-out), and thanks for highlighting the hard work of all the fellow scientists working on projects in the Gulf. Clifton Nunnaly has kindly donated some samples from the Greenpeace cruise, and these are the first post-spill deep-sea samples we were able to get our hands on. Yes, despite all the subsurface monitoring and sample collection by NOAA and BP, it was the scientists who came through for us. Can’t wait to pyrosequence the meiofaunal communities in these cores!!

Nice work, John. Greenpeace is clearly helping to fill a communication and research gap in the Gulf of Mexico. Please, keep up the good work.