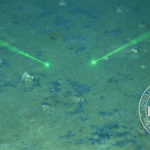

Enter the sieve. It is a marine biologists best friend, saving hours of sorting and enabling quantification of fauna. In fact you can get these miracle workers at McMaster-Carr for a mere $40-50. You take good care of these puppies and they will last several graduate student’s lifetimes! I prefer the 500 micron mesh size myself, but usually on top of the 64. You see, those damn limpets (Scheißeschnecke!!) always foul things up. I mean, there are ALOT of little limpets in vent ecosystems. Govenar et al. 2002 found up to nearly 100,000 of these bastards per square meter in tubeworm clumps at the Juan de Fuca Ridge. Sorting tens of thousands of limpets can be quite drearisome and on the occasion you find something that is to be classified as no a limpet is a moment of silent (or not so silent) joy. Stacking different size sieves has been a strategy that I have partaken in extensively in my career of bean counting.

![]() The sieve size I use at the bottom though is the most important. It is my cut off. I am essentially saying I will ignore anything which exists that can fall through this size hole. Though I would ideally like to have this be as low as possible, usually around 64 micron – the cutoff size for meiofauna, I am often limited by what size my colleagues have used in past studies. This is important because my results need to be compared to theirs if I want to understand general patterns in species compositions and community structure. But a new study, building upon a slightly older one, reminds us that instead, interpretations might be limited by sieve size.

The sieve size I use at the bottom though is the most important. It is my cut off. I am essentially saying I will ignore anything which exists that can fall through this size hole. Though I would ideally like to have this be as low as possible, usually around 64 micron – the cutoff size for meiofauna, I am often limited by what size my colleagues have used in past studies. This is important because my results need to be compared to theirs if I want to understand general patterns in species compositions and community structure. But a new study, building upon a slightly older one, reminds us that instead, interpretations might be limited by sieve size.

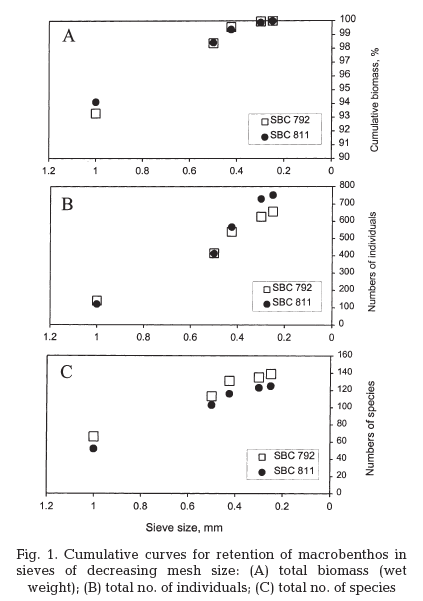

Gage and colleagues published an important methodological paper in 2002 describing the influence of sieve size on characterizing a deep sea community. The graph to the left is from their paper and clearly shows the biomass, numbers of individuals and numbers of species significantly increasing for 2 independent box-core samples. About 20 more species were recovered by winnowing down from 500 micron to 250 micron mesh. Twenty species is no laughing matter. That can mean the difference between a significant treatment effect or “meh, nothing here”.

Gage and colleagues published an important methodological paper in 2002 describing the influence of sieve size on characterizing a deep sea community. The graph to the left is from their paper and clearly shows the biomass, numbers of individuals and numbers of species significantly increasing for 2 independent box-core samples. About 20 more species were recovered by winnowing down from 500 micron to 250 micron mesh. Twenty species is no laughing matter. That can mean the difference between a significant treatment effect or “meh, nothing here”.

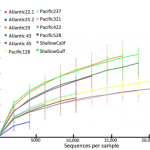

In a recent paper published in Marine Biology Research, Pavithran and colleagues took it a step further and asked if it mattered what type of animal was being shaken down the gauntlet. Using a replicated transect of box-cores in the Indian Ocean they looked at the effect a 200 micron difference in mesh size (between 500 and 300 microns) had in characterizing 7 very different animal groups: nematodes, polychaete worms, tanaids, a type of copepods, isopods, bivalves and nemertines (a worm-like animal).

The authors found the greatest difference in biomass occurred with the polychaetes, up to 90% reduction using the 500 micron mesh, followed by 78% reduction of nematode biomass. But a reduction in biomass doesn’t necessarily translate to a reduction in species present on the larger mesh size. After all, it could be smaller individuals of one or two major species retained on the smaller mesh. Unfortunately in this case it did translate, quick significantly too. The smaller mesh retained 66 species, while the larger mesh only 40. Additionally, there were nearly twice as many individuals on the smaller mesh sieve. This actually translates to a loss of 43% of the species, just from simple methodology choices alone!

What does this mean for interpretation though? As I mentioned above, one of the important things in designing a study is make sure your work will be comparable to the work of others. But if other researchers have been missing a certain size fraction of the animal community, should you ignore it too? Meiobenthologists would respond sharply with a very vocal NO! In fact, they would argue that the majority of deep-sea studies are just plain wrong and misleading at best since traditionally, they have ignored a potentially important component of the deep-sea benthos. Some of the world’s best nutrient recyclers are in that under 200 micron size class. So perhaps interpretations are in general limited, especially if you want to make grandiose claims about general principles or ecosystem functioning. But the data gleaned is still important nonetheless. My concern is that there is likely a size class of deep sea animals between 64 and 250 microns that have remained undiscovered in the several decades of experimental deep-sea ecology because we didn’t sieve down enough! Potentially 40-50% of deep sea macrofauna could have been thrown overboard during the last 50 years!

Gage, J., Hughes, D., & Gonzalez Vecino, J. (2002). Sieve size influence in estimating biomass, abundance and diversity in samples of deep-sea macrobenthos Marine Ecology Progress Series, 225, 97-107 DOI: 10.3354/meps225097

Breea Govenar, Derk C. Bergquist, Istvan A. Urcyuo, James T. Eckner, & Charles R. Fisher (2002). Three Ridgeia piscesae assemblages from a single Juan de Fuca sulphide edifice: structurally different and functionally similar Cahiers Biologie Marine , 43, 247-252

Pavithran, S., Ingole, B., Nanajkar, M., & Goltekar, R. (2009). Importance of sieve size in deep-sea macrobenthic studies Marine Biology Research, 5 (4), 391-398 DOI: 10.1080/17451000802441285

Ahh sieving – brings back fond memories during my Masters of being out on the water, in the rain, washing mudgrab samples through a big stack of sieves. Followed of course by the love smell of formaldehyde!

You can usually gather about 20 to 60 species of deep-sea ostracodes, and around 30 species of foraminifers (excluding planktonics) with a mesh size between 64 to 250 microns.

Meiofauna or macrofauna?

Langerus heftii