“There is absolutely nothing to restrict the geographical ranges of animals in the deep sea. Dr. Wallich, the pioneer of deep-sea research, eighteen years ago recognized the deep homothermal sea “As the great highway for animal migration, extending pole to pole” Below 500 fathoms it is everywhere dark and cold, and there are no ridges that rise on the ocean bottom to within 500 fathoms of the surface, so as to bar the migration of animals in the course of generations from one ocean to another, or all over the bottom of any one of the oceans.” –Mosely 1880, p. 546

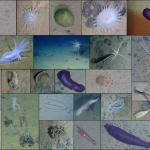

In the last 130 years, our view of the deep oceans radically changed. No longer is the largest environment on earth considered a dark homogenous wasteland, unchanging through time, buffered against climatic fluctuation, and devoid of biodiversity. The modern view of the deep-sea realizes a varied landscape comprised of reducing habitats such hydrothermal vents, methane seeps; mid-oceanic ridge systems and geologic hotspots that produce topographic complexity and new volcanic substrates; large food falls in the form of wood and whales that provide oases of food in a low productivity system; intricate canyon and slope systems presenting radical environmental shifts; and oxygen minimum zones intercepting continental margins. Even the expansive mud bottom that serves as the backdrop for these multiple habitats is considered a spatially and temporally dynamic system characterized by episodic benthic storms, internal tides, downslope debris and sediment flows, patchy carbon input across multiple scales, rich with biogenic disturbance and structure, and intrinsically linked to ocean surface processes. The hypothesis of a biological desert is but a ghost of science past put to rest by findings of spectacularly high biodiversity. But what of the notion of deep-sea species unbound by dispersal barriers able to distribute across to the farthest extents of ocean basins? What is the biogeography of the deep sea?

In a multipart series I will examine the biogeography (defined very well by Jim Lemiere as the patterns of the geographic distribution of biodiversity – where organisms are, where they ain’t, and who lives with or without whom) of the deep. I do this in conjunction with an invited review on the same project, authored by myself and two accomplished deep-sea biologists that I have longed admired and possess a deep respect for. My plan is to use DSN as sounding board for this project.

Now, the biogeography of deep-sea organisms is historically a black box characterized more by conjecture than data. Unsurprising given the remoteness of this environment and challenges to sampling it presents. Previously, many assumed, due to the lack of perceived environmental variability and geographic barriers, ranges of deep-sea species on the abyssal plains and continental margins were exceedingly large. New research utilizing higher-resolution sampling, molecular methods, and a ever-expanding amount of information in public databases are once again raising the question of how small marine invertebrates disperse across the vast distances of the ocean floor. Recent findings on unique seamount and chemosynthetic habits suggest high levels of endemism and challenge the broad applicability of single paradigm for all deep-sea environments.

Stay tuned for the first segment on the origins of deep-sea fauna.

Like! Sounds great.

I just love reading your news.