Post by Shawn M. Arellano. Dr. Shawn Arellano is a postdoctoral researcher at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Her PhD research at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology concerned the reproduction and recruitment dynamics of a methane-fueled seep mussel.

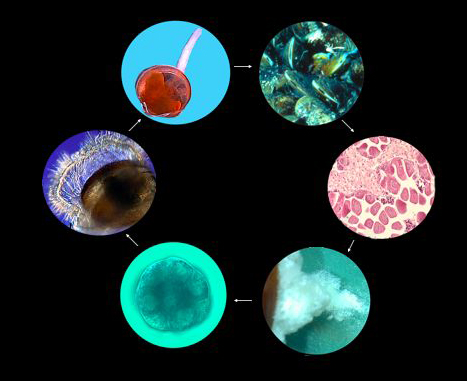

I have a dirty secret: I am a mussel sex voyeur. I’ve spent much of this century spying on mussels and hoping–nay, praying!–that they would squirt their gametes into the seawater. Don’t judge me yet; I am not really as twisted as I may sound. You see, I spent my graduate years studying “sex under pressure”. My focus,though, has not been on the sex act itself, but on the products of invertebrate love; specifically, the babies of the mussel Bathymodiolus childressi, a fabulous chemosynthetic mussel living at the cold-seeps in the Gulf of Mexico, including the famous Brine Pool (insert David Attenborough voiceover here: “An underwater lake!”).

To study the larval biology of any animal it is almost essential to develop laboratory culturing techniques, a major stumbling block when it comes to studying baby invertebrates from the deep. Although the first bathyal echinoid larvae were reared by Henri Prouho at the end of the 19th century (1,2), I know of only one complete developmental sequence for a deep-sea invertebrate (3). From deep-sea, chemosynthetic environments, larvae have been reared from only a handful of inverts, including several vestimentiferans, the “iceworm”, bone-eating worms, vent barnacles, cold-seep snails, and of course, my favorite, B. childressi. Why haven’t we reared the larvae of more deep-sea inverts? Here is a run-down of some obstacles:

1) Pressure. Although I say we study sex under pressure, the truth is that for most of the deep-sea inverts we have tried to culture, the sex part doesn’t actually require pressure. The mussels I studied required the same things some of you may like to get in the mood–a good meal and an intoxicant (No, not oysters and red wine. B. childressi prefer methane and a shot of serotonin). In fact, a common way to induce spawning in invertebrates is to stress them out–a quick trip from the depths of the ocean to the deck of a ship may just do the trick. The real challenge is fostering the development of the little embryos produced by these deep-dwelling lovers; many deep-sea embryos, especially from abyssal depths, require pressurization to normally develop. But, at what stage pressurization is necessary or whether pressure needs to change through development, for example, remain unclear and may vary between species or habitat depths.

2) Temperature? It has been suggested that vent inverts may delay development until they encounter high temperatures (4). Perhaps larvae migrating vertically from the deep-sea also need a temperature change through development?

3) Gametogenic seasonality. Yes, seasonality does exist in the deep sea. This may not seem like a big problem, but in practice ship schedules and the seasonal cycles of deep-sea animals do not always line up. Plus, a December spawning season sure can ruin your Christmas break!

4) What the heck do they eat? Seriously, if you know what I should be feeding my deep-sea invertebrate babies, email me.

5) What induces metamorphosis and settlement? Inducing metamorphosis and settlement can be difficult for cultured larvae of even shallow-water inverts. Honestly, most deep-sea larval biologists don’t get to this point. As far as I know, those individuals that have reared deep-sea invert larvae to a stage that should be competent to settle have been thwarted in their attempts to induce settlement. Maybe the larvae just haven’t seen enough of the world to settle down yet? After all, many deep-sea invert larvae “like us, travel in their youth and see the world, and become stationary like us only in later life.” (Moseley 1880: 546) (2,5).

References and Notes:

1. Prouho, H. 1888. Recherches sur le Dorocidaris papillata et quelques autres échinides de la Méditerranée. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gen. 2: 213-380.

2. Much of the historical information here and the Moseley quote were taken from: Young, C.M. 1994. A tale of two dogmas: the early history of deep-sea reproductive biology. Pp. 1-25 In Reproduction, Larval Biology, and Recruitment of the Deep-Sea Benthos, C.M. Young and K.J. Eckelbarger, eds. Columbia, New York.

3. Young, C. M. and S. B. George. 2000. Larval development of the tropical deep-sea echinoid Aspidodiadema jacobyi: phylogenetic implications. Biol. Bull. 198: 387-395.

4. Pradillon, F., B. Shillito, C. M. Young, and F. Gaill. 2001. Developmental arrest in vent worm embryos. Nature 413: 698-699.

5. Moseley, H.N. 1880. Deep-sea dredgings and life in the deep sea. Nature 21: 543-547, 569-572, 591-593.

It’s ok I am an invert voyeur too! At least you get to do it as a profession!! I’m jealous.

I’m not terribly suprised at #5 though, considering there is still so much for use to figure out about settlement cues for coastal and shelf species, let alone deep sea species with all the unique challenges they add. Of course that’s one of the questions I most interested in.

I should have been more clear on number 4: not all deep-sea larvae feed (some are non-feeding–or lecithotrophic). But, some do feed (called planktotrophic). B. childressi larvae feed. In feeding larvae it is very unclear what they may eat (ie, do they swim to the surface to eat phytoplankton, or do they feed on something at depth?).

Ah ha – so there are other marine invert voyeurs out there!! I’ve had many an evening snuggled up with a few tanks of horny mussels waiting in anticipation for them to release their “goods” – Oh, and all those hours counting larvae – one by bloody one – why do we do it? There’s something special there…. something that I don’t quite think many other souls in this world could ever anticipate as being extraordinary let alone interesting ;P

Sounds like you’re doing some really interesting research – any plans for publications? I’d very much like to have a read – I’m quite interested in NZ’s endemic thermal vent mussel: Bathymodiolus tangaroa