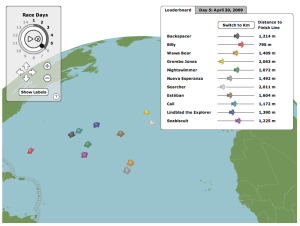

This originally posted here during Megavertabrate Week in 2007. I’m reposting it here in honor of the Great Turtle Race of 2009! Good luck turtles! See map below for updated results – Billy is swimming like crazy!.

——————————————————————————————————–

From The Desk of Zelnio: Dermochelys coriacea

So you walk into the pet shop, you’re looking around at all the little animals and you see a cute little turtle in a freshwater terrarium. You think to yourself “wow, that’s really neat, a cute little turtle.” What you might not realize is that a cousin of this pet store turtle holds some most amazing physiological adaptations for non-fish marine vertebrates, can grow more than 2m (6 1/2ft) long, regularly weigh over 500kg (~1000lbs), and dive deeper than most fully-equipped marine organisms can!

Description Dermochelys coriacea, a.k.a. the Leatherback Sea Turtle, was described originally as Testudo coriacea, meaning “leathery turtle” by Vandelli in 1861 (adopted by Linnaeus 5 years later in his Systema Naturae). Dermochelys, meaning something close to “skinned turtle” (as opposed to shelled perhaps?), was bestowed up the Leatherback by Blainville in 1916. They are the only species in their taxonomic family, the Dermochelyidae. D. coriacea is characterized by its leathery back, absence of scutes (shell plates) and 5 long ridges running from head to tail. The shell is about 4cm thick and composed of an oil-saturated connective tissue. The flippers are proportionally longer than in other sea turtle species, spanning over 2m! That’s basketball player length! The largest specimen on record appears to weigh in at 916kg or 2020lbs (12). Hatchlings can be as small as 50mm (2.4 in.) in length and 50g (just under 2 oz.) and are born mostly black, but covered with tiny white scales that are lost as it grows into an adult.

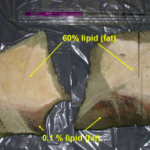

Physiology Heat Conservation: They are able to sustain body temperatures around 25 degrees C when surrounded by water that is 5 degrees C (4). This is helped along by efficient heat conservation system including a low surface area to volume ratio, thick subcutaneous fat layer and countercurrent heat exchangers in the flippers (9). Unusual for a reptile, their resting metabolic rates are 3 times high than in other reptiles, but half as much as mammals when scaled to body size. It is suggested that these turtles can regulate their core temperature by how active they are, more active in the northern latitudes and less active in the tropics (13).

Swimming & Diving: Gravid females top out at around 3m/s (7). Leatherbacks swim more or less continuously at constant speeds and do not take time out to bask in the sunlight (7). They dive in a V pattern and appear to exhibit Diel-Vertical Migration probably following their gelatinous prey as it migrates up and down the water column. Though 95% of all dives less than 200m deep and less than 20 min. long, some dives potentially take a Leatherback to a maximum calculated limit of 1,300m (8). The deepest recorded dive in the literature is 626m and lasted 54 min. though (10). Internesting females have low metabolic rates and are less active, possibly as a mechanism to prevent overheating and to copy with the warmer surface waters of the tropics (15).

Nutrition Leatherbacks appear to exclusively feed on jellies, including medusoid cnidarians, ctenophores and salps (1). Stomach contents from literature include the scyphomedusae of the genera Aurelia, Catostylus, Chrysaora, Cyanea, Pelagia, Rhizostomia, and Stomolophus (1). Hatchlings have also been raised for 6 months on Cassiopea (16) and have been observed feeding throughout the water column on Aurelia, Ctenophores and unidentified gelatinous eggs (14). Amazingly this diet supports not only their growth and metabolic functions, but must maintain their endothermy, which is an expensive process. To keep up a core body temperature and also bring the temperature of their food up to their body temperature requires a lot of jellies, which consequently is considered a low quality food item (1)! This is in part helped by oesophagus lined with conical spines and a compartmentalized stomach (5).

Reproduction Leatherback nesting sites range globally between 40°N and 35°S, but the largest concentration of nesting sites is on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Mating happens while females are on migration to their nesting site and DNA evidence of 1000 hatchlings suggests that these turtles are both polyandrous (one mother, many fathers) and polygynous (one father, many mothers) (3). Females come onto the beach at night to lay eggs. Usually, a female returns to the same nesting beach each season. About 70-80 yolked eggs are laid and incubate in the sandy nest for 55-75 days. A significant portion of nests may be lost to beach erosion, some naturally caused but shoreline development and engineering has played a significant role in recent years. Though there are some egg predators, such as fire ants, raccoons and opossum, egg poaching by humans is very common in many parts of the world. Another threat facing nesting sea turtles is climate change. Sex determination in sea turtles is temperature dependent and lower temperatures tend to masculinize a nest. Old nesting sites could potentially be wiped out by masculinization since it is the females the return to their native nesting grounds (6).

Ecology D. coriacea is a highly migratory sea turtle. Juvenile and post-hatchling habitats are not well known, but adults spend the majority of their life in the open ocean. Lab-reared posthatchlings have been shown to use both chemical and visual aids in foraging behavior (2). The chemical cues may be more important a turtles get older and dive deeper. The leatherbacks are often used by barnacles as a habitat as well and can transport barnacle species across oceans!

Biogeography Leatherbacks are found in all oceans, all over the world in latitudes ranging from subarctic to tropical. They can move quite long distances over the course of a year, even crossing whole oceans. One leatherback was tracked moving over 7,000km in only 124 days (11)! There is low genetic diversity between populations globally, compared to other sea turtle species (6). There is evidence of population subdivision along maternal lineages though, supporting the theory of natal homing (versus social facilitation) in leatherbacks. This is somewhat confounded by the low genetic diversity which may be due to ongoing or periodic gene flow, thus suggesting that the natal homing tendency is weak.

Further Reading:

1. Arai, M. N. 2005. Predation on pelagic coelenterates: a review. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 85:523-536.

2. Constantino, M. A., and M. Salmon. 2003. Role of chemical and visual cues in food recognition by leatherback posthatchlings (Dermochelys coriacea L). Zoology 106:173-181.

3. Crim, J. L., L. D. Spotila, J. R. Spotila, M. O’Connor, R. Reina, C. J. Williams, and F. V. Paladino. 2002. The leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, exhibits both polyandry and polygyny. Molecular Ecology 11:2097-2106.

4. Davenport, J. 1998. Sustaining endothermy on a diet of cold jelly: energetics of the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea. British Herpetological Society Bulletin 67:4-8.

5. Den Hartog, J. C., and M. M. Van Nierop. 1984. A study of the gut contents of six leathery turtles Dermochelys coriacea (Linnaeus) (Reptilia: Testudines: Dermochelyidae) from British waters and from the Netherlands. Zoologische Verhandelingen 209:1-36.

6. Dutton, P. H., B. W. Bowen, D. W. Owens, A. Barragan, and S. K. Davis. 1999. Global phylogeography of the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Journal of Zoology 248:397-409.

7. Eckert, S. A. 2002. Swim speed and movement patterns of gravid leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) at St. Croix, US Virgin Islands. Journal of Experimental Biology 205:3689-3697.

8. Eckert, S. A., K. L. Eckert, P. Ponganis, and G. L. Kooyman. 1989. Diving and foraging behaviour of leatherback sea turtles Dermochelys coriacea. Canadian Journal of Zoology 67:2834-2840.

9. Greer, A. E., J. D. Lazell, and R. M. Wright. 1973. Anatomical evidence for a counter-current heat exchanger in the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Nature 244:181.

10. Hays, G. C., J. D. R. Houghton, C. Isaacs, R. S. King, C. Lloyd, and P. Lovell. 2004. First records of oceanic dive profiles for leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, indicate behavioural plasticity associated with long-distance migration. Animal Behaviour 67:733-743.

11. Hughes, G. R., P. Luschi, R. Mencacci, and F. Papi. 1998. The 7,000-km oceanic journey of a leatherback turtle tracked by satellite. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology & Ecology 229 :209-217.

12. Morgan, P. J. 1989. Presented at the Ninth Annual Conference of Sea Turtle Conservation and Biology, Vero Beach, FL.

13. Paladino, F. V., M. P. O’Connor, and J. R. Spotila. 1990. Metabolism of leatherback turtles, gigantothermy, and thermoregulation of dinosaurs. Nature 344:858-860.

14. Salmon, M., T. T. Jones, and K. W. Horch. 2004. Ontogeny of diving and feeding behavior in juvenile seaturtles: leatherback seaturtles (Dermochelys coriacea L) and green seaturtles (Chelonia mydas L) in the Florida Current. Journal of Herpetology 38:36-43.

15. Wallace, B. P., C. L. Williams, F. V. Paladino, S. J. Morreale, R. T. Lindstrom, and J. R. Spotila. 2005. Bioenergetics and diving activity of internesting leatherback turtles Dermochelys coriacea at Parque Nacional Marino Las Baulas, Costa Rica. Journal of Experimental Biology 208:3873-3884.

16. Witham, R., and C. R. Futch. 1977. Early growth and oceanic survival of pen-reared sea turtles. Herpetologica 33:404-409.

Hatchlings can be 60mm (2 1/2 in.) in length and 5g (100lbs) and…?

Are you sure the hatchlings weigh 100 pounds? Damn!

LOL I made the same mistake 2 years ago when I posted this. I guess I forget to correct it then! Its only one order of magnitude. As my physics professor would say: “Close enough for physics!” (but not for biology lol!)