Two oceans couldn’t be farther apart. The Arctic and Antarctic Oceans have about 160 degrees of separation but Census of Marine Life scientists say they share more than 235 species in common. Most of them are not actively migratory fishes and birds, instead they are passively migratory invertebrates like the sea cucumber and sea butterfly Clione limacina, a swimming snail pictured left.

Two oceans couldn’t be farther apart. The Arctic and Antarctic Oceans have about 160 degrees of separation but Census of Marine Life scientists say they share more than 235 species in common. Most of them are not actively migratory fishes and birds, instead they are passively migratory invertebrates like the sea cucumber and sea butterfly Clione limacina, a swimming snail pictured left.

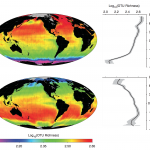

How can two oceans (12,000 km apart) be connected? CoML Chief Scientist Dr. Ron D’Or invokes the global conveyor belt.

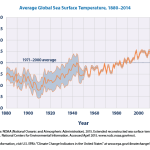

“The deep ocean at the poles falls as low as -1C (30F), but the deep ocean at the equator might not get above 4C (39F).

“There is continuity in the ocean as a result of the major current systems, which we call the ‘conveyor belt’; a lot of these animals have egg and larvae stages that can get transferred in this water.”

There is also the possibility that the “shared species” are superficial.

The traditional approach was to describe an organism’s physical features, so if these organisms lived in very similar habitats, did very similar jobs and ate similar food, then they often looked very alike even if they came from different origins.

Even though organisms look exactly the same and have been identified as being the same type by traditional methods, genetic information can reveal them to be a sub-species or different populations.

This is the International Polar Year. Listen to an interview with Dr. D’Or and read the full story about the bi-polar invertebrata-ta at BBC News. Watch Cliona in action, swimming on a Japanese game show here.

That pesky larval transport and distribution system!

I thought they fixed that already?

Someone really should do something about it, really, first gettin all up in the ships and invading our waters. Spreading those harem worms all around, Now this!

I mean where do our taxes go?!

The final results from DNA will surely be interesting. I have a professor who trashed the conveyor belt theory (very very choleric) but unfortunately never went into details. All he would say is some bad words about some meteorologist who came up wit the idea.

I do, however, have doubts about DNA barcoding. I don’t see it as the method of identification of the future. Reaffirmation perhaps, but good morphology will still need to done. Unless there is an extremely easy, cheap, safe and sure way to scan through a number of regions of DNA and mtDNA. Then, I think we could see morphology slowly being pushed out of the way.

But if my gut feelings are correct, we’ll be lucky if we manage to steal fire from the neighbors.

That’s pretty interesting. I’ve never heard someone trash the conveyor belt. I’ts funny, I’ve always attributed the theory to Wallace Broecker, but I realize now he’s more actually responsible for the idea of a “global shutdown” of North Atlantic overturning, not Meridional Overturning Circulation itself.

When I look at models of the MOC what it seems to be missing is some detail, e.g. tropical downwelling in the West Atlantic, but I’ve never questioned the idea itself. Suppose that would be a healthy thing to do. I find lots of papers criticizing overturning rates, etc.

My experience is that morphology is an important framework and reference for molecular analyses. I hope we can steal some fire, because it seems like morpho taxonomy needs a bail-out!

Indeed, traditional taxonomists are being left behind, since people rarely cite their work. Not having enough citations, they have trouble getting funds for more work and are forced to shut down or work at a minimum, which is usually not enough.

For instance, a very important group of insect called Diptera, have basically no expert in our parts of the wood. Neither do Chironomidae, a very important group for assessing river/lake water quality. All are in need of revision or discovery!

Unfortunately, most of the money goes for various environmental project and charismatic animals (think whale, bear or wolf like) because the of the même. It’s cool to work on those sort of things. Ah, que serra serra.

These guys? Who wouldn’t want to study that?

Probably lots would love to study them, but lots would like to eat as well. Hard to start or support a family on crumbs?

I’m convinced that there’s a lot of people willing to work hard (me being one of them), but as you mention, not enough financial stimulation. In the end, what is know of the fauna is left to the hobby of interested people. And this has its limits – not everyone has a $5000 dissection microscope at home!

I think part of the reason classical taxonomy is so neglected is the failure of its proponents to keep up with the times. As Eric says, finding workers, in theory, isn’t the limiting factor. Its finding the work. It is rare for one to make a living as a morphology based taxonomist these days. While unfortunate, it is the taxonomists who have shot themselves in the foot and are to blame.

For many years, there was a failure to acknowledge or even study the “big” question. Finding and describing new species is exciting and rewarding in and of itself, but students need to develop their taxonomic expertise within the framework of theory and larger scientifically-interesting question. It doesn’t matter what the question is, just that you are working on it and the taxonomy helps you get there. This can be biogeography, biodiversity, dispersal, evolution of habitat use, the list goes on.

Describing species based on morphology and DNA evidence (the way I personally feel is the *right* way to do it under ideal conditions) will have a place for a long time. I always like to think of morphology as a proxy for the suite of genes that encode that character. By looking at several characters you are broadening your scope and ideally approach something closer to the true phylogeny (which can never known). But why look at only the picture when you can easily view the metadata that helped to create that image?

Initially, I was vehemently against DNA barcoding. Karen James can attest to this. But that was become some idiots thought you could do taxonomy based only on sequence information. But barcoding was never developed for taxonomists or to replace them. It was developed as an ecological and forensic tool. We’ve used it to test tuna at our local sushi shop (not tuna, but still delicious) for shits and giggles. In fact, barcoding was developed in part to help alleviate some of the burden on taxonomists. Traditionally, taxonomists at museums were either required to, or did it as part of their job, sort and voucher ID huge amounts of specimens. Barcoding doesn’t replace the taxonomist, but assists the researcher in narrowing down possibilities making it easier for taxonomists and potentially facilitating discovery of news species.

We might have found a new vent shrimp this way. It was barcoded and it came only 94% similar to the species it had been identified as for several years. Now, I will go in and take a closer look and see if I can distinguish morphology or histology.

Thank you Kevin for putting it so eloquently, my thoughts exactly!