News outlets enjoyed a field day last month reporting on the amazing vitality of Porites sp. coral colonies in the South Pacific Bikini Atoll where Americans tested the fifth most powerful atom bomb ever exploded 54 years ago. The Bravo bomb was a 1000 times more powerful than the bomb at Hiroshima. It vaporized three islands, raised water temperatures to 55,000 degrees, rocked islands 200km away and left a crater 2km wide and 73m deep. According to a recent field survey, the crater is filled today with luxuriant coral beds.

News outlets enjoyed a field day last month reporting on the amazing vitality of Porites sp. coral colonies in the South Pacific Bikini Atoll where Americans tested the fifth most powerful atom bomb ever exploded 54 years ago. The Bravo bomb was a 1000 times more powerful than the bomb at Hiroshima. It vaporized three islands, raised water temperatures to 55,000 degrees, rocked islands 200km away and left a crater 2km wide and 73m deep. According to a recent field survey, the crater is filled today with luxuriant coral beds.

Trees of branching Porites coral up to 8m high have been established, creating thriving reef habitat in what should be an atomic wasteland.

Chris Rowan of Highly Allocthonous covered the story with pictures that clearly indicate large and healthy colonies of branching scleractinia. About 50 species of coral previously known from the site were gone from the reef though…

“probably due to the 23 bombs that were exploded there from 1946-58, or the resulting radioactivity … ambient gamma radiation on the residential island of Bikini atoll was fairly low – but when [researcher Maria Beger] put the Geiger counter near a coconut, which accumulates radioactive material from the soil, it went berserk.”

That’s hot. Reef building corals are incredibly resilient. The missing coral species are fragile lagoonal specialists that have yet to recover. But Rick MacPherson of Malaria, Bedbugs, Sea Lice, and Sunsets points out that ecological connectivity played an important role in the rate of the reef recovery. Bikini got lucky. New larvae were likely imported from nearby Rongelap Atoll, a large healthy upstream reef system where atomic testing was not conducted.

One thing missing from the discussion so far is the fact that the radiocarbon signature of wartime aggression and atomic testing in the 1950’s is currently present in the otoliths of fish and the skeletons of shallow and deep-sea corals around the world. Those wartime years left a global footprint on the world’s oceans.

One thing missing from the discussion so far is the fact that the radiocarbon signature of wartime aggression and atomic testing in the 1950’s is currently present in the otoliths of fish and the skeletons of shallow and deep-sea corals around the world. Those wartime years left a global footprint on the world’s oceans.

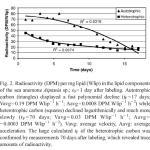

For example, deep sea researcher Brendan Roark of Texas A&M and colleagues collected a bamboo coral from a Northeast Pacific seamount peak 700m deep in the Gulf of Alaska in 2002. The team used laser ablation techniques on a cross section of the coral to identify a Carbon 14 spike in the axis of the skeleton, and then used that benchmark to determine the coral’s age somewhere between 75-125 years old.

It’s amazing, isn’t it, that the Atomic Era left an indelible mark on the world’s oceans, and that science still finds this quite useful. A big question remains. Reef corals can survive a nuclear attack, but will they survive the onset of climate change?