Whale-fall communities are one of the most unique habitats in the deep oceans. When a whale dies and sinks to the ocean floor, it represents a carbon-rich parcel that contrasts sharply to the food-poor desert around. Whale carcasses attract both opportunistic, and typically scavenging, species who feed on anything. In addition, there are a suite of species that are specially adapted to whale carcasses like the bone-eating worms. Whale falls were first discovered in 1989 by Craig Smith and team and just two short years after a fossil whale fall was found. These fossil whale-fall communities, found in Japan and Washington state go back to 40 mya. Interestingly, these whale falls host different mollusc and whale pairings than do recent ones. The bivalves are extinct, the baleen and toothed whales archaic and small.

Given the tremendous size of modern whales associated with whale-fall communities and that fundamentally different bivalves are found in recent communities, lead to speculation that modern whale-fall communities occurred when whales got really big and really oily bones. Enter new and exciting work by Nicholas Pyenson and others that puts this speculation to rest.

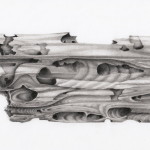

Looking at a very small baleen whale (smaller than a VW bug) fossilized from the Miocene (15-11 mya), Pyenson and colleagues report on 20 small bivalves attached to the skull and skeleton. The whale was excavated over 20 years ago in Ano Nuevo along the central California coast. The whale when on display, with the bivalves unnoticed, at Long Marine Laboratory in Santa Cruz until the lab donated the partially articulated skeleton to the Museum of Paleontology in 2005 when Pyenson noticed the attached clams. They display enough characteristics to place them in the family Vesicomyidae, the same family that contains the species on modern whale falls. Besides the fact that this represents one of the best fossilized and closest association of species to whale skeleton (i.e. they were attached), it completely turns over the previous hypothesis. This study demonstrates that size doesn’t matter, well at least to whale-fall communities. The authors suggest that

this fossil whale likely had really oily bones, and, based on the age of the fossil, we can therefore provide a minimum time for the origin of oil in whale bones. This last point, in a way, is a hypothesis we’re hoping that other people can test in the future.

Nichola Pyenson’s Website on the fossilized whale fall.

Large vertebrates have been dying in the ocean for millions of years. You reckon these communities might have gathered on the carcasses of Tylosaurs or Liopleurodons? Any evidence of plesiosaur- or mosasaur-fall communities in the fossil record?