Bivalves: clams, scallops, oysters, cockles, and mussels, have rich lives and complex evolutionary histories far beyond the deep-fryer. Here are vignettes of four bivalves that provide a small glimpse into their world. So next time you order the frutti di mare linguini, ponder for a second what you are about to eat.

Smart Scallops

Edward ‘Doc’ Ricketts, renown marine biologist and friend to full-time novelist and part-time alcoholic John Steinbeck, once stated: “next to the octopus, the scallop is the ‘cleverest’ of all the mollusks”. While I don’t entirely agree with that remark, I do concur that scallops are perhaps the most interesting of all the bivalves, like these polychromatic Noble Scallops (Mimachlamys nobilis). What makes scallops (Pectinidae) unique among the bivalves are their

baby-blue eyes, ones that would give a Frank Sinatra a run for his money. Surrounding the open-end of the shell in upper and lower rows as a vigilant arcade, these simple peepers can detect changes in light and perceive basic movement, warning the scallop of advancing predators. Their response is to flee by snapping the two sides (valves) of their shell like crazy zombified castanets, scurrying in zig-zagging movements away from the imminent threat by forcing out strong spurts of water every time the shell snaps shut. While these sudden movements may not be guided in a specific direction, the main goal is to get the scallop way from what may hope to eat it, which usually propels them far enough from harm’s way.

Adaptations for this snap-and-zag escape consist of a wide, flexible hinge at the back end of the shell, and a single adductor muscle that can quickly pull the two halves of the shell together. It is this muscle, making about 20% of the soft tissue inside the shell, that one eats as the ‘scallop’ in a seafood platter, with most of the remaining flesh discarded. Most other non-western countries relish the extra innards of the scallop, especially the swollen and succulent gonads during the scallops’ mating season, but those in the more industrialized nations can afford to waste what is perfectly edible. And ironically, while the tasty adductor muscle may be the key in a scallop’s escape from a predator, it doesn’t work so well when trying to flee the path of a 30’ beam trawl dragged along the bottom of the sea.

Boring, Boring, Boring…

Clams can be boring, really boring. No, really, boring. Some species bore into packed mud and some bore into wood or even whale bone, but the Warty-necked Piddock (Chaceia ovoidea) can actually bore into solid rock. Larval piddocks settle into small cracks or existing holes in the rock, and as the shell grows, the posterior portion of the shell develops rows of rough ridges that act as a rasp, and the clam uses it’s muscular foot to bump and grind, literally drilling into the sandstone, shale, and limestone on the ocean floor. As the clam continues to grow in size, it’s burrow becomes an inverted funnel, with the original hole opening to the outside, and a larger interior den that increases in size as the clam’s shell grows and constantly scrapes and remodels the inside of its home. Though it can never escape its clam cave, it lives a simple life of a filter feeding bivalve by extending two large fleshy

siphons out the front door that look like a tunicate. The larger incurrent siphon (the gazin) sucks water and suspended food into the body for filtering, and the smaller excurrent siphon (the gazout) flushes the filtered water outside of the clam’s shell. While their means of feeding isn’t impressive, their bivalve superhero ability to literally drill into solid rock should convince some of you that boring clams certainly aren’t boring. But what about sex? Celibate clams cloistered in a stone cell? Easy, fertilization is external, with males & females releasing sperm and egg simultaneously during particular spring tides.

Motherly Love

For Mother’s Day, we in the Malacology Monday team honor all those mothers out there, present and past. I experienced much too recently the impermanence of one’s mother and the void it leaves in the heart, so perhaps this True Heart Cockle may fill that hole for those of us who have lost their mother. This heart is full of motherly love. The genus name Corculum means ‘darling heart’ in Latin, and the species name cardissa is the Greek word for ‘female heart’. Their family of bivalves is the Cardiidae, meaning ‘heart’ in Greek, and they are a member of the larger taxonomic group Veneroidea, stemming from the Latin venereus, derived from Venus, the goddess of love, which is most likely how you were conceived by mom in the first place. But Corculum cardissa is not like most mothers. The True Heart Cockle is a hermaphrodite, not an uncommon method of reproduction in the invertebrates, but a rare method of producing young among the bivalves. As Corculum expels an egg, it is carried away by the currents and rapidly develops over the next two days into a miniature copy of the mother it will never see again. In the meantime, mother has an adopted family of her own microscopic dinoflagellate algae living in her tissues. Her semi-transparent shell acts as a tiny greenhouse protecting these adoptees who pay their respects by manufacturing food through photosynthesis that supplements what other food particles she strains from seawater through her gills. What she lacks as an absentee mother for her own spawn, she makes up for as the caretaker to hundreds of tiny dinoflagellates.

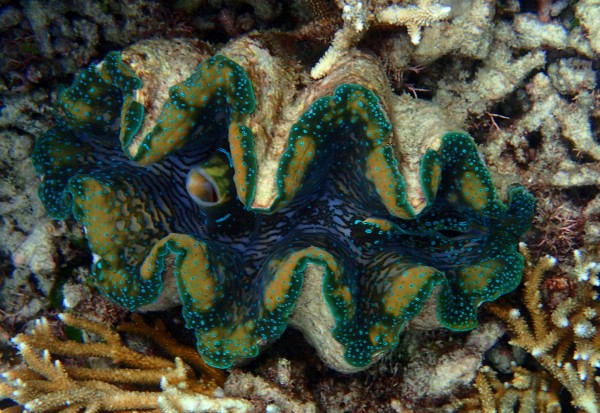

Heavyweight Champion of the Bivalve World

The Malacology Monday team was recently on expedition deep into tropical malacology. The highlight of our explorations along the Great Barrier Reef were dives with the giant clam (Tridacna gigas), from wee ones smaller than an Oreo cookie, to some massive old guardians of the reef that were near record size. This clam is the largest bivalve alive today, with their shell reaching over 1.3 meters (4.2 feet) wide and weighing a whopping 331 kg.(730 lbs). While they are indeed clams, they live more like corals, housing symbiotic photosynthetic zooxanthellae in their large, brightly-colored fleshy mantle, which look like Mick Jagger’s swollen lips after being decked by an enraged Bianca. But these lips, like the mantle of the Heart Cockle (above) house the millions of

tiny algae that convert tropical sunlight into food energy, sharing it with the clam and supplementing the clam’s diet of filtered detritus and plankton to keep it alive. For that reason, these clams must live in the warm and intensely light shallows of the tropics where they can be abundant enough to be the dominant component of some reefs, even exceeding coral in biomass and coverage. While the giant clam population around the Great Barrier Reef appears stable, with even the largest clams seemingly abundant, pollution, sedimentation, dredging, and collecting clams directly for food or sale into the curio trade, giant clams elsewhere are declining or even wiped-out entirely. Australia, however, has been pioneering the aquaculture of giant clams, and have successful long-term projects to re-populate reefs in the South Pacific with these massive mollusks.

This was a great read! Thank you for opening my eyes to the world of clams!

Wow, this was really fascinating! I love the bit about warty-necked piddocks boring into rock; I wish I could put them next to, say, steel or lead, and wait a few hundred thousand generations, and see how strong they can get.

Thanks for writing this, will have to read again later to thoroughly absorb it too!

Awesome!! Thanks you lot!!

Lil cuties doin their briney thing : )

I saw some fine gigantic clam shells uncovered in vanuatu on a hill which were approx 5000 years old and still in good condition!

And then realised a melbourne university I work on had limestone (Miocene I think) 19 million years old & astonishingly fossiliferous- what a legacy for these lil guys!